President Barack Obama ’83CC stood on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, and defined his vision for America. He had sung the melody before, but on this day, March 7, 2015, fifty years after police attacked a peaceful civil-rights march at the site, Obama embellished on the theme and made it opera. Quoting Baldwin, Emerson, and Whitman, evoking Sojourner Truth and Martin Luther King Jr., Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the president paid tribute to the “ordinary Americans” who were willing to face “the chastening rod” and “the trampling hoof” to ensure that America lived up to its promise.

“What could more profoundly vindicate the idea of America,” Obama said, “than plain and humble people … coming together to shape their country’s course?”

Obama’s words touched the vault of American ideals and dug deep down to grassroots. “The single most powerful word in our democracy is the word ‘we.’ We the people. We shall overcome. Yes we can. It is owned by no one. It belongs to everyone. Oh, what a glorious task we are given to continually try to improve this great nation of ours.”

For David Simas, this speech holds the key to understanding the Obama presidency. Simas, the CEO of the Obama Foundation, a nonpartisan nonprofit that sponsors civic leadership programs and is overseeing the creation of the Obama Presidential Center, says the philosophy of the forty-fourth president — his belief in the possibilities of democracy — can be detected in every stage of his political career. In his post-Columbia years, when he worked as a community organizer in poor neighborhoods of Chicago and would sit for hours in people’s homes, asking them about their lives; in his remarks in Athens in the last year of his presidency venerating the idea of demokratia (“Kratos — the power, the right to rule — comes from demos — the people”); in his postpresidential investment in the Obama Foundation Scholars Program at Columbia, which develops the problem-solving skills of young leaders from around the world, Obama has always encouraged people to use their power as citizens to make government work for them. So when it came time for the foundation to produce an official oral history of the administration — something that has been done for every president starting with Herbert Hoover — it seemed essential to go beyond the standard recollections of cabinet members and legislators. “It’s important to reach into the lives of people who were touched in one way or another by the Obama presidency,” says Simas. “Only by getting the full expanse — from senior officials to midlevel and low-level staffers to ordinary people — can you truly tell this story.”

In May, the Obama Foundation announced that it had selected the Columbia Center for Oral History Research (CCOHR) to tell that story. The match seems propitious: Obama is an alumnus with a keen interest in storytelling, and Columbia is the birthplace of the field of oral history. But what most attracted the Obama team was the Columbia program’s breadth, covering corporate leaders and organizations as well as activist movements and citizens. “We were impressed by Columbia’s experience at capturing this diversity, which we thought would be critical to the project,” says Simas.

The Obama Presidency Oral History Project is led by sociology professor Peter Bearman, director of the Interdisciplinary Center for Innovative Theory and Empirics (INCITE), which houses CCOHR. He will work with Mary Marshall Clark, director of CCOHR, and Kimberly Springer, curator of the oral-history collection at Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Expected to take five years to complete, the project will include hundreds of audio and video interviews as well as a profile of First Lady Michelle Obama and interviews collected by the University of Hawaii and the University of Chicago on the early lives of the Obamas. Transcripts will be posted online, and audio and visual files and paper transcripts will be publicly available in Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Of the four hundred people to be interviewed, about a quarter will be everyday Americans. The project will feature the principal actors around the president and also bring out the individual voices of the chorus. It will be a portrait not just of a president but also of a country.

Oral historians are explorers of the unmapped spaces in the historical record. Collectors of stories and interpreters of memory, they are both discoverers of the past and messengers to the future. Clark and Bearman came to the discipline through different paths. Clark studied liberation theology at Union Theological Seminary. In 1990 she joined Columbia’s Oral History Research Office (as it was known then), and in June of 2001 she became director. Bearman taught sociology and became known for his analysis of adolescent behavior and social networks. The two first collaborated on the September 11, 2001, Oral History Project. In the immediate aftermath of the attacks in Lower Manhattan, Clark wanted to go out into the field but needed help to quickly organize such a big project. She called on Bearman, and together they trained thirty interviewers, who then fanned out over the city, speaking with eyewitnesses, first responders, Muslims, artists, survivors, and other New Yorkers, getting their stories before official narratives took hold.

