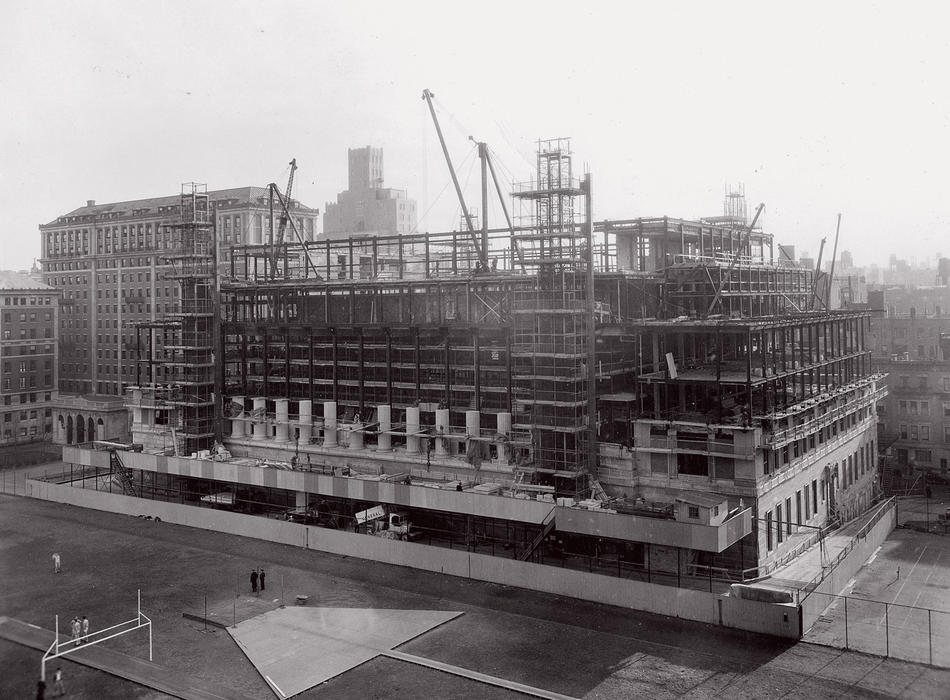

In the summer of 1932, steel beams began rising from a giant crater in South Field. Over the following months, the hulking metal skeleton would be clad in a classical revival–style raiment of brick and limestone, with 14 Ionic columns lining the facade. By the autumn of 1934, South Hall was complete.

“It is distinctly a laboratory library — that is, a library building designed not merely for the storage and distribution of books, but for the constant working with books,” President Nicholas Murray Butler told reporters that September. Two months later, on November 30, 1934, Butler presided over the dedication of the building in the main reading room. Columbia, long in need of a larger and more amenable space than Low Library, now had a cutting-edge facility where books would receive all the care that technology could provide: air-conditioned stacks, conveyor belts, and non-glare lighting.

South Hall’s $4 million price tag was footed by the philanthropist Edward Harkness, an heir to the Standard Oil fortune and a benefactor of Columbia’s medical campus. The architect was James Gamble Rogers, whose credits included the College of Physicians and Surgeons. The Depression imposed its share of compromises on South Hall — the finished building would have room for just under 3 million books, about half of what library director Charles Williamson had envisioned in 1927 when he first wrote Butler about the inadequacies of Low — but that didn’t stop the president from calling his new athenaeum “as finely planned and as well constructed an academic building as is to be found on either side of the Atlantic.” In 1946, a year after Butler stepped down as president of Columbia, the building was renamed in his honor.

Now, to mark the 75th anniversary of Butler Library, a permanent photo exhibition is taking shape on the building’s third floor, across from the main reading room. Included is a series of 18 photographs that document the library’s construction, from excavation to completion, as well as images depicting student life in the library over the decades. (We note a smoker or two in the photo at left.)

Today, Butler, with its private reading spaces, 24-hour access, and coffee bar, has become, in part, an enormous study hall, filled with laptops and headphones and spill-proof mugs. Smoking, of course, is no longer allowed, but one can still do something nearly as quaint: Check out a book.