Twenty-three thousand architectural drawings. Forty-four thousand photographs. Six hundred manuscripts. Three hundred thousand letters. “It’s a magnitude beyond what anybody can imagine,” says Carole Ann Fabian, director of Columbia’s Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library.

On September 4, the University announced that Avery, in a joint acquisition with the Museum of Modern Art, will receive from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation the entire paper-based archive of America’s essential architect.

Frank Lloyd Wright? At Columbia? Nature-besotted Emersonian, rural Wisconsinite married to the Midwest and the Southwest rather than the Upper West, schemer of horizontal Prairie houses rather than skyscrapers, a radical who declared that cities, one-time agents of culture, now stood in the way of culture, an innovator who bashed American architects for harking back to a European past instead of growing buildings from the native soil (“a building dignified as a tree in the midst of nature”), a man who is reported to have said of the love-triangle murder of Beaux-Arts leader Stanford White of the firm McKim, Mead & White, “Harry K. Thaw killed Stanford White for the wrong reason” — could it really be that the drawings and scribbled-on cocktail napkins of this pioneer of modern design and espouser of “organic architecture” will reside in the vaults below McKim, Mead & White’s Beaux-Arts Avery Library?

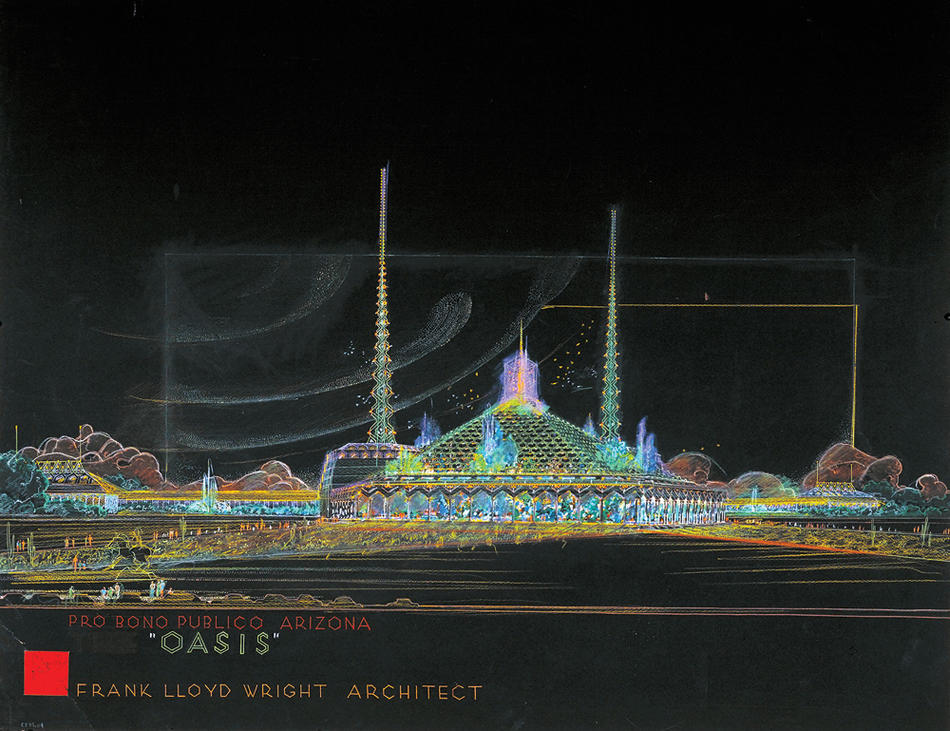

“This was a very serious decision about doing the right thing for a national treasure,” says Fabian. “The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation had a clear idea of its mission to protect the legacy in all its forms.” Under the agreement, the foundation will continue to operate the Wright historic sites of Taliesin (in Spring Green, Wisconsin) and Taliesin West (in Scottsdale, Arizona, where the papers have been kept since Wright’s death in 1959), while MoMA will house Wright’s architectural models. Avery, a world-class library that the foundation judged would provide superior care for the papers and greater access to scholars, will maintain the paper evidence of Wright’s 1,141 projects. “The drawings are works of art,” says Fabian. “You open any drawer and see jaw-dropping beauty.”

Situated amid Avery’s 1.5 million architectural drawings and records and more than 600,000 volumes, Wright’s papers will live alongside the corpus of works of other Americans like Philip Johnson, Greene and Greene, A. J. Davis, and, of course, McKim, Mead & White.

“When you bring Wright to New York, and you put him in a collection like Avery, he’s now in this larger universe of genius — and remains a giant in that universe,” Fabian says. She points out that Wright “has always been a special focus at Avery,” and gives some examples: bookcases containing every significant research volume on Wright; dozens of rare editions of Wright books, including Wright’s own copy of The House Beautiful (what Fabian simply calls “the Book”); blueprints for Wright’s masterpiece Fallingwater and related letters of the Kaufmann family, which commissioned the house (“The Kaufmanns gave papers to Avery decades ago,” says Fabian. “The correspondence between Wright and Edgar Kaufmann will come together here”); preliminary drawings for the Guggenheim Museum; renderings of the Dana House; and Wright’s early drawings under mentor Louis Sullivan. The transfer of the larger archive, to be completed in five years, will make Avery the epicenter of Wright scholarship.

“If you’re a scholar, you’ll be able to see the primary materials — the actual drawings — and the secondary and tertiary literature,” says Fabian. “Treatise, plate volumes, drawings, and critical analyses all come into play here. The scholar visiting Avery will get to move across that entire body of work.”