In 2016, Clark and Bearman began thinking about a new, large-scale oral history, one that would embrace a broad cross section of American life. Inspired by the Depression-era Federal Writers’ Project, which hired unemployed writers to collect the narratives of ex-slaves and others whose voices were underrepresented in the National Archives, they wrote a grant proposal and sent it to the Obama Foundation, hoping for funding. “We had a series of interesting conversations with them,” says Bearman. “Then the election happened.” The conversations stopped, and that project was shelved. But in 2018, as the foundation was thinking about a presidential oral history, the talks resumed. “The foundation had been on its own journey, trying to figure out how to do a real oral history that was different from past ones,” Bearman says. “So we thought, ‘Oh, wow, somehow these roads have intersected.’”

Along with Bearman, Clark, and Springer, the Columbia team includes Michael Falco ’13SIPA, associate director of INCITE, and Terrell Frazier, a doctoral student in sociology and the project’s lead interviewer. The team will consult with a sixteen-member advisory board of prominent historians, sociologists, literary scholars, and journalists chaired by University President Lee C. Bollinger.

“It’s a very interesting and carefully curated board, with a rich distribution of life experiences and academic disciplines,” says Bearman. “Their job is to help us see things that we don’t see. This is a really big and complicated project. Nobody’s ever tried to do anything on this scale.”

The practice of oral history — interviewing people to preserve, as Clark says, “memory, experience, and shifting values” — was established as an organized discipline in 1948, when journalist and historian Allan Nevins ’60HON founded the Oral History Research Office at Columbia. Nevins, who subscribed to the great-man theory — the idea that exceptional leaders drive history — lamented that telephone conversations were replacing personal letters, diaries, and memos. Without these contemporaneous records of leaders’ unvarnished opinions, historians would no longer be able to tell the inside story of events as they happened. And so he interviewed policymakers, business leaders, publishing moguls, and philanthropists, eliciting information that he felt might be of value to posterity. Though his history-department colleagues cast a skeptical eye, seeing oral history as factually unreliable, Nevins’s archive grew, and so did the field.

In the 1960s and ’70s, Columbia’s oral-history office, in partnership with the Eisenhower Presidential Library, conducted the oral history of the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration. (Eisenhower, as president of Columbia from 1948 to 1953, had green-lighted Nevins’s oral-history center.) The Eisenhower project was not the first of its kind. The presidential oral-history genre began in 1960, under the auspices of the Harry S. Truman Library. (Though Hoover and FDR preceded Truman as president, their oral histories were done after Truman’s.)

The standard presidential oral history consists of hundreds of hours of audio recordings and thousands of pages of transcriptions. By documenting a presidency through the recollections of cabinet secretaries and labor leaders, senators and speechwriters, attorneys general and ambassadors, the presidential oral history provides elaborate details and rich insider anecdote. The interviews can corroborate, contradict, or contextualize other records, illuminate a president’s character, and reveal how decisions are made at the highest levels.

In the John F. Kennedy oral history, George Ball, undersecretary of state, comments on the late president’s grasp of international economic policy (“He was very quick. But on a great number of things, I must say, I didn’t think he was ever terribly profound”); in Lyndon B. Johnson’s, Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall sheds light on presidential decision-making (“Mrs. Johnson had a great deal of influence with her husband”); and in Bill Clinton’s, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright ’68SIPA, ’76GSAS, ’95HON reflects on the mystique of the office (“There truly is such power in the office of the presidency that in many ways you imbue the person who is the president with all kinds of things that may or may not be true of that particular personality”).

Of course, a two-term, history-making presidency like Obama’s, which lasted from January 2009 to January 2017, offers countless avenues of inquiry, starting with its improbability. In 2004, Obama became just the third Black senator since Reconstruction. In US history there had been only four Black governors, but Barack Hussein Obama, a name that did not portend electoral success, ran for president of all fifty states and won. He inherited two wars and the worst economic collapse since the Great Depression and presided over a litany of pivotal events: marriage equality (“justice that arrives like a thunderbolt,” Obama called it) and the auto-industry bailout; mass shootings at an African Methodist Episcopal church in Charleston, a gay nightclub in Orlando, and two first-grade classrooms in Newtown, Connecticut (what Obama later described as the worst day of his presidency); the Paris climate accord and the Iran nuclear deal; police violence against African-Americans and the administration’s response. There is, as Columbia journalism professor Jelani Cobb says, “so much that we would want to know more about.”

