The Columbia sociologist C. Wright Mills (1916-1962) is remembered today as one of postwar America's most controversial thinkers. A Texas-born intellectual, author of the classic study The Power Elite (1956), and a left-leaning critic of Cold War liberalism, his politics were unapologetically oppositional. Informed by an older but still resonant farmer and labor radicalism, they displayed clear progressive and socialistic sympathies sometimes mistaken for Marxism. But Mills was no dialectical materialist. He produced, rather, popular scholarship that above all offered the average American a glimpse into the vast apparatus of interlocking power structures that comprised what President Dwight D. Eisenhower later called the "military-industrial complex."

Mills arrived at Morningside Heights in 1945 as a research associate at Columbia University's Bureau for Applied Social Research (BASR), which was led by Paul F. Lazarsfeld. The bureau was a leader in the emerging field of survey research and Mills quite rightly regarded his appointment as "a hell of a big break for a kid 28 years old." Eventually he moved to the sociology department, where he became a full professor in 1956. Among the cluster of public intellectuals who distinguished Columbia during this era - including Richard Hofstadter, Lionel Trilling, and Jacques Barzun - Mills remains a compelling figure whose scholarship continues to challenge our notions of what it means to live in a democracy that comfortably houses a power elite.

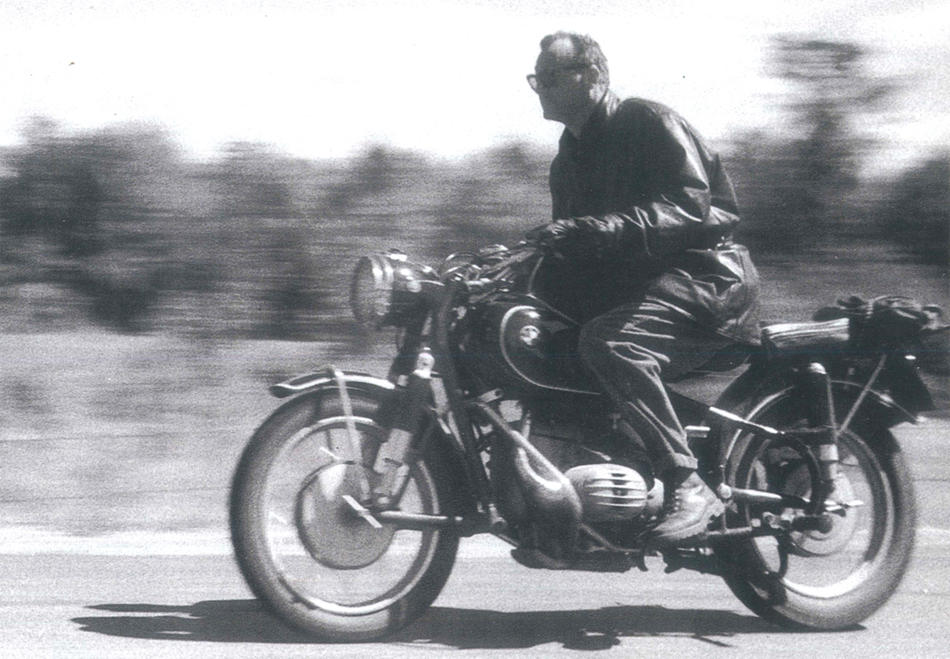

Over the past few years, scholarly interest in Mills has picked up. C. Wright Mills: Letters and Autobiographical Writings (with an introduction by MillsÕs student Dan Wakefield '55CC) appeared in 2000, and late last year came The Politics of Truth: Selected Writings of C. Wright Mills, edited by John H. Summers. Now we have Daniel Geary's Radical Ambition: C. Wright Mills, the Left, and American Social Thought. According to Geary, Mills's controversial writings and rebel reputation have obscured his close connections to the intellectual currents that shaped the social sciences in the 1930s and '40s. The leftist seer on motorcycle, the Texas rustic who urged his East Coast colleagues to drop the academic jargon and "take it big, boy!" and the scourge of Wall Street and the Pentagon, Mills has become a transcendent figure in pop intellectual iconography.

Geary isn't buying the hype. "The origins of his thought," he writes, "lie not in an early involvement in literary, bohemian, political, or journalistic circles, but in a university education in the social sciences." True. As an undergraduate at the University of Texas, Mills was weaned on pragmatism and Chicago School sociology - intellectual traditions that emphasized flexible and variegated approaches to understanding the world. Pursuing a PhD at the University of Wisconsin, he gravitated to Hans Gerth, a German émigré, Weber specialist, and student of Karl Mannheim, one of the century's major social theorists. In Madison, Mills absorbed Mannheim's emphasis on the connection between ideology and environment. And this in turn reinforced his emerging understanding of knowledge as an instrument of practical possibilities affected by class, education, and status. His biting critique of postwar social science's grand theory fetish for universal laws, in other words, had its roots in an older classical sociological lineage.

Like many intellectuals who came of age during the Depression, Mills hoped that America would advance beyond the competitive capitalism implicated in the crash of 1929. But to his disappointment, the new politics appeared more tepid than transformative. Despite its social welfare advances, Keynesian economics substantially sustained the free-market system while liberalism's do-or-die pledge to contain Soviet power contributed to the militarization of American society. In response, Mills posited what he called the "politics of truth," shorthand for a searching and critical reexamination of the nation's values, commitments, and goals. Notwithstanding the suggestive optimism in the phrase, it translated into a frankly dystopian vision of the Modern Age. In a series of important books on contemporary America - The New Men of Power (1948), White Collar (1951), and the aforementioned The Power Elite - Mills maintained that the imperatives of the U.S. consumer-based economy combined with imperial ambitions to constrict freedom of thought and action.

Such a gloomy conclusion was heresy in an academy that rallied around the midcentury claim of Mills's Columbia colleague Daniel Bell '60GSAS that, with fascism defeated and communism contained, the West had reached a benign "end of ideology." Mills dismissed such thinking as sociology for the status quo, for it left precious little intellectual space to construct fresh centers of cultural resistance. Breaking from the guild, he ceased to write within the professional mainstream. Instead, his essays were coveted by such popular periodicals as Harper's and the Saturday Review of Literature. (The London Tribune celebrated Mills as "the true voice of American radicalism.") Read against the backdrop of the broader cultural zeitgeist, his books were distant but discernible cousins to The Catcher in the Rye and