I have my heroes and the Right Reverend Paul Moore Jr. was — and remains — one of them. I covered Moore in my previous career as a religion reporter for the New York Times. He was charming, colorful, quotable, accessible, and, at times, larger than life. He stood six foot five and commanded attention with his words and deeds. When he died in 2003, at the age of 83, I was already teaching at Columbia, but I returned to the Times to write Moore’s obituary, which was given considerable prominence in the paper. I called him “the most formidable liberal Christian voice in the city” and recalled how he helped bring New York back from the fiscal crisis of the 1970s, how he fought for equality in church life for women and gays, and how he revived the seat of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, the massive Cathedral of St. John the Divine, right in Columbia’s backyard.

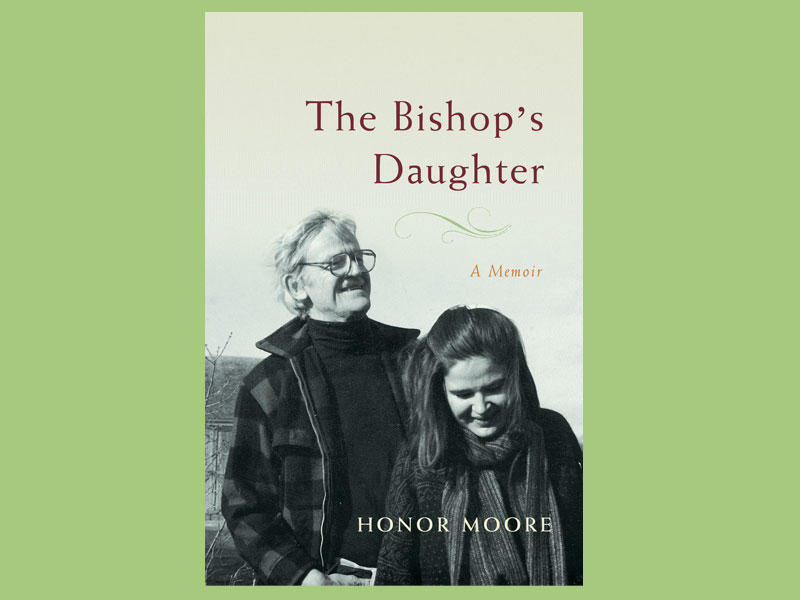

But now comes a book that reveals that Moore was far more complex than even those who knew him well imagined. In The Bishop’s Daughter, Honor Moore, his eldest child, reveals that he had a secret and active homosexual life even as he carried on as a family man and reared nine children.

I’m a pretty good reporter, so this is a book that leaves me wondering how this side of Moore’s life escaped my purview. I also wonder, perhaps naively, how a prince of the church could so wantonly violate both church law and the sanctity of marriage. And I puzzle over why his daughter would publicly reveal a secret that Moore himself labored so hard to hide.

The Bishop’s Daughter might best be classified as a “sexual memoir” of a father and daughter, who each in his and her own way — and, I hasten to add, quite separately — struggled with sexuality. Let me state at the outset that Honor Moore is a meticulous reporter and an eloquent writer. She researched her subject thoroughly, delving into her father’s past and talking to the major players in his life, including his friends and lovers, both male and female. Honor Moore is a poet with three published collections to her credit and the author of The White Blackbird: A Life of the Painter Margarett Sargent by Her Granddaughter. She has a brilliant eye for detail and often writes with emotional power. Moore also is an adjunct professor of writing at Columbia.

“My father’s extreme height made him seem even more distant,” she writes in one typically incisive passage. “I thought his tallness had to do with the brocades, with the music, the candles, and the gold crosses that preceded him down the aisle, that it rendered him closer to God.”

But let me also state that she is an angry, confused, jealous, and vindictive daughter, a child of privilege who lives the high life and seems not to count her blessings, only her emotional wounds. She writes far too much of the cocktail parties she attends, the restaurants where she dines, and the birthday presents that she gets, all of which, inevitably, disappoint her. But at the core of this book are her sexual exploits. She details the male lovers of her youth, her awakening as a lesbian, and then her return to heterosexual relationships.

Infidelity is part of this life. For example, although she is in a longtime relationship with a man 20 years her senior named Venable, she goes off to a writers’ retreat where the first day – at breakfast, no less – she meets and beds a Parisian named Daniel.

For a book with so much sex, The Bishop’s Daughter is strangely unsexy. The cavalcade of lovers and bedroom scenes quickly becomes a sad spectacle.

Perhaps the saddest relationship of all is the one Honor Moore has with her father. Even here, there is an undercurrent of sexual tension. When she is in her heterosexual phase, she brings home men nearly her father’s age. When the bishop marries a year and a half after his wife dies, his second wife is not much older than his daughter.

Hints of Paul Moore’s double life are sprinkled throughout the book, but the final confirmation comes well after the obituary I wrote of him in the Times was printed. When Moore’s will is read, a gift is left for a man no one in the family can identify. Upon investigation, Honor seeks out and meets the man who had a 30-year gay relationship with her father.

One of life’s bitter lessons is that our heroes are human. Paul Moore certainly was. He championed many good causes and led a life of service. My fear is that too many of his good works get lost in this book. He deserves better.