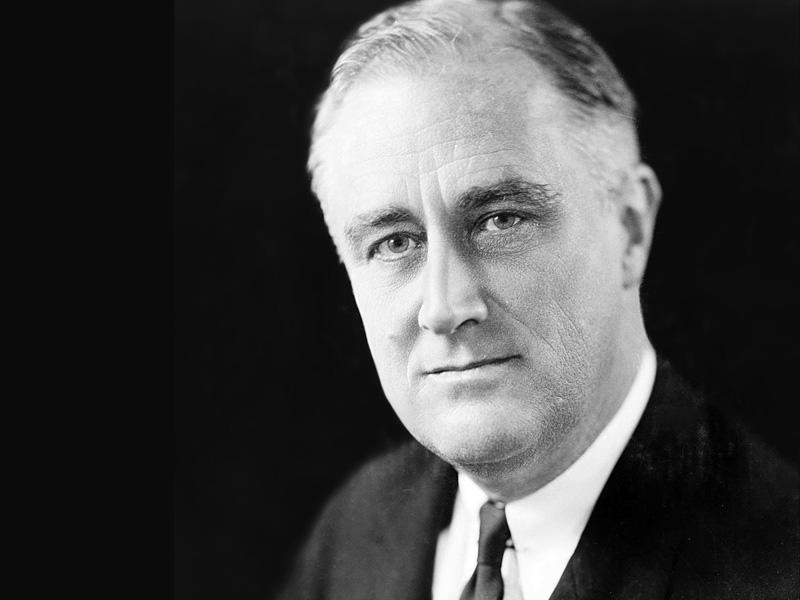

Who is the least-known president of the United States? As presidents, Fillmore and Pierce might vie for the palm. As a human being, Franklin Delano Roosevelt — whose exterior was universally known and who bestrode his time and ours — would until recently have been short-listed. Jean Edward Smith ’64GSAS has now made Roosevelt the man far less of an enigma.

FDR certainly bestrode my world. I spent World War II as a child just across the Potomac from him.

On April 12, 1945, I was at the end of my paper route when I heard, from the house of a customer, the words “Mr. Roosevelt will be buried at Hyde Park.” I assumed that one of the president’s sons had been killed in the war. FDR, who consigned all the other Mr. Roosevelts to mere mortality, could not need burying. I learned better when I got home. Two days later, FDR returned to Washington and I watched Harry Truman drive down Pennsylvania Avenue to receive his predecessor at Union Station.

All of which is to say that for the declining number who remember the extraordinary phenomenon that was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, no FDR biography can lack interest.

Jean Edward Smith is John Marshall Professor of Political Science at Marshall University, and author of John Marshall: Definer of a Nation and of Grant, a 2002 Pulitzer finalist. He has produced a biography that will probably stand as definitive unless substantial new material is uncovered. Smith does not seem to have unearthed any striking new facts, but his command of what is known is all-encompassing and his presentation phenomenal. He proceeds at three levels: the compact and fluent prose of the main narrative, the never-failing footnotes in which he provides the necessary background for the general reader with suggestions for further reading, and the endnotes in which he further documents the narrative and provides additional bonbons for the connoisseur.

Smith examines Roosevelt’s early life without a tinge of armchair Freudianism. He corrects the popular view of FDR as the child of a domineering mother and an old and distant father. (James Roosevelt was 54 when Franklin, his son by a second marriage, was born.) To the contrary, Sara Delano Roosevelt appears as deeply supportive, emotionally and financially, of her only child, and James Roosevelt was FDR’s best friend.

The picture Smith draws is of a gifted and privileged young man whose self-confidence took him triumphantly through the disaster of paralysis and the challenges of democratic politics and a world war.

FDR began his political career in 1910 by winning a state senate seat in a soundly Republican district that included the family estate at Hyde Park. The following year, he met Louis McHenry Howe, the Albany correspondent of the New York Herald, who quickly decided when covering FDR that, as he later said, “nothing but an accident could keep him from becoming President.” Howe almost immediately dedicated himself to the prevention of any such accident.

Howe, plagued by ill health and often described as “gnome-like,” was not to Eleanor’s taste, but they became close friends: politically and personally Howe was ER’s Pygmalion. He was a constant mediator between two formidable partners in a difficult marriage. He also served as an able surrogate, successfully campaigning for Roosevelt’s reelection in 1912 when FDR was knocked out with a bout of typhoid.

The next year, FDR joined the Wilson administration as assistant secretary of the navy. As Smith makes clear, FDR’s imaginative and activist performance during the war prefigured his presidency. He won a reputation such that he was on the Democratic dream ticket for 1920 with Hoover, whose party affiliation was still ambiguous. In the end, FDR became James Cox’s running mate and the ticket was snowed under by Harding and Coolidge.

Then, awaiting his political opportunities, he embarked on a career in business and law when in August 1921, at his summer home in Campobello, New Brunswick, paralysis struck. His mother urged him to retire to the life of an invalid country squire, but FDR seems to have regarded his paralysis as a minor blip in his career. His psychic recovery from that exception was fueled by determination and not a little denial (he seems to have thought, perhaps to the end, that some day he would walk), but also because he was accustomed to winning. He did not win the battle with his leg muscles, but he did triumph over any public perception that a man who could not walk could not govern.

He was fully back in play at the 1924 Democratic convention, when he moved painfully on crutches to the lectern to nominate Al Smith for president in a speech that did not win the nomination but that made Al forever “The Happy Warrior.” Four years later, a successful Smith persuaded a reluctant FDR to run to succeed him in Albany. He won a term, and then another.

The two terms were Acts One and Two. In the first, FDR freed himself of Al Smith, who was at loose ends after his defeat and urged FDR to retain his major advisers Robert Moses ’14GSAS, ’52HON and Belle Moskowitz. In Act Two, he confronted the Depression and sketched out what was to follow in 1933 and after.

And yet when he turned his attention from Albany to Washington, his self-confidence, coupled with the powerful but superficial quality of charm, led others, in the word of a successor, to misunderestimate him. Walter Lippmann’s acerbic judgment in 1932 was that he was “a pleasant man who, without any important qualifications for the office, would very much like to be President.”

The fight for the nomination was no cakewalk, but once it was in hand, Hoover was an easy act to follow. Before 1932, candidates waited to be informed of their nomination a month or so after the convention and made a routine speech on their front porches. Roosevelt electrified the country by flying from Albany to Chicago, where he promised a new deal.

In 1932, however, the presidential term still began on March 4, so Hoover had almost four months of lame-duckery, and by the time FDR took the oath, the nation’s banking system (much of which was closed) was in a state of collapse.

This was the context of FDR’s first inaugural. When he spoke of fear (“So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”) he was confronting a threat that was alive in the land.

Smith’s account of the first year moves sure-footedly between the political and the personal.

In Smith’s concisely detailed account of the first hundred days’ legislation, one understands the astonishing march of events that FDR drove. These are not merely reported but set in the context of their future. Footnotes relate court challenges, and in noting the great speed with which the first New Deal bills were drafted, Smith sets up an overconfident FDR, who, in a later chapter called “Hubris,” fails to fashion a Supreme Court more to his liking.

Meanwhile, back at the White House, we learn that Franklin and Eleanor did not see much of each other. They had separate bedrooms, (largely) separate dining rooms, separate coteries, and separate personal schedules. Eleanor seems to have dealt with Franklin largely through his secretary, Marguerite (“Missy”) LeHand.

FDR’s failures in his second term may be attributable to Louis Howe’s death in the spring of 1936. As Howe lay dying, he remarked to a visitor, “Franklin is on his own now.”

I once saw a photograph on a corridor wall at Campobello showing FDR at Howe’s funeral: devastated, for once bereft of his trademark ebullience. Smith’s selections from Howe’s advice to FDR, frequently sent by telegram with the practiced reporter’s compression, suggest the ways in which Howe had kept FDR’s persistent confidence from morphing into hubris.

FDR’s presidency remains so contentious that polemic is always a temptation, one which Smith avoids. In discussing Pearl Harbor, he does not explicitly clear FDR of the conspiracy theory that in order to intervene in the European war he provoked the Japanese attack. He merely documents the administration’s concern that an inevitable war with Japan would complicate an inevitable war with Germany, and its assumption Japan would attack the easiest target: the nearby Philippines. Unaware of the strategic and tactical brilliance of Admirals Yamamoto and Nagumo, FDR regarded Pearl Harbor as impregnable.

In Smith’s account, FDR was not just a morale-boosting, charismatic commander-in-chief, but a capable strategist as well. He quotes Churchill, lodging in the White House shortly after Pearl Harbor: “[FDR’s] breadth of view, resolution and his loyalty to the common cause are beyond all praise.” Later, after the Casablanca conference, Churchill concluded, “he is the greatest man I have ever known.” It is unlikely that when Smith quotes these encomiums he does not in large part assent to them.

Yet this admiring biography is never tainted by hagiography. Smith describes FDR’s internment of Japanese aliens and Japanese-American citizens quite simply: “one of the shabbiest displays of presidential prerogative in American history.” And he goes on to explain in detail just why the internment was not merely a legal abomination but one without any claim to reason of state.

Smith’s epigraph is worthy to have been written in Latin: “He lifted himself from his wheelchair to lift this nation from its knees.” His conclusion is that Roosevelt “proved the most gifted American statesman of the twentieth century.” Anyone who would dispute this judgment must first read this remarkable biography word by word, footnote by footnote, endnote by endnote.