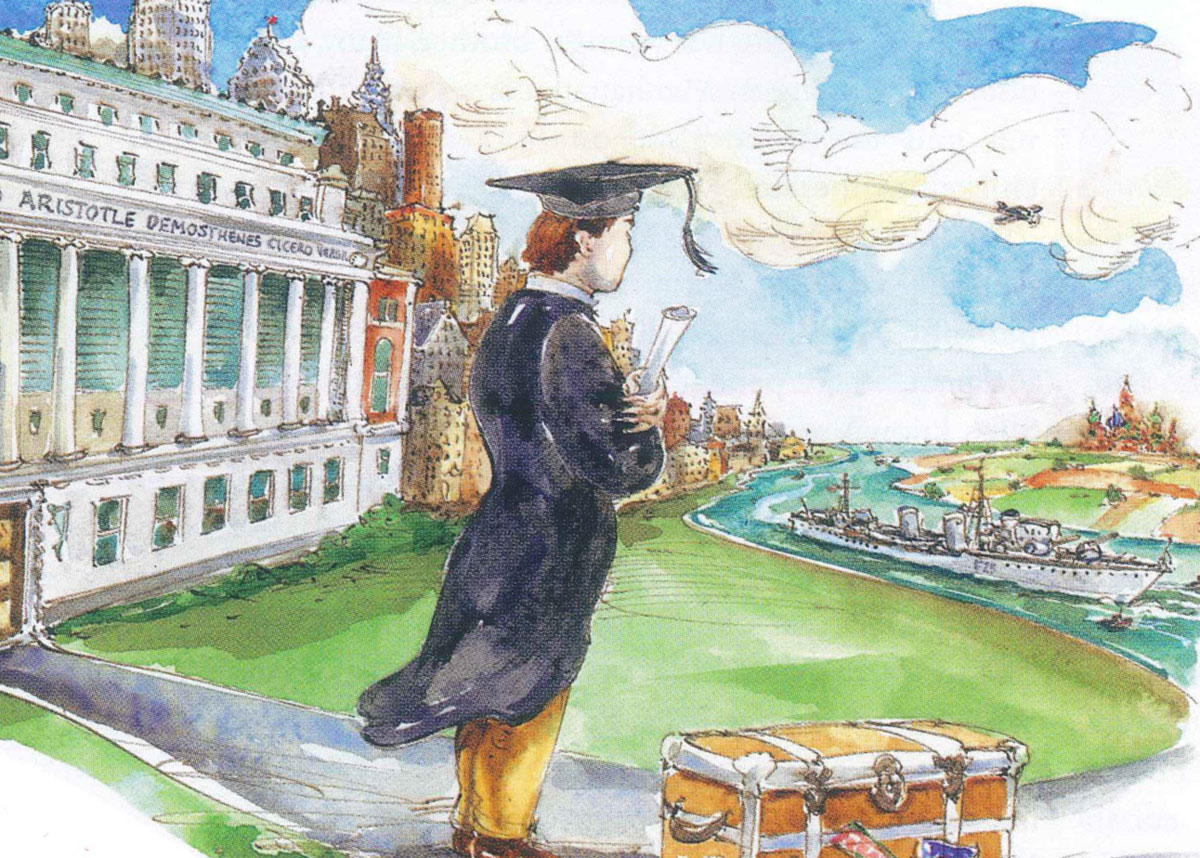

How exciting and a little scary it was, having just turned 16, to be a freshman at Columbia College. Looking at the names of the immortal writers and philosophers on the facade of South Hall (later renamed Butler Library), I had mixed feelings knowing that I was supposed to read and understand most of them in my Humanities course. It was September 1937. I couldn't have known it then, but as the world's stage was being set for a hot war followed by a cold war, my role in that drama would be shaped by Columbia.

But first I had to graduate. In addition to my studies, leading to honors in French and election to Phi Beta Kappa, I took part in Varsity Shows as a bit player in the musical comedies of my talented classmate I. A. L. Diamond, who wrote the book and lyrics each of our four years. He was snapped up by Hollywood and became Billy Wilder's collaborator on such films as The Apartment and Some Like It Hot. I tried to compete with Diamond while we were undergraduates by submitting a script of my own, and failed. However, I continued at Columbia doing graduate work toward my master's degree, and coauthored the book and lyrics for Saints Alive, the Varsity Show of 1942. (The star, Gerald Greenberg '42CC, became famous as Gerald Green, a novelist and award-winning TV writer.)

