“The paranoid spokesman sees the fate of conspiracy in apocalyptic terms — he traffics in the birth and death of whole worlds, whole political orders, whole systems of human values. He is always manning the barricades of civilization.”

— Richard Hofstadter, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” 1964

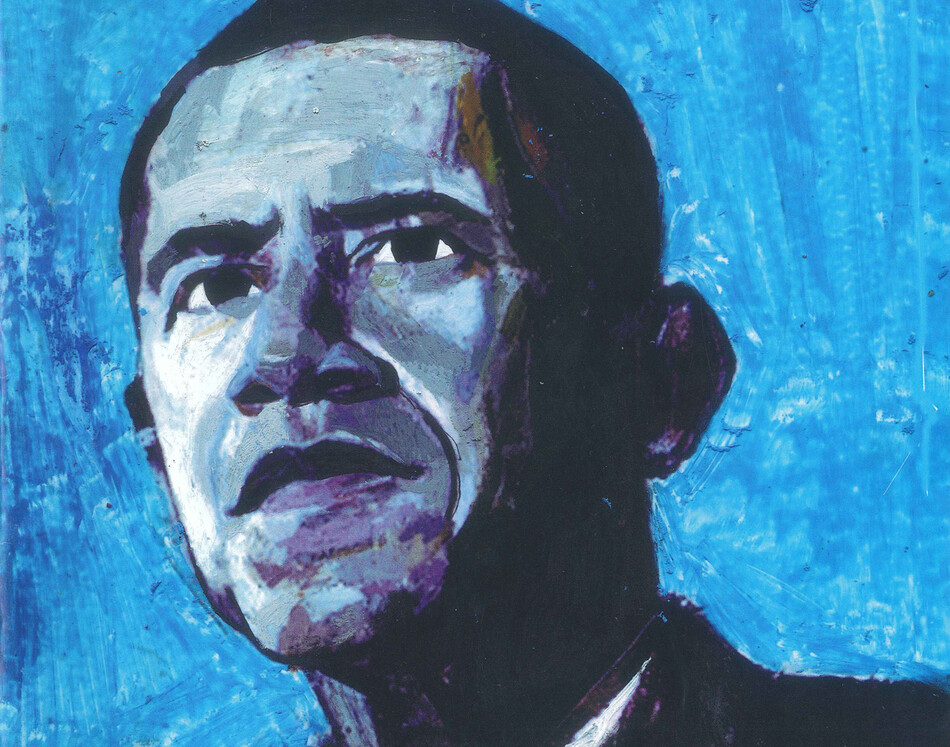

On October 17, 2008, Michele Bachmann, Republican congresswoman of Minnesota, told MSNBC’s Chris Matthews that she was “very concerned” that Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama “may have anti-American views,” and suggested that the American media “take a great look at the views of the people in Congress and find out, are they pro-America or anti-America?” The next day, Rep. Robin Hayes (R-NC), warming up a John McCain event in North Carolina, said that “liberals hate real Americans that work and accomplish and achieve and believe in God,” remarks that harmonized with vice presidential aspirant Sarah Palin’s statement two days earlier, also in North Carolina, that she liked visiting “pro-America” parts of the country. (She also accused Obama of “palling around with terrorists,” a reference to Obama’s acquaintance with University of Illinois professor William Ayers ’87TC, who in 1970 cofounded the Weather Underground.) Then, less than a week after Americans elected Barack Hussein Obama ’83CC as their 44th president, another congressman, Paul Broun of Georgia, told the Associated Press that “as a peace-loving, freedom-loving American citizen,” he was “extremely fearful” that the president-elect was promoting a “philosophy of radical socialism or Marxism.”