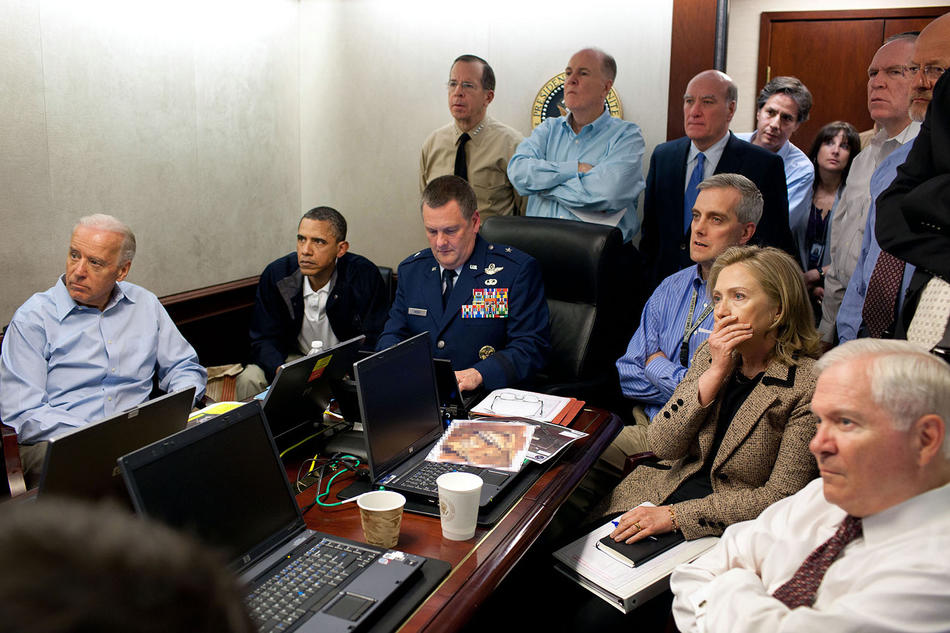

Cobb, author of The Substance of Hope, an incisive study of Obama’s 2008 campaign and the nuances of generational Black politics, is on the Obama project’s advisory board. When asked what topics he’d like the oral history to explore, Cobb reels them off: “What were the strategic considerations of the health-care fight? What were the internal discussions about the mission that killed Osama bin Laden? What was the evolution of America’s foreign policy toward Russia? There’s a lot on Obama’s foreign policy that we haven’t discussed in great detail. An interesting area would be his relationship with Africa and the policy priorities there. And his relationship with the Congressional Black Caucus — people pushing him on matters where they felt he was too moderate.”

Cobb expects that the Obama presidency, under the analysis of oral history, will be clarified in ways we can’t predict.

“We’re looking at this extraordinary event, this presidency, from a distance,” he says. “We’re anchored just offshore, and we see the coastline. But we have no idea what happens once we get inland. There’s a whole other landscape. We don’t even know what we don’t know. Someone may casually mention something in an interview that totally changes our understanding of what happened.”

Early in his presidency, Obama invited nine distinguished presidential historians to dinner. The new president wanted to hear from experts about the institution he now personified. One of the historians was Robert Dallek ’64GSAS, a Bancroft Prize–winning historian and the author of biographies on FDR, JFK, and LBJ.

“President Obama was very interested in learning,” says Dallek, who also sits on the Obama project’s advisory board. “He wanted to hear from us going back as far as Woodrow Wilson and FDR. We ended up meeting eight times. I don’t know how much we taught him — I think he already knew an awful lot.”

“For President and Mrs. Obama,” says Simas, “those dinners were not just an exercise in having historians come in and say what happened. It was, ‘What were people thinking, what were the tensions, what were the hopes, the fears, the power dynamics, the alliances? How did people think through their decisions?’”

The multifaceted, 360-degree, reflective nature of oral history has found a kindred subject in Obama. “Whenever we’d deal with an issue, President Obama would always ask us to take the long view,” says Simas, who worked as an assistant on political strategy and outreach in the Obama White House and was privy to many discussions. “If we were talking about health care, he would say, ‘As you’re thinking about the solution, don’t just give me a range of options that envision what this looks like in a year or two years but what this looks like in thirty, forty, or fifty years.’ That was the perspective he would force us to take. He would then say, ‘Let’s also understand that we’re not the first people to go through this. So let’s have a deep understanding of people who have tackled this in the past. What did they learn? What were the dynamics they confronted?’

“This is the strength of history from the Obamas’ standpoint. It allows you to take the longer view.”

