This spring, Columbia’s libraries acquired several collections that will benefit key areas of scholarship at the University.

The acquisitions include the archive of documentary filmmakers Albert and David Maysles; a collection of works by the darkly comic writer-illustrator Edward Gorey; the archive of the Committee to Protect Journalists; and the papers of Fyodor Chaliapin, the preeminent Russian opera singer of the early 20th century, and his son Boris Chaliapin, a prolific midcentury Time magazine cover artist. The Maysles collection was purchased by Columbia; the others were donated.

“I’m always amazed at what we’re able to bring in and make available to scholars and students,” says Michael Ryan, the director of Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. “Each of these new collections speaks to a different constituency. The variety is what makes a big research library an interesting place.”

Give 'Em Shelter

The filmmaking brothers Albert and David Maysles helped to pioneer the direct cinema movement of the 1960s, which invested the documentary with new realism and intimacy. Their accomplishments were enabled by new technical innovations: lightweight 16mm cameras with portable synchronized sound that allowed the Maysles brothers to slip unobtrusively into people’s lives, as they did while making Grey Gardens, Gimme Shelter, and Salesman.

Film historians can gain an intimate view of the Maysles brothers’ working methods in their archive, which Albert sold to Columbia in May. (David died in 1987.) Included are production files on completed and unrealized films, decades’ worth of correspondence, scrapbooks, clippings, notes, and financial records. “With each passing year, it becomes more and more apparent that the documentary movement known as cinéma vérité or direct cinema revolutionized the way we see the world, and the relationship between filmmaker and filmed subject,” says film professor Richard Peña. “As Columbia expands its commitment to the scholarly study of film, original source materials such as the Maysles papers will prove an invaluable resource for students.”

Preserve and Protect

When Terry Anderson, the chief Middle East correspondent for the Associated Press, was kidnapped in Beirut in 1985 and held hostage for nearly seven years, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) lobbied hard for his release. And when Cameroonian newspaper editor Germain Cyrille Ngota Ngota died while in pretrial detention this past April, CPJ pressed Cameroon’s president for an impartial inquiry.

Since its founding in 1981, CPJ has saved documents, photographs, clippings, and correspondence pertaining to many such cases. Now CPJ has donated its archive to Columbia, where it becomes part of the Center for Human Rights Documentation and Research, which already holds the archives of Amnesty International USA, the Committee of Concerned Scientists, Human Rights First, and Human Rights Watch.

“This is a record of our own history,” says CPJ executive director Joel Simon, “but it is also a history of a global movement that has emerged in the last couple of decades: the press-freedom movement, which is intimately connected to the humanrights movement.”

Fathers and Sons

Fyodor Chaliapin was one of the great opera singers of the 20th century, a Russian basso profundo whose powerful, emotional voice complemented his novel, naturalistic acting style. At the Met, in 1907, he portrayed Basilio in Rossini’s The Barber of Seville as “a vulgar, unctuous, greasy-looking priest who picked his nose, wiped it on his cassock, and kept spitting all over the stage,” wrote critic Harold C. Schonberg. “This was realism with a vengeance, and Chaliapin was taken apart.”

The family papers of Fyodor Chaliapin and his son Boris, a gift of the estate of Boris’s wife Helcia, are fi lled with evidence of Fyodor’s huge personality. There are photographs of him in elaborate stage costumes, bearing ferocious expressions; correspondence and clippings from his 1933 voyage to Hollywood to make Adventures of Don Quixote, his only film; and personally inscribed photos from Toscanini, Puccini, Rimsky-Korsakov, Tolstoy, and Chekhov.