These examples are a fair representation of the mindset that Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Richard Hofstadter ’42GSAS illuminated over 40 years ago in his influential essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” Hofstadter, who taught at Columbia from 1946 until his death at 54 in 1970, combined a masterful prose style with an acute critical perception of American political life. He was a member of the Communist Party for four disillusioning months in 1938, became a postwar liberal, and, as an ensconced New York intellectual, exemplified the rise of ethnic cosmopolitanism against an Anglo-Saxon agrarian tradition in decline. With a stiletto pen sharpened by the excesses of McCarthyism, Hofstadter traced a pattern of folk movements in American history that were “overheated, oversuspicious, overaggressive, grandiose, and apocalyptic in expression,” from the anti-Masonic and anti-Catholic campaigns of the 19th century to the McCarthy and Goldwater crusades of the 1950s and ’60s.

“I choose American history to illustrate the paranoid style because I happen to be an Americanist,” Hofstadter states, acknowledging that no country or political party has a monopoly on “the gift for paranoid improvisation.”

Noting that political movements often gain leverage from “the animosities and passions of a small minority,” Hofstadter drew a cutting psychological portrait of his bête noir: the angry, dispossessed rural conservative for whom “the feeling of persecution is central,” and who, unlike a clinical paranoiac, perceives a conspiracy directed not against himself personally but “against a nation, a culture, a way of life."

During the campaign of 2008, one of the most telling charges leveled at Barack Obama on blogs and cable news shows was that he was a covert Muslim. A low point came in March, when Rep. Steve King (R-IA), in a radio interview, contemplated the response of al-Qaeda terrorists to Obama’s name. “His middle name does matter,” King said. “They will be dancing in the streets because of his middle name. They will be dancing in the streets because of who his father was.” Here was the paranoid style in full feather: the linking of Obama to a scheming international “them” that threatens Judeo-Christian culture in general, and the United States in particular. The accusation was, of course, far more offensive to Muslims than it could ever be to Obama, and most Americans rejected it.

So what does this mean for our way of doing politics? For though the paranoid style is a reliable attention grabber, as a political strategy it’s been known to backfire. Barry Goldwater received only 52 electoral votes in the 1964 election to incumbent Lyndon Johnson’s 486, and in 2008, Goldwater’s successor in the Senate, John McCain of Arizona, was beaten by what would have seemed, not so long ago in our post–9/11 world, the most unlikely candidate imaginable: an urbane, worldly, African American Democrat whose middle and last names evoked America’s two most-dreaded enemies. Yet Obama, appealing to what Lincoln, in his first inaugural address, called “the better angels of our nature,” more than doubled McCain in electoral votes, 365 to 173.

“I don’t know if Obama’s election signals the end of the paranoid style as much as it signals at least the temporary muting of the conservative rhetoric and attack mode,” says Robert Dallek ’64GSAS, a leading presidential historian who was a student of Hofstadter. “The kind of stuff that Palin and McCain used, which is part of the paranoid nonsense — that Obama’s not a real American — has been forced to the side now, but not entirely. It’s not gone. It never goes away.”

The paranoid style thrived in the recent era of color-coded terror alerts, finding its voice in right-wing groups that saw America imperiled by illegal immigrants and Islamic fundamentalists, and in left-wing theories about government involvement in the September 11 attacks.

“What distinguishes the paranoid style,” Hofstadter wrote, “is not the absence of verifiable facts (though it is occasionally true that in his extravagant passion for facts the paranoid occasionally manufactures them), but rather the curious leap in imagination that is always made at some critical point in the recital of events.” He adds: “Nothing entirely prevents a sound program or issue from being advocated in the paranoid style, and it is admittedly impossible to settle the merits of an argument because we think we hear in its presentation the characteristic paranoid accents.”

The paranoid advocate doesn’t so much invent wild ideas, then, as undermine sound ones, alienating people with his exaggerations and ultimately discrediting his cause.

“I don’t believe in the paranoid style as an enduring and important part of the American political culture,” says Alan Brinkley, provost and Allan Nevins Professor of History at Columbia. “It’s a style that people adopt, usually in times of stress, and is probably a far less widespread phenomenon than Hofstadter liked to believe. I think the problem with Hofstadter is that he was attributing it to a much larger group of people than actually really did exhibit these characteristics. Just as McCarthy exaggerated the menace of communism, the opponents of McCarthy exaggerated the popular menace that McCarthy had created. And I think the same thing happened in this campaign: there were far fewer people who believed the crazy accusations against Obama than it sometimes seemed.”

