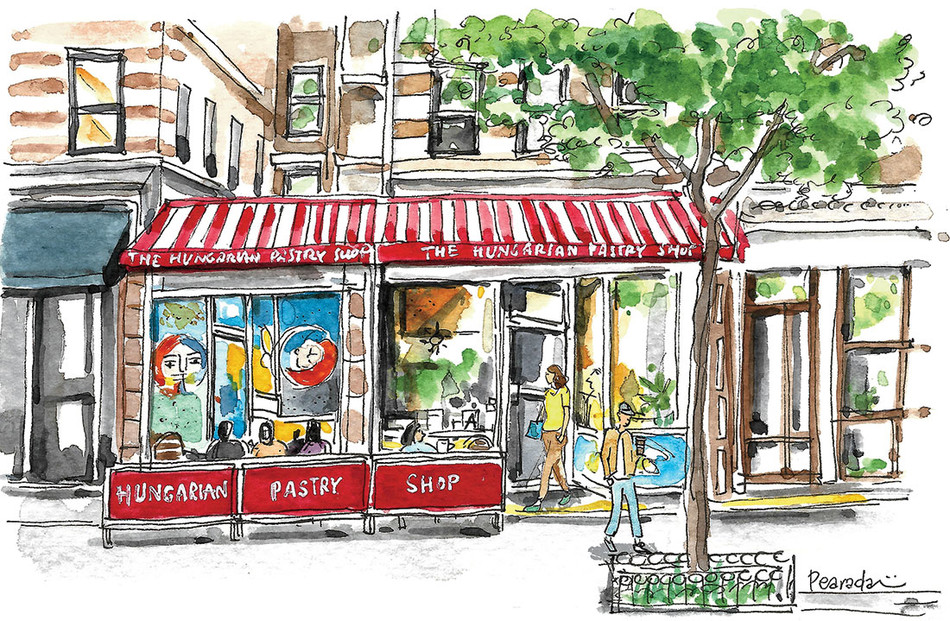

On a recent sunny weekday, the Hungarian Pastry Shop, like the marvelous white peacock in the garden of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine across the street, flaunted its feathers. At the sidewalk tables, gray-haired regulars read newspapers and magazines, students in Columbia T-shirts stared at sticker-plastered laptops or at the pages of canonical novels, and sparrows hopped around in search of crumbs. There were berets and bike helmets, The Trial and Ulysses, bulldogs and poodles. Inside, pies and pastries of lemon, chocolate, and raspberry beckoned from the glass case. At the tables, a woman wiped her eyes as she confided in a friend; a young man read a book on Northern opposition to abolition; and two older, tweedy saxophonists discussed which jazz clubs had reopened.

It was a remarkable juxtaposition with the scene a year earlier, when the sword of COVID-19 hung over every café in town. Back then, Philip Binioris, proprietor of the Hungarian, was facing the grim reality that this cherished spot, social hub and workspace for generations of Columbians, was in danger of fading away as quietly as it had opened nearly sixty years before, when the Columbia Daily Spectator announced the new establishment in a tiny ad on the back page: "Hungarian Pastry Shop, 1030 Amsterdam Ave. (near 111th St.), home baking, coffee, espresso."

It was 1961, and even with its ideal location there was nothing to suggest that the place would outlast nearly all other coffeehouses then in the city. Run by a Hungarian immigrant named Joseph Vekony, the shop, located on the ground floor of a six-story 1910 building facing the garden of St. John’s, quickly drew professors, students, artists, writers, locals, tourists, hospital workers, and, of course, the occasional scruffy café intellectual hunched over an esoteric text.

For reasons unknown, “expresso” replaced “espresso” in the ad copy starting in 1963, and by the early 1970s the blurbs promised “Good Coffee, Good Pastry, Good Atmosphere.” (Spectator food critics have at least agreed about the atmosphere.) In 1976, Vekony sold the business to Binioris’s father, Peter; Theodore Magos, an architect; and artist Yanni Posnakoff. The new owners, all Greek immigrants with high regard for the Hungarian pastry tradition, expanded the seating area and tweaked the ad copy ("Enjoy intellectual stimulation in a joyous ambiance inspired by the timeless qualities of the European tradition"). Posnakoff, a devotee of Greek-Armenian mystic George Gurdjieff, painted eleven angels on the walls inside and out, each paired with a word signifying an attribute of God: honesty, tolerance, gentleness, generosity. Next to the front window rests a painting of a larger angel, with the words Expect a Miracle Today.

Over the years, the Hungarian has become a popular venue for first dates, marriage proposals, breakups, job interviews, scholarly disputes, screenplay collaborations, sketching, scribbling, studying, crosswording, and old-fashioned reading. Philip Binioris, who is thirty-five and grew up around the corner, began working at the shop after school in seventh grade. He remembers when there was a pool table in the basement and how, as a teen, he idolized the Columbia grad students who came there to play. By the time he took over the business, in 2012, he was sensitive to the blend of ingredients that make for a welcoming milieu. “I had so many wonderful memories of the place — and so many loyal and valuable customers had such wonderful memories — that my biggest plan was to not mess it up,” he says.

This meant continuing the policy of no music, no Wi-Fi, no outlets, dim lighting, and free coffee refills, as well as preserving the menu, the recipes, and the angels. The clientele, too, remained constant: the retired social worker who met his first boyfriend at the Hungarian in 1978 or the St. John’s gardener who first visited the shop in 1969 (“There were a lot of elderly men playing chess,” she recalls). Writer Jay Neugeboren ’59CC, who lives nearby, was there at the beginning. “It was like a sixties coffeehouse without the folk singing,” he says. “It has not changed much at all.”

One of the few evolving features of the Hungarian under the younger Binioris’s management has been playing out on the front walls, which boast framed dust jackets of books written in part at the shop’s small tables — titles by Nathan Englander, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Julie Otsuka ’99SOA, Rivka Galchen ’06SOA, and many others.

“My dad and his partners did an amazing job bringing people in — making connections beyond the counter and really just being part of a community,” says Binioris. “There’s no pretense to the place. It’s just here. We open the door and hope that people come in, and we try to take care of them.”

That care was reciprocated during the bleakest days of the lockdown, when people showed up to get their strudel and tortes to go, waiting in lines that stretched around the corner. “During the pandemic I realized the value of that relationship more and more,” says Binioris. “It’s not just a cup of coffee and a pastry. There’s a human relationship, and that’s really a beautiful thing.”

This article appears in the Fall 2021 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Strudel for the People."