The face staring out at us from a passport photograph on the cover of Meyer Schapiro Abroad: Letters to Lillian and Travel Notebooks is not that of a man but of a boy, with a shock of dark hair, shining eyes, and a mouth that is ready to break into a smile. The year was 1926. Schapiro ’24CC, ’35GSAS was 21. I repeatedly had to remind myself of that astonishing fact as I read the letters of this erudite and self-confident fellow who raced across Europe, through towns large and small in France and Spain and Italy, as well as the Middle East, investigating the glories of Byzantine, Early Christian, and Romanesque art. I cannot imagine a more touching, tender, or compelling portrait of the scholar as a young man.

The Lillian to whom these letters were addressed was Lillian Milgram, Schapiro’s fiancée. She was finishing her medical studies at New York University. He was working on his PhD at Columbia. Meyer and Lillian would marry in 1928. She would have a career as a pediatrician, while Schapiro would become a legendary scholar and teacher, admired for a range of interests that included seminal studies of Early Christian, Romanesque, Gothic, and 19th- and 20th-century art. Later in life, Lillian assisted Schapiro in gathering the essays he had published for decades in a series of books, beginning with Romanesque Art (1977) and Modern Art (1978); volumes still were appearing when he died in 1996. Theirs was very much a New York story, of young, brilliant Jews from immigrant families who embraced all the possibilities that America and, by extension, the world had to offer. Reading these letters, one finds the world opening up wider and wider. There were friends everywhere Schapiro went. “Such connections are inevitable,” he jokingly wrote after a Parisian encounter; “even in the North Pole I shall find Eskimos who have met N.Y. anthropologists whose cousins know friends of mine.” But along with the familiar faces and the far-flung family members he met in Palestine, there was the excitement of familiarizing himself with the unfamiliar, with the churches, monasteries, and libraries where Schapiro examined carvings, studied the engineering of Romanesque buildings, and explored the texts and illustrations in countless manuscripts.

Reading through the letters, I have the impression that many of the scholars and librarians and church officials Schapiro met were delighted by all that this Jewish boy from Brooklyn already knew. And even if they were skeptical, they could hardly deny his accomplishments. After Schapiro visited Bernard Berenson in his home outside of Florence, for example, the great connoisseur wrote to Kingsley Porter, a leading scholar of Romanesque sculpture and architecture: “Yesterday a very handsome youth named M Shapiro [sic] sent up his card on which was written Columbia Univ.” I hear a strong note of irony in Berenson’s commenting that Schapiro could discourse “as smartly as Solomon” and that “he has painted sculpted architected. He is acquainted with the entire personnel of the arts and the antiquities.” (Schapiro may well have been a bit ironic about Berenson, too, another American Jew, this one from Boston, who had turned himself into a European aesthete.) And yet, what I take away from Berenson’s letter, above all else, is a sense of Schapiro’s genius for making people pay attention, for leaving them in no doubt that he was a somebody.

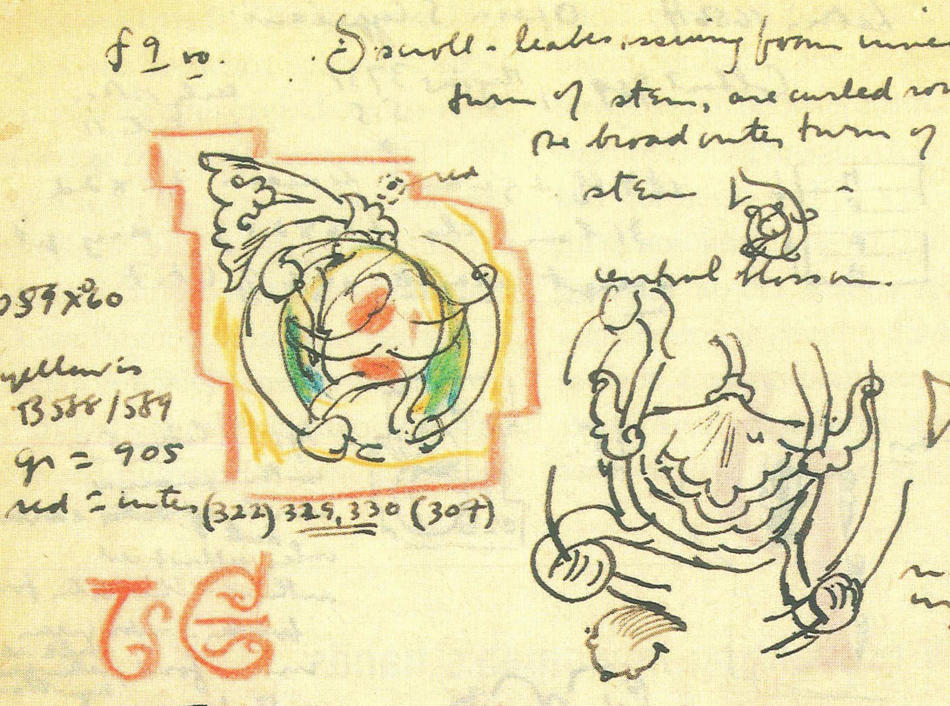

This beautiful book is a love story, and not only because the letters were addressed to the woman Schapiro loved. He was in love with the bounty of the Old World, remarking of Jerusalem that “The surrounding hills are a romance of roads, churches, tombs, and villages of stone, superposed — ” After receiving his BA from Columbia with honors in art history and philosophy, Schapiro found himself savoring the experience of engaging with works of art up close. He remarked toward the end of his time in Europe that “the greater part of the journey’s experience was in learning by touching, seeing & moving about objects — school now seems strangely passive or another habit with other ends. I love architecture all the more.” The pages from his travel notebooks that compose the second half of this volume reflect the immediacy of his experience, captured in striking studies of carved capitals and initial letters from illuminated manuscripts. These travel notebooks, now preserved in the Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library, are the work of a young man who had seriously studied drawing and painting and who had considered becoming a painter. Schapiro’s drawings are much more than transcriptions. There is an analytical force and a lyric delicacy to his pen strokes. The elegant arrangement of images on some of these pages achieves an abstract power.

