This spring, before the desert sun gets too strong for delicate onionskin dreams in colored pencil, a crew of art movers will roll up to a lozenge-shaped stone building at Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright’s utopian compound in Scottsdale, Arizona, and load the first shipment of the architect’s paper-based archives into the climate-tuned cargo holds of two unmarked semitrailers. The papers — hundreds of thousands of drawings, sketches, manuscripts, and correspondence — will be driven in their customized crates through a countryside that appears an unchecked expression of a vision Wright described in his 1932 book The Disappearing City. “Imagine spacious landscaped highways ... giant roads, themselves great architecture, pass public service stations, no longer eyesores, expanded to include all kinds of service and comfort.”

On, then, to the highways, leading to a faraway city that has yet to disappear; on to the future of Wright scholarship; on to Avery Library!

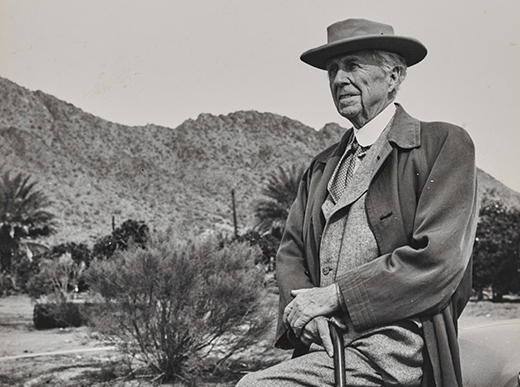

But not too fast: there are potholes on I-40 and memories back in the Sonoran dust. The archive, which Columbia acquired in 2012 as part of an arrangement with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and the Museum of Modern Art (see the news story in the Fall 2012 issue), was directed for more than fifty years by its founder, Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, who in 1949 became an apprentice to Wright and remained with him until the master’s death ten years later.

“Mr. Wright wanted his drawings kept here, but he did not know how much his archive would grow,” says Pfeiffer from his office at Taliesin West. His “Mr. Wright,” spoken in a New England accent unbleached by sixty years in the desert, recalls a scene from Henry James’s The Aspern Papers, in which the narrator, noting the designation used by the ancient inamorata of a long-dead poet, says, “I can’t tell you how that ‘Mr.’ touches me — how it bridges over the gulf of time and brings our hero near to me. You don’t say, ‘Mr.’ Shakespeare.”

Though to be fair, everyone at Taliesin West refers to the architect as Mr. Wright.

“Mr. Wright,” says Pfeiffer, “had a love-hate relationship with New York.”

The architect loved staying at the Plaza, loved being recognized and courted, but skyscrapers and density weren’t his cup of tea. Just three Wright structures can be found in America’s biggest city: the Guggenheim Museum, the Crimson Beech (a prefab house on Staten Island), and, at the corner of East 56th Street and Park Avenue, on the ground floor of someone else’s skyscraper, the Hoffman Auto Showroom. The showroom’s interior was originally designed for car importer Max Hoffman’s Jaguar business, though by the time the space was completed, in 1954, Hoffman had switched to Mercedes-Benz. The automobiliac Wright owned editions from both car makers, as well as a collection of Cadillacs, Bentleys, and Lincolns.

The showroom, still in operation, has a small spiral display ramp that predates the Guggenheim’s giant whorl on Museum Mile. The turntable is mirrored so that “as you look at the car, you’re also seeing underneath the car,” Pfeiffer says. Above the smooth spiral ramp is a round, mirrored ceiling of triangles and curved trapezoids. “Mr. Wright wanted to create a feeling of motion rather than a flat showroom.”

Good tonic for a city whose traffic problem Wright in 1957 called “insoluble.”

Pfeiffer, who has devoted his life to preserving and making available the work of America’s Architect, is saddened by the archive’s transfer, but admits the necessity of providing such a vast, fragile, and precious legacy the most secure and accessible home possible. “It will be safe at Avery,” he says. “Safe into perpetuity.”

The staff at Avery, having spent the previous six months preparing for the arrival of the treasure-stuffed semitrailers — reconfiguring vault space, ordering and installing custom furnishings, testing climatic controls, assembling made-to-order cabinets that can hold drawings that are upward of thirteen feet long — will rehouse and reorganize the archive from April to September, according to Avery Library director Carole Ann Fabian. (On May 20, Avery will offer a sneak preview of the Wright collection as part of its annual display of recent acquisitions.)

At Taliesin West, meanwhile, life will go on, in the subtly prescribed way of the fountainhead’s ideal. The complex began taking shape in 1937 in the foothills of the McDowell Mountains, and became Wright’s winter home as well as an architectural school that is still in operation. Much of the surrounding desert has since filled up with houses, but when the semitrailers, heavy with history, snake down the driveway, their rearview mirrors will frame a lasting vision: desert stone and red beam, buildings low-slung, slanted, cantilevered, ramped, courtyarded, paths and pools, hexagons and triangles, rooms of Wright chairs and Wright lamps and grand pianos, surfaces burnished in Cherokee red, Wright’s signature color.

This was the red of one of Wright’s favorite cars, a 1940 Lincoln Continental. That car, Pfeiffer recalls, had no rear window.

“Mr. Wright said, ‘Well, it’s not where I’ve been that matters. It’s where I’m going that counts.’”