“The first two weeks out here are the best, because people are full of hope, identifying and projecting who they are as individuals,” said Michael Wells, standing behind his table in front of the 116th Street gates on Broadway. “Who am I? What does my room say about me?”

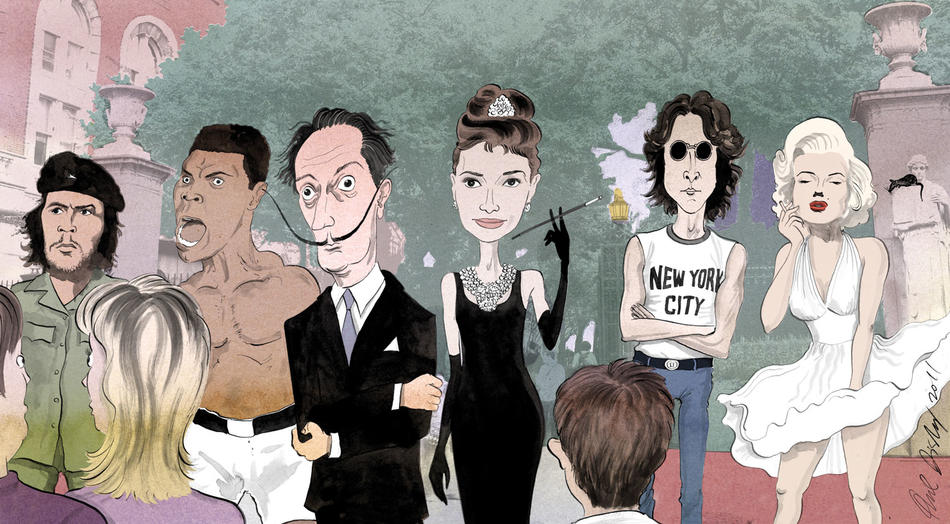

On a sunny, beach-blue day a week before the start of classes, Wells, 53, wearing braids, tan-tinted Ray-Ban sunglasses, and a gray Columbia T-shirt, was helping students answer those perennial questions. Dalí or Ali? Van Gogh or Golightly? Monet or — money?

Wells sells posters. For the past eight years, he has brought pop personality to local apartments and dorm rooms with his stash of Hollywood pinups, famous paintings, Harlem jazz legends, the rock ’n’ roll tragic dead, and arty photographs of couples kissing. For many of his customers, wallpaper means the backdrop of a computer screen, and the sight of 18-year-olds turning over the big laminated leaves of Wells’s folio called to mind the tactile discovery of holding a record album, or a world atlas.

On either side of Wells, under canopies of Chase blue and Citibank white, purveyors of other products and services competed for students’ attention. Time Warner Cable offered high-speed hookups; a yellow booth for Havana Central touted dollar empanadas on Wednesdays and live Latin music all weekend; assertive young bank reps in blue V-neck pullovers hawked credit lines and cash rewards; and by the curb, on its haunches, crouched a 25-foot-tall, red-eyed, inflatable rat.

“Audrey Hepburn,” said Wells, when asked about his biggest sellers. The choice was surprising for a clientele born circa 1993, the year of Hepburn’s death, but as Wells remarked, “I never fail to see a mother or grandmother talking about Audrey Hepburn to a daughter or granddaughter.” (On this day, Audrey, sporting her Breakfast at Tiffany’s pearls, black gloves, and long cigarette holder, was purchased by an undergrad from Russia.) John Lennon, Jimi Hendrix, and Jim Morrison remain popular, said Wells, but “Marilyn Monroe has dipped off. She used to be huge.”

The same could be said of Barack Obama and Lady Gaga, according to Wells. (Earlier that morning, a teacher had bought an Obama poster, which Wells speculated was for classroom use.) Chase and Citibank, on the other hand, were still huge, and every so often a student would stop at one of the brochure-covered tables and fill out forms. Chase proffered lollipops. In the bright-red stall of Sovereign Bank, which was bought in 2009 by Spain’s Banco Santander, and which promised $50 if you applied for a loan, one of the friendly agents cast a wary glance at the towering rat. “What company is that from?” she said.

The rat was in fact a prop deployed by the New York City District Council of Carpenters to protest alleged labor violations involving a subcontractor working on campus. It was the closest thing on the sidewalk to a political statement. The Time Warner guys, 20-year veterans of this back-to-school bazaar, noted there were fewer socialist booths than there used to be (the current figure was zero), though earlier that day a man was handing out a special edition of Revolution, the newspaper of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA. In it were Bible-style excerpts from BAsics, a collection of writings by RCP leader Bob Avakian. (BAsics 3:1: We need a revolution. Anything else, in the final analysis, is bullshit.) Such were the choices on 116th: violent overthrow or free checking with no minimum balance? Audrey or Marilyn? Cubism or Cuba?

Wells had answers. Picasso, for instance, always flew off the rack, but sales of the iconic red-and-black graphic of Che Guevara, the physician-turned-Marxist-guerrilla, had been flagging since 2008. Wells blamed oversaturation. Market forces had put the “Che” in “cliché,” creating a dilemma for the fashion-conscious that no bargain could correct. (All of Wells’s posters cost $12, or the price of Havana Central’s Ultimate Mojito.)

Despite lowered interest in some of his stock, Wells, who is from Harlem, has a better time selling posters at Columbia than he does elsewhere in the city. Etiquette-wise, Wells suggests, Columbians are more Holly Golightly than How to Marry a Millionaire.

“It’s nice,” he said, “when no one tries to haggle.”