Racial Paranoia

The reaction to the New Yorker cover of July 21, 2008, which depicts Barack Obama as a robed Muslim and his wife, Michelle, as an armed Black Power militant, bumping fists while the American flag burns in the Oval Office fireplace under a portrait of Osama bin Laden, underscores Brinkley’s notion about the true dimensions of the paranoid style. To many, the cartoon, titled “The Politics of Fear,” was seen as offensive, insulting, and, not least, damaging to the Obama campaign. But the problem wasn’t that people didn’t understand the magazine’s attempt to satirize certain prejudices against Obama; it was that the New Yorker protested too much. If there were individuals out there who really believed such tripe, the logic went, then surely they could not have amounted to more than a small lunatic fringe, which made the inflammatory image seem more like a projection of the New Yorker’s fantasies about the hinterland (or even about the Obamas) than incisive social commentary. Others praised the magazine for exposing the absurdity of the anti-Obama distortions — and for having a sense of humor.

In his book Racial Paranoia (Basic Books, 2007), which trades Hofstadter’s knife work for compassionate inquiry, anthropologist John L. Jackson, Jr. ’00GSAS argues that as overt expressions of racism have been shamed from the public square, racist sentiment has gone underground, deep into people’s hearts instead of on their sleeves. This makes it difficult, even impossible, for African Americans to know exactly what non-blacks are thinking or feeling behind the smiles, a condition that can turn even blatant satire into something opaque and ambiguous.

But far from easing people’s anxieties about race, the election of Obama, which Jackson regards as “a testimony to the possibility of America truly forging a multiracial and multiethnic society,” has created a whole other set of concerns.

“The new paranoia that we’re going to see among African Americans is this ratcheted-up fear for Obama’s safety,” says Jackson, a professor of anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. “And also a fear about the extent to which he might potentially be scapegoated for the rest of what happens in America. It’s a different kind of paranoia, one that says, ‘Maybe this is all a setup.’” But Jackson is quick to point out the underlying psychic negotiations that make such worries bearable. “People are very self-conscious about how potentially debilitating such a position can be,” he says, “and they don’t want it to define their sense of how they’re going to respond to Obama’s presidency. They can be honest about what’s possible, and how quickly things can go south, but at the same time they want to push it aside and move forward and be positive.”

Knowns and Unknowns

“The fact of Obama’s election when you look at recent American history is quite startling,” says Brinkley. “Not only because he’s African American, but because of the character of his campaign. It wasn’t radical by any means, but it was different from most campaigns in that it was very emotive and driven by ideas like hope as opposed to issues. And so it’s almost unique in our history — the way in which people flocked to him, knowing little about him, knowing not very much about what he would do in concrete terms as president.”

Not that Obama hadn’t supplied the details. His 2006 book, The Audacity of Hope, outlines his positions on a range of issues, from health care to the Iraq war. Then there is his 1995 memoir, Dreams from My Father, which startles in its literary depth and provides an unusually candid profile of what would become a major political figure.

If you want to know who I am, read my books, writers will say. Yet the paradox of Dreams is that the more layers of himself that Obama reveals — those of an intelligent, searching, conflicted, supremely confident young man, an amalgam of identities and ambitions — the less knowable, in some ways, he becomes. In writing about his family, his friendships, and his adventures in community organizing, he displays a novelist’s insight into the human scene: he’s an outsider, really, an observer, an artist even, who becomes aware that people will listen to his opinions — a discovery that makes him, as he says in the book, “hungry for words. Not words to hide behind but words that could carry a message, support an idea.” This is a controlled, reflective mind that stands in jarring contrast to the simpler machinery of George W. Bush. A subtle intelligence has always been an occasion for suspicion, but there’s every chance that Obama’s good-faith political approach will melt some of that distrust. Hofstadter diagnosed and described the paranoid spokesman; Obama wants to understand him and find common ground.

