In 1945, I left rural West Virginia for the first time to attend Columbia’s School of Library Service. I was 22, and I planned to take my degree and return to my undergraduate alma mater, West Virginia Wesleyan College, where they were building a new library. I was valedictorian of my class, and they wanted to put me in charge. But in those days there weren’t many librarians in the country, and there was no library school in West Virginia. The job was all but promised to me after I graduated from Columbia. I had heard stories about New York from my mother, who had attended a summer program at Teachers College in 1917, and I couldn’t wait to visit all of the places she talked about.

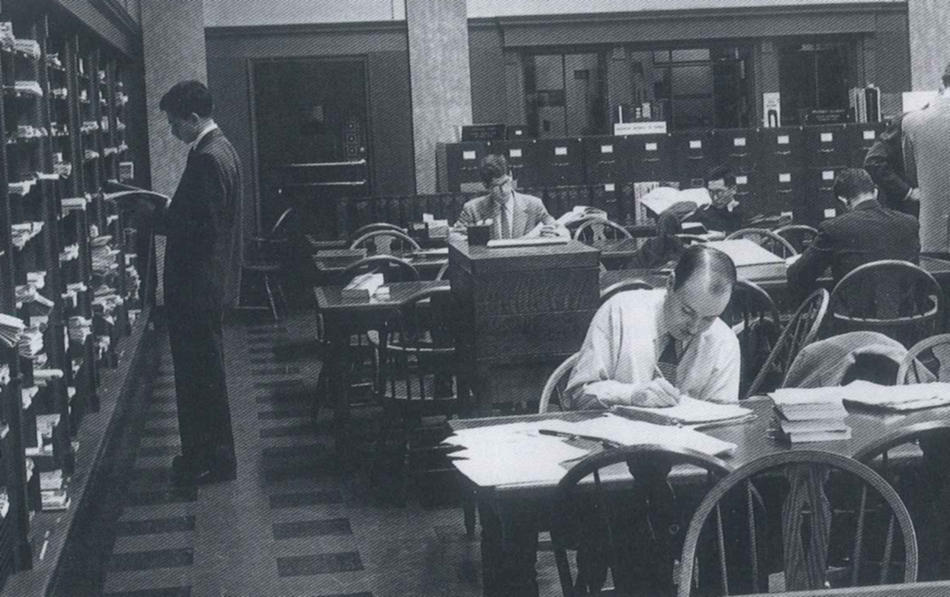

Columbia gave me a scholarship, and it changed my life. To earn living expenses for my room in Johnson Hall (now Wien Hall) at 116th and Morningside Drive, a dormitory for female graduate students, I worked part time at the beautiful library that was soon to be named for the retiring president, Nicholas Murray Butler.

I worked as the evening assistant in charge of the newspaper and document reading room on the second floor. I will never forget one old man who stationed himself near the large unabridged dictionary each evening. At that time, anyone, not just students, could patronize the library. Some senior citizens came to read and, perhaps, keep warm in winter. Usually I made eye contact when patrons came in, but the old man never looked my way, and he seldom spoke. When he arrived, he took off his ragged coat, huge scarf, knitted hat, and gloves and threw them on a wooden table, which he claimed as his. He took off his boots, and then he opened his battered satchel. He seemed impoverished, self-absorbed, and intent on reading the New York Times. He looked ancient to me because I was so young, but perhaps he was in his 50s.

No one dared invade his space. No one spoke to him. Furthermore, he monopolized the current issue of the New York Times. He spread out the newspaper and bent over the pages for a closer look. Sometimes he asked me for a pencil sharpener, and I found it difficult to understand his heavily accented English. He underlined words and at times used a magnifying glass to look them up in the dictionary. I could tell right away that he was trying to teach himself English.

The library closed at 10 p.m., but the old man never wanted to leave. One night he seemed deliberately slow as he pulled on his boots. Finally he left, and I finished cleaning up his mess. When I was ready to go, I walked down to the front lobby, but the heavy doors would not budge. I was locked in. I faced the prospect of spending the night in the lonely, darkened hallways of Butler Library. The building seemed larger than ever. I was terrified, no longer the self-confident young woman who had laughed with friends and family back home when they questioned how I dared venture into such a dangerous metropolis as New York City. I was truly frightened.

To my great surprise and relief, a co-worker emerged from the next-door magazine room. A thin young guy, he looked as shocked as I felt when he realized we were stuck. He told me to sit on the balustrade of the stairway to the right of the front door while he ran calling through the echoing hallways of each floor. Finally, at the far end of the fourth floor, he saw a light shining. We were fortunate, because the head librarian, Carl White, happened to be working late. I had never met him, but I recognized him in the dark suit he typically wore to work. He seemed disturbed to see that something had gone wrong in the management of his institution. “Don’t let this happen again,” he said sternly as he used his key to let us out. We two young workers were thankful to escape.

I continued to battle with the old man at closing time for the rest of the year, but I never again got locked in. And although I worked hard, I squeezed in as much sightseeing as possible. This included going to the Thanksgiving Parade and the Easter Parade, which started with Easter sunrise services at Radio City Music Hall. On quiet Sunday mornings, my friend Dorothy Warren ’46SLS and I often took the subway all over the city to join the congregations of cathedrals and historic churches. I saw Oklahoma! on Broadway and got standing-room tickets to the Metropolitan Opera. I felt culture shock when I visited the street markets and restaurants of Chinatown — I had never met a person from China in West Virginia, or eaten Chinese food! And in spite of comprehensive exams in summer school, I managed to swim at Jones Beach and spend an afternoon at Coney Island.

In October 1946 I graduated with honors. I did not take the job at the college in West Virginia. What young woman would want to return to a small coal-mining town after she had had a taste of New York City? Instead, I got my first job at a library at Northwestern University, and ended up settling in Springfield, Mo., in 1955. For 40 years I was the head of the children’s department of the public library, keeping up with the wonderful world of children’s books and watching kids develop their minds. I have returned to campus a few times, most recently in the summer of 2005 to visit my daughter Barbara. We took a walk through the library, and I was flooded with memories.