Oral history takes the long view — oral historians are mindful of obtaining information that they imagine will be of interest in fifty years — but it also drills down deep into its subject. Before interviewers go out in the field, they do “extensive, expansive, in-depth research,” says Clark. They must have a grasp of the cultural, social, and historical milieus of the people they’re interviewing and, in many cases, a command of specialized knowledge. The research takes months. “We learn as much as possible so that we can have a conversation that will sustain people’s interest and cause them to ask themselves questions they’ve never asked before,” Clark says. “The goal of oral history is to find something new — to evoke a fresh thought or realization. That is a thrill.”

The interviews themselves are a deftly controlled pas de deux between interviewer and “narrator,” as oral historians call an interviewee. Interviewers must have a lively curiosity and an ability to listen and be sensitive to any signs that flicker across a narrator’s face, voice, or body. “Observation is key,” says Clark. “I try to accommodate people when they seem like they’re shutting down or don’t want as much closeness. It’s a deep encounter. It’s also respectful. We’re not invasive or intrusive, but we do ask hard questions. As interviewers, we must have the ability to identify with that other person, but we must also refrain from complete identification so we can ask the critical questions.”

Terrell Frazier, who joined Clark’s team in 2011 as director of outreach and education, will be heading up a core group of interviewers that can be supplemented as needed through Columbia’s nationwide network of oral historians. The Obama Foundation will then help Frazier connect with Obama White House alumni as well as people outside government who have interacted with the president.

“We’ll want to speak with people who wrote the president letters, people he encountered in his travels, people whose lives he touched in a tangible way — someone who got treated for a preexisting condition under the Affordable Care Act or someone whose sentence he commuted,” says Frazier, who, like the young Obama, worked after college as a community activist and listened to people’s stories. Frazier believes that stories connect people by offering windows into different life experiences. “We’ll ask the narrators about who they are and look at the ways that their narratives came to intersect with the president’s. We want to know the impact that those experiences had on them and on people around them.”

The Columbia team will use a one- or two-person crew and go wherever narrators are most comfortable, which usually means their living rooms. Putting the narrator at ease is job one, and Clark stresses that crew members’ interpersonal skills are as important as their technical ones. “I often take people out to lunch with the crew before a shoot, to bring in a sense of warmth and intimacy,” says Clark. “That’s the oral-history way. We won’t get a good interview if the narrator isn’t comfortable. So we’ll do everything we can.”

Once the recording equipment is set up, the interviewer and the narrator will sit facing each other. Interviews take between one and a half and two hours, with additional sessions held for narrators with longer tenure in the administration. “In oral-history interviews, you’re asked about where you grew up and how your experiences shaped you and led you to where you are,” says Frazier. “If you’re a policymaker, that can be jarring, but in a good way — you thought you were going to talk about a piece of legislation or an interaction you had with the president, and now you’re removed from what you’d prepared in your head and you start thinking about your interactions differently.”

Ronald Grele, who directed Columbia’s oral-history program from 1982 to 2001, was an interviewer for the John F. Kennedy presidential oral history, which began a few months after the president’s death in 1963. By the late sixties, oral historians had shifted their interest from “great men” to the dispossessed, and from facts to the more subjective elements of people’s testimony: not just what people did, but how they interpreted what they did. But as Grele points out, the presidential oral history kept its tie on and avoided introspection.

“Those old oral histories start out with, ‘When did you first meet John Kennedy?’” Grele says. “As if these people had no life prior to meeting John Kennedy. ‘What did you do in the State Department?’ It was like an exit interview.

“With the traditional model, you don’t find out who people are. Clark and Bearman will find out who people are.”

The Obama Presidency Oral History Project is also groundbreaking for its inclusion of Michelle Obama, who redefined the office of First Lady and in many ways set the tone for the Obama presidency.

“As First Lady, you never felt she was an untouchable queen,” says advisory-board member Farah Jasmine Griffin, a professor of English and comparative literature and chair of the African American and African Diaspora Studies Department at Columbia. “We’ve had brilliant First Ladies, but Michelle Obama made you feel you had access: Let’s open up this White House and bring people in. Let’s have this garden. Let’s visit schools. It was a model of a way of being in the world in which one could have fun but still be committed to hard work. It showed girls that they could be glamorous and funny, athletic and smart, that they could know popular culture and high culture. The collapsing of those binaries was something for all children and young people to aspire to.”