Us versus Them?

“Paranoia is no more dead after the election than irony was dead after 9/11,” says Jonah Lehrer ’03CC, author of Proust Was a Neuroscientist and proprietor of the brain science blog The Frontal Cortex, on which he extolled Obama’s “metacognition” — his ability to think about his own thinking. “The big phenomenon at work in presidential elections,” Lehrer says, “is that we all turn into partisan hacks for several months every four years. It has to do with the way the brain processes information. This gets back to cognitive dissonance and other phenomena that allow us to filter information and choose teams — and when it comes to politics, those teams are political parties. And since we’re ultimately social animals, we parse the world into Us versus Them, and choose our facts accordingly.”

Hofstadter understood this basic foible of human nature and its implications for democracy. In his canonical book of essays, The American Political Tradition, he portrays the Founders, who were landowning men of affairs, as reluctant to extend democracy to the yeoman farmer class. Hofstadter shared this wariness, though not for fear of his property: his American heartland is a breeding ground for anti-intellectualism and nativist hysteria.

“‘The Paranoid Style’ reflected Hofstadter’s fears about mass movements,” says Eric Foner, DeWitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia and, like Dallek, a Hofstadter student. “He was an elitist, basically. Or a managerial liberal. He really believed that experts should be conducting politics, and especially after McCarthyism.”

According to historian David S. Brown, author of Richard Hofstadter: An Intellectual Biography, Hofstadter saw the mob tendencies that characterized the McCarthy and Goldwater cults as a permanent feature of the democratic state. “What Hofstadter was talking about was in many respects a political mood,” Brown says, “and that mood may be set off more at different times depending upon the circumstances. Hofstadter was critical of democracy in that respect.”

But what would he think about the recent election?

“I suspect he would be pleased with the outcome,” says Brown. “He was heartened by the civil rights movement, he marched at Selma, and there’s the question of how much he saw himself as a minority [his father was Jewish]; so I think he would be heartened.

“And I think he would have had fun with Palin. Had the New York Review of Books come to him to write on the Republican team, I’m sure that in a very gentlemanly yet cutting way he would have put on a real Menckenesque show.”

Influenced early on by the Progressive historian Charles Beard 1904GSAS, who interpreted history through the prism of economic conflict, Hofstadter eventually became associated with the “consensus historians,” who saw American political society as held together by core values like individual liberty, private property, and entrepreneurial capitalism.

In that regard, Obama might be called a consensus president: wanting to bridge the partisan divide to solve problems, he focuses much of his rhetoric on themes of commonality.

“Let us resist the temptation to fall back on the same partisanship and pettiness and immaturity that has poisoned our politics for so long,” the president-elect said during his victory speech on November 4 in Chicago’s Grant Park. “Let us remember that it was a man from this state who first carried the banner of the Republican Party to the White House — a party founded on the values of self-reliance, individual liberty, and national unity.”

Hofstadter, a son of the Great Depression, might have winced at Obama’s nod to the bootstraps romanticism of the Right. But Obama, the ultimate self-made man, is after bigger game.

“Obama is going to try to create a government of national unity,” says Dallek, “and I think he does have this powerful impulse toward consensus.”

Whether that means he’ll make converts out of the Congressman Brouns and Congressman Kings of the world (to say nothing of their constituents), and foster a new political culture that pushes the paranoid style further into the cheap seats of the political arena, remains to be seen. But there is no doubt that Americans, in electing Obama, have taken a step in that direction — and changed their country in the process.

“There is a change, without question,” Dallek says, “but how far it reaches we’ll find out over the next four years. Part of it, of course, depends on how skillful a politician and how effective a leader Obama proves to be. If he’s as masterful a president as he was a campaigner, then I think we’ll see this as a major turning point in American politics.”