Another highlight at the College was joining one of the three Jewish fraternities, Beta Sigma Rho, which was located in a brownstone on 114th Street. I would walk there from morning classes to have lunch and enjoy the camaraderie of my fellow students. With social contacts difficult for those like me, who commuted by train from Long Island and missed dormitory life, the frat house was a home away from home. We would gather around the upright to sing the latest pop tunes and Columbia fight songs and recite our favorite limericks, some of which are unprintable. One that can be quoted here concerned a Romanian monarch and his mistress: "Said the beautiful Magda Lupescu/When King Carol came to her rescue:/'Vot a vunderful thing to be under a king/Is democracy better? I esk you."'

In 1940, when the fast-food chain Chock full o'Nuts opened a small café on the southwest corner of 116th Street and Broadway, it ran an ad in Spectator announcing a limerick contest over the next six weeks. The first two lines of contest no. 1 were provided, and the challenge was to complete the poem, with a prize of $5 for the cleverest entry. I gave it a try. Their lines began: "At Chock full o'Nuts 'cross the street/Where sophs and their profs often meet..." My last three lines were: "You can take it from me/That they always agree/It's a treat the elite couldn't beat." A week later, Spectator printed the winning limerick and the name of the writer - it was me! I submitted entries each week and won three of them. Full disclosure: the contest rules stipulated that a winner could not enter again. So I persuaded my closest frat brothers, Eddie and Charlie, to let me use their names. They both won five bucks, and the grand prize of $100 went to Charlie. He handed me the check, and I gave him the agent's fee. His psychology prof hailed his triumph, suggesting that he buy beer for the class, so Charlie's net gain was pretty small.

Less than six months after graduation, Pearl Harbor was attacked and we were suddenly at war. Eddie was in graduate school with me, and his father, who was in the import business and had visited Japan, advised me to study Japanese because America would soon need translators and interpreters. A crash course was offered in the spring semester, and I seized the opportunity. Professors Hugh Borton and Harold Henderson, along with two Japanese assistants, taught us, and by June our class was reading, writing, and speaking rather well. When recruiters from the U.S. Army and Navy came to Columbia in search of smart students who could learn Japanese quickly, they were impressed that our group already had a head start and persuaded most of us to enlist. I chose the Navy, and in June 1942, I entered the Japanese Language School at the University of Colorado in Boulder. My wartime service was spent in Washington at a top-secret Naval Communications unit, where we used our Japanese in code breaking and translation.

In 1946, after I was honorably discharged, I returned to New York and got a job at the Voice of America (VOA) writing news and features, and considered resuming research at Columbia in 18th-century French literature. By 1947, the Cold War had started and the VOA launched broadcasts in Russian to the Soviet Union, so I decided to return to my alma mater - but not for French. Instead, I applied for admission to the newly established Russian Institute on the GI Bill. A two-year curriculum in five disciplines covered history, government and law, economics, international relations, and Russian language and literature. In 1949, I received the Certificate of the Institute as a member of the second graduating class, along with the MA from the Department of Slavic Languages.

While taking a course on Dostoevsky in Philosophy Hall, taught by Professor Ernest J. Simmons, I met my future wife, Gloria Donen, who was a WAC veteran studying for her MA in the same department. We were married in June 1950, and a few weeks later, we both were hired by Columbia's Bureau of Applied Social Research to take part in the Harvard Refugee Interview Project in Munich, in the American occupied zone of Germany. Professor Philip E. Mosely had strongly recommended us for the team that was responsible for interviewing displaced persons from the Soviet Union who remained in the West after the war. The project became famous as a pioneer in research that assessed the strengths and weaknesses of the Soviet system, and enriched America's understanding of our Cold War adversary. Gloria and I were thrilled to have participated in that Red Letter Year: Munich 1950-1951, the title we gave to the book she published recently about our experiences, made possible by our Columbia education.

In 1952, I was hired by Radio Liberty, the U.S. shortwave station, to prepare broadcasts to millions of Russians and other ethnic groups within the USSR. For the next 33 years I held several executive positions in New York and Munich in the area of policy and programming. In 1959, thanks to a generous travel grant from the Social Science Research Council, I spent five weeks in Moscow, Leningrad, and Kiev doing postdoctoral research on state-subsidized theaters for children, and absorbing the reality of everyday Soviet life.

Gloria and I visited the USSR under Gorbachev, and post-Soviet Russia in the 1990s. Today, after many years of retirement, I still keep in close touch with the Russian (now Harriman) Institute, where I have lectured on a variety of topics, and plan to continue. Now, when crossing the campus as an octogenarian dinosaur, I feel as if I'm in a time warp: again a young freshman wearing a blue dink, never dreaming of the exciting and fulfilling future virtually programmed for me there. My Columbia? Yes, indeed.

Gene Sosin is the author of Sparks of Liberty: An Insider's Memoir of Radio Liberty (Penn State, 1999). He and Gloria '49GSAS live in White Plains, NY, where they write and lecture. Their son, Donald '76GSAS, is a composer. Daughter, Deborah, a writer, helped carry GEne's dissertation into Low Library at the age of four.