September 23, 1948: Carl W. Ackerman, dean of Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism, welcomes 98 aspiring journalists to the University. We show up for the first day of class to find that a tricky exercise awaits us. The day is to be spent exploring New York City by subway.

At the 116th Street station, we buy a little red book (not Mao’s) detailing the subway system. Equipped with this guide and a pocketful of dimes, we go off to make a list of sites likely to be in the news this year. The lights burn late into the night at the J-school building. Dean Ackerman, relaxed and smiling, welcomes back stragglers, while Professor Roscoe Ellard anxiously consults his list of still-missing persons.

The exercise is meant to help us prepare to cover the presidential election on November 2, between New York’s Republican governor Thomas E. Dewey and Democratic incumbent and underdog Harry S. Truman.

November 2, 1948: In the morning we gather at the J-school newsroom to get our assignments for the election. A five-page handout gives the details. Mine are as follows:

“Christiansen, with a camera, and Neuman will cover Governor and Mrs. Dewey. Pick the Deweys up about 3:00 p.m. Christiansen will take pictures and write a story or stories. Neuman will be charged with an overall story on how the Deweys receive the returns.”

Margaret Neuman and I are stunned. “We’re going to see the next president!” Margaret says. “What do you think we should wear?” But I have more pressing concerns: me with a camera. “What camera?” I ask Professor Ellard. “You can use your husband’s,” he replies.

My husband, Don, had come to New York City with me. I was to be a journalism student at Columbia; he would be a picture editor at Science Illustrated magazine. He had trained me to help out in the darkroom, but I’d scarcely touched the camera. It was a Speed Graphic, a bulky, classic press camera — the primary military camera used in World War II. The Speed Graphic had produced pictures of astonishing clarity, including the photo of the American flag being raised at Iwo Jima.

The photographer controls every move made by this camera. He calculates the light exposure, gauges distance, trips the shutter (or shutters), and pushes a button that sets off the flashbulb. He gets one shot only before he must reload film and insert a new bulb. (President Truman called photographers of this era the “One More, Please” Club.)

I call Don from Columbia and ask if I can borrow the Speed Graphic to get pictures of Thomas Dewey. When he agrees, I bring out the question: “How do I use it?”

“Stay put,” Don says. “I’m coming.”

While waiting I write a naive think piece about the likely outcome of the election. Over the past few weeks I have read countless predictions that Dewey cannot lose and Truman cannot win. The two leading pollsters, George Gallup and Elmo Roper, agree. Roper even visited our class and explained the infallibility of the sampling procedure.

I write: “This election is not so much about who will win as it is about how many more votes Dewey will have than Truman.” This comment, as well as any pictures I might take, is to be used in The Front Page, our class publication.

Don arrives with the Speed Graphic and shows me how it works — or rather, how he makes it work. I hope I’ve got the hang of it. “Please don’t drop it,” he cautions and goes back to his job.

Margaret and I take the subway to the Roosevelt Hotel. The ballroom is a scene of joy. Smiles, slaps on the back, upbeat greetings, the happy expectation of victory. Tallies show nearly every Republican running for an office in New York is doing well. Refreshments abound. Dewey leads in early returns.