Cobb notes that while the symbolic importance of Michelle Obama can hardly be overestimated, her role in Obama’s election was also crucial. “I saw this firsthand in South Carolina in 2008, during the primaries,” Cobb says. “Early on, I talked with a guy who was canvassing, and he said that they encountered a problem, which was that Black voters had never heard of Barack Obama. Then, over time, they began to hear about Barack Obama, but they didn’t know he was Black. So the campaign started putting out his picture. Then, seeing he was Black, people said, ‘What kind of name is Barack Obama? Who is this guy?’ The campaign responded by putting Michelle on the images with him.

“Obama’s background — biracial, growing up in Hawaii and Indonesia — was particularly exotic and not very legible to voters. What was legible to voters was Michelle Robinson. She is identifiably African-American, South Side of Chicago — everyone knew someone like her growing up. As Obama tried to make his political inroads — certainly with Black Americans and possibly with other constituencies — Michelle Obama was really a passport.”

In the open-minded, dissent-brooking spirit of its namesake, the Obama Presidency Oral History Project will be many things, but it will not be hagiography. “We’ll definitely interview critics,” says Clark. “Because in the end, we’re researchers. We want to know how people think.”

Griffin agrees — “I think a good legacy, a strong legacy, can withstand the voices of critics” — but adds that she’d also love for there to be some sense of the pure joy that many citizens felt the night of the first election. Griffin won’t ever forget November 4, 2008. That evening, she took her mother, who was in her early eighties, to an election watch party at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. She recalls the roller coaster of feelings as the returns came in. “Everyone in that audience had given something to the campaign or volunteered, everyone was invested, and I think we were all prepared for it not to happen. Then when Ohio came through, we were like, ‘Really?’

“Later I saw a photograph of the audience inside the Schomburg. It must have been taken when they declared Obama the winner — there was this look of disbelief on people’s faces. Utter disbelief that this had happened. I remember that week so clearly because there was dancing in the streets, and even the next day everyone seemed giddy in New York. People were friendlier to each other. People you never spoke to actually stopped and said hello. I’m so glad my mother lived to see it.”

As the interviews for the Obama Presidency Oral History Project are completed, they will be transcribed and edited, and narrators will have an opportunity to make any clarifications or deletions. Oral-history collection curator Kimberly Springer and archivist David Olson will receive the finished materials, catalog them, and make them available to researchers. “Our priority has always been patron access and preservation,” says Springer — good news for the next generation of historical researchers, and for future ones.

“Imagine thirty or forty years from now,” says Simas. “Imagine a president sitting in that office behind that desk, thinking about a choice she or he has to make; then imagine young organizers on the South Side of Chicago, or in rural Kentucky, thinking about how to make their communities better. Isn’t it possible that by giving them insight into the way President Obama and the people around him and the people in the nation at that time confronted things, how they thought about them, and the choices they made — isn’t it possible that they can learn from that and make better-informed choices themselves? Wouldn’t it be an amazing thing for generations of leaders, whether they’re government leaders or business leaders or ordinary citizens, to have instantaneous access to the archive, the record, the story?

“Just as President and Mrs. Obama looked to history to give them that sense of why people made the decisions they made,” says Simas, “so this oral history will be not just a chronicle of the past but a road map for change in the future.”

The Obama oral history will be one of the crown jewels of Columbia’s oral-history collection, which already contains more than eleven thousand recorded interviews and twenty-five thousand hours’ worth of transcripts. The fruit of seven decades of research and acquisitions, the collection covers a panoply of subjects: radio pioneers, Republican China, the psychoanalytic movement, Black journalists, the Apollo Theater, student movements, Guantánamo Bay and human-rights law, the artist Robert Rauschenberg. There is even an interview with Georgia congressman John Lewis ’97HON. Lewis was at the front of the six-hundred-strong voting-rights march that winter day in Selma in 1965. As the young chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, he had stood motionless as a phalanx of Alabama troopers approached. With news cameras rolling, the police attacked the marchers with truncheons, whips, and tear gas, and Lewis suffered a fractured skull. Fifty years later, Representative Lewis stood at the bridge with the president of the United States, who sang of America and the power of ‘we.’

For Mary Marshall Clark, the Obama Presidency Oral History Project is important not only as presidential history but as a document of American life.

“Obama created a unique public memory,” Clark says. “I think that memory should be substantiated through this project. We should bring back and make public that memory — what it was like for so many people. That memory belongs to the American people, and we have a right to keep it.”