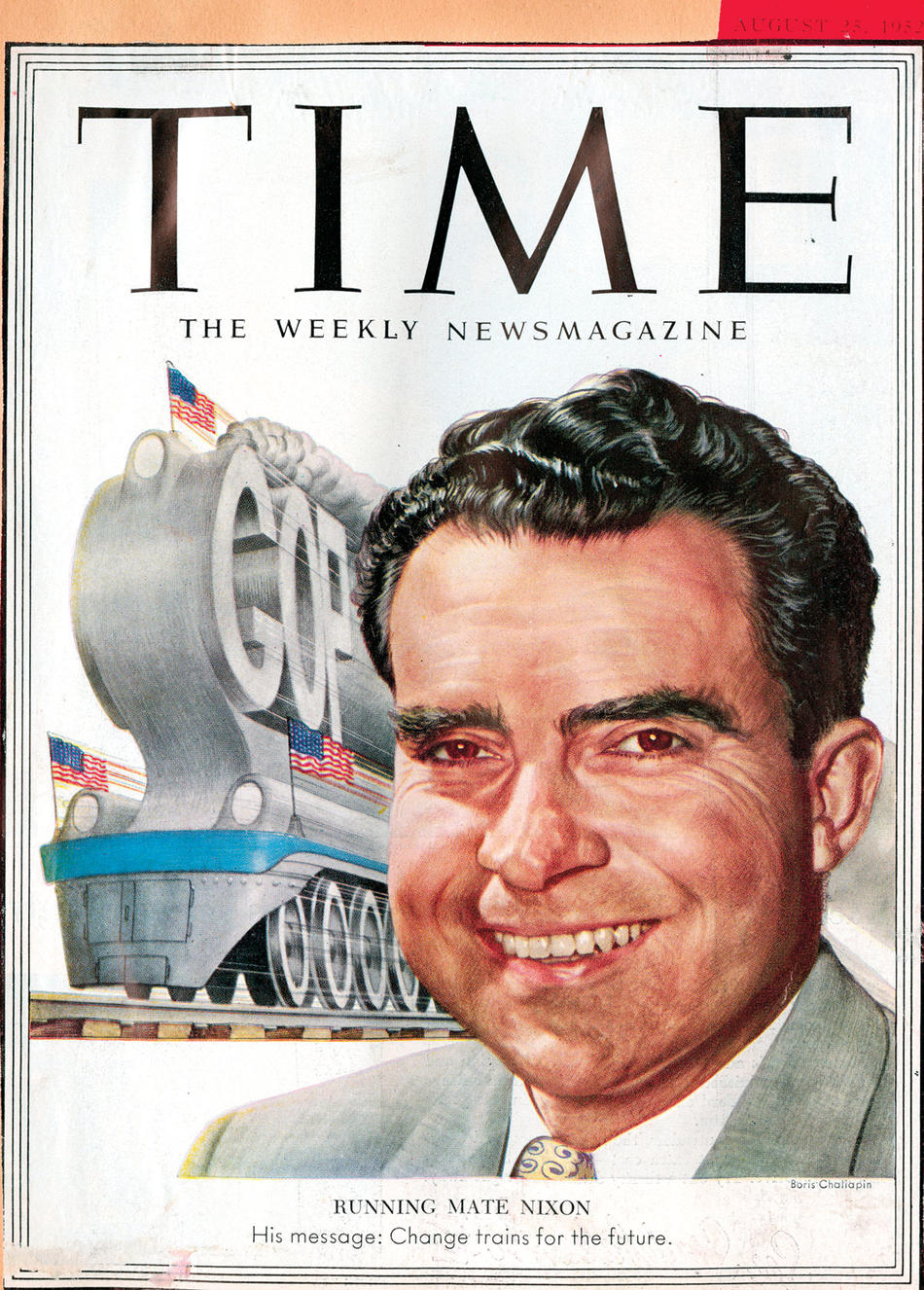

Boris, an artist, never achieved his father’s fame, but his portraits were seen by millions on Time magazine covers published between 1942 and 1970 — a total of about 400 images commissioned for $2000 apiece. The Chaliapin papers include a notebook of Boris’s exquisite charcoal nudes, portraits of prominent Russian ballet dancers, and an envelope of original costume designs.

The collection will be incorporated into the Bakhmeteff Archive of Russian and East European Culture, the second-largest repository of Russian émigré materials in the U.S.

Gorey's Ephemera

The artist and writer Edward Gorey crafted ominous but playful worlds full of suspicion and languor. Perhaps best known for his animated title sequence for PBS’s Mystery! series, in which elegant party guests mingle as a corpse sinks quietly into a pond, he also published short, gothic-tinged picture books for adults, with titles like The Gashlycrumb Tinies, The Unstrung Harp, and The Doubtful Guest.

Andrew Alpern '64ARCH, an architectural historian and attorney, recently donated his personal collection of approximately 700 Gorey works to Columbia. Alpern accumulated much of his collection at the same shop that helped Gorey launch his career: Gotham Book Mart, in Manhattan. Alpern and Gorey met at the shop and in 1980 collaborated on a project that Gorey named F.M.R.A. (say it aloud): a boxed set of loose printed drawings and lettering on various sorts and sizes of paper. One copy comes to Columbia as part of Alpern’s gift, along with nearly every edition of every work Gorey published, plus illustrations for book covers and magazines, original drawings, etchings, posters, and printed ephemera.

“There is so much substance in what superficially seems like some very strange words and some very strange pictures,” says Alpern. “You read the little book one time, and then you go back a few months later and it’s different. That’s the mark of really good stuff.”