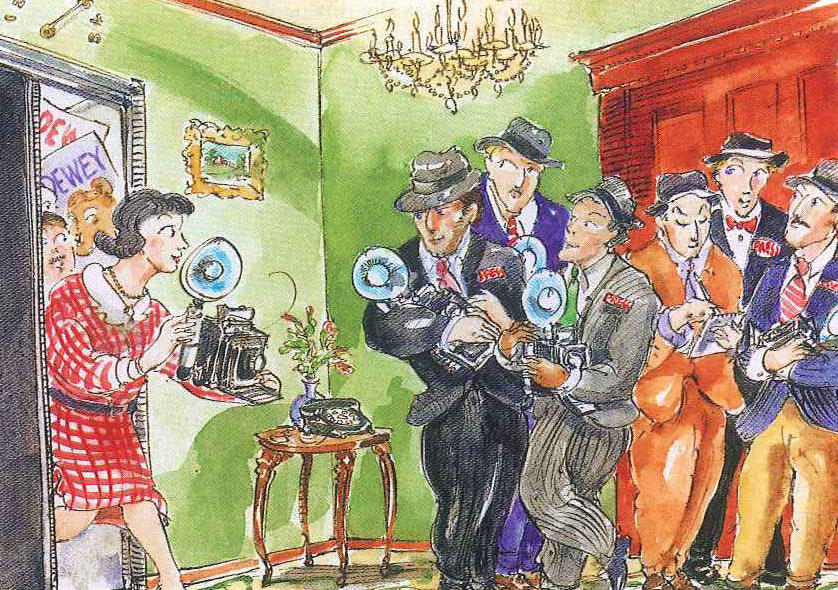

Margaret and I identify ourselves as journalism students from Columbia come to take a few pictures of the governor. Margaret looks professional in her new outfit; I am well covered by the bulky Speed Graphic with only parts of my red plaid skirt showing. We mill around the ballroom for an hour. No riots. No Dewey. It is now after 3:00, the time designated to “pick up the Deweys.”

We inquire as to the whereabouts of the governor and receive mixed responses. It is now dark. Apparently Dewey is in the hotel, somewhere on an upper floor.

Margaret and I are then beckoned to the elevator. We ride up to an undisclosed floor, where we are met by a swarm of Dewey’s aides and Secret Service agents. James C. Hagerty, Dewey’s press secretary, and Herbert Brownell, Dewey’s campaign manager, look us over. They are not terribly impressed with our student status, but because I am toting the Speed Graphic they good-naturedly allow me to join a group of photographers huddled by Dewey’s closed door. Margaret is excused and goes back to the ballroom. I am left alone to face Secret Service chief James J. Maloney and five of his agents. Their discussion of whether I should be allowed into Dewey’s presence is cut short when a New York Times photographer takes me by the arm and says, “She’s with me.”

Inside the room I feel a chill. Is it my anxiety about the camera? Or the abrupt change from the revelry of the ballroom to the formality encountered here? Or is it just the air-conditioning?

The governor, his wife Frances, and their two teenage sons are prim, courteous, and reserved. Mrs. Dewey has a beautiful corsage on her shoulder and is especially lovely in this predominantly male setting. She sends a sympathetic smile my way. Dewey seems preoccupied, answering questions tersely. The photo op begins with flashing lights, including one from my Speed Graphic. The clicking of camera shutters is followed by a thank-you to the governor and his wife, and we leave.

I take the elevator down to the ballroom, which appears less cheery than when I left it. “What’s up?” I ask Margaret. “Returns are coming in from California and they’re not good for Dewey,” she says. So the vigil begins.

Dewey is comfortably ahead in New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and his native Michigan. But there is worry about the West and the Farm Belt. The South, on the other hand, is split. Truman edges up from second to first. Dewey moves back to a strong first as new votes pour in from industrial areas. Later, as Wisconsin and Minnesota weigh in, Truman takes the lead. The seesawing would continue until late in the morning of November 3.

With the mood ebbing at the Roosevelt, Margaret and I consider going over to Democratic headquarters at the Biltmore Hotel. Our man from Columbia, Griff Davis, has sent word that the food is good and the Democrats lively, even though Truman is absent. It seems he has disappeared to a hideaway in Excelsior Springs, Missouri, eaten a sandwich, and gone to bed. Davis’s invitation is tempting, but we are too tired to accept and head home.

The following day in the darkroom at Columbia, I unload the camera to find my worst fears realized. There is no picture.

That same morning, Truman comes out of hiding and arrives at the Muehlebach Hotel in Kansas City, confident of victory. Only two of his aides, Matt Connelly and Bill Boyle, are still awake after an exhausting, nail-biting night.

At 11:14 a.m. New York time, Dewey concedes the election in the Roosevelt Hotel ballroom.

I am as shocked as anyone, but also incredibly relieved that a picture of Dewey would not be missed.

Patricia Christiansen was a school psychologist in East Los Angeles. She lives in Utah.