The beguilements of Meyer Schapiro Abroad should not blind us to the grand themes that circulate through these informally composed letters and notebook pages. If the artists and historians of the 19th century had embraced Gothic art and architecture with a fiery passion, in the 20th century it was the art before Gothic — the achievements of the Byzantine, Early Christian, and Romanesque periods — that preoccupied many of the most adventuresome thinkers and creators. Although the fascination with the Romanesque originated deep in the 19th century, there was something about the blunt directness of Romanesque art that proved especially appealing to eyes attuned to the work of Gauguin, Picasso, and Matisse. For Schapiro, the Romanesque had a boldness, maybe even an impetuousness. “This rapidly evolving productiveness in all the arts,” he observed in a letter to Lillian, “the great energy of the builders, and the transmission of the newer ideas over large areas from North France to Spain to Italy or even Syria in a little time, remind one of the history of the modern sciences.” This is a fascinating remark. What Schapiro was finding in the Romanesque was a headstrong experimental spirit, an indifference to received ideas, a desire to discover new forms — and all of this somehow suggested a premodern avant-garde, the excitements of scientific discovery.

Living in Europe in 1926 and 1927, Schapiro was aware that many of the Europeans whom he met did not share his optimistic spirit, and perhaps part of what made him such an appealing figure was his immunity to anything but the most fleeting feelings of disappointment. “About Europe every intelligent man I have spoken to is depressed,” he wrote to Lillian. “This is the end of the world; all culture, & goodness are dying from external economic & political troubles. Science keeps on producing in a blind, mechanical way things intrinsically beautiful but unavailing: there is still a little art, decadent, however —; the hegemony passes to America — There is such certainty about this in the few I have heard, that it is impossible to question, — ” At times, even this man who was bewitched by the wonders of scholarship seemed to find something quixotic about the life of the mind as he saw it pursued in Europe. “I am overwhelmed by the libraries of the world which surely contain 10,000,000 monographs — & the books, stores & quais, & the pages rotting in warehouses — which no search for proposed truth or man’s happiness designed, but the professional practice of printing, broadcasting personal details.” Perhaps it was in response to this nightmare vision of writings rotting in warehouses that Schapiro in his maturity sometimes seemed to prefer thinking and talking to writing and publishing, despite the large number of essays he ultimately produced. Perhaps he wanted to preserve the speculative spirit of those early adventures in Europe. He may have hoped to give even his deepest insights a lightness, a liveliness.

What one feels strongly here, at the beginning of Schapiro’s career, is a mingling of joyousness and exactitude that would characterize his thought to the very end. I cannot say I knew Schapiro, but I did study with him, taking a seminar in Sociology of Art that he offered in the fall of 1971, my senior year in the College. What I remember is what many probably remember, which is the blending of austere discipline and brilliant volubility. When he heard that I was planning to be a painter rather than an art historian, he seemed to think I might not be serious enough for the seminar, observing, “You know that this is a work course.” (I did, for the record, receive an A.) And at the end of one visit to his office, when I was halfway out the door, he noticed that I had left my New York Times on a table and seemed slightly disapproving of my forgetfulness. Yet, what I recall more than anything from those afternoons in the seminar room was the unpredictable range of his remarks, the comments that turned into miniature discourses and left the afternoon’s putative subject far behind. One day he discussed the place of aesthetic judgment in the traditional Jewish home, expatiating on the visual power of the Sabbath table, with its white cloth and its symmetrical arrangement of candles, wine, and bread. Another time, when a student was presenting one of Andy Warhol’s silk-screened self-portraits as part of a seminar report, Schapiro launched into a brilliant psychological analysis of Warhol’s pose, in which the artist’s fingers covered his mouth. (I already had developed a distaste for Warhol’s work, and remember thinking that this was an awful lot of intellectual firepower to squander on an essentially meretricious image.)

The Meyer Schapiro of these early letters was wise beyond his years, with a self-confidence so magnificently unflappable that it can leave a reader smiling with pleasure — and even astonishment. The miracle was that he never lost the avidity that had sent him dashing across Europe in 1926 and 1927. Back in New York he would study and teach and take part in many of the great political and artistic adventures of the midcentury years, a man who cared for both politics and art. He was active in the anti-Communist Left, a founder with Irving Howe and others of the magazine Dissent, and a friend to the abstract expressionists, especially Willem de Kooning and Barnett Newman. He was a pure New York product, at once pragmatic and adventuresome and optimistic, and surely he saw something of those same virtues in the Romanesque artists, those anonymous craftsmen whose work he had fallen in love with as a young man and about whom he would be thinking and lecturing and writing for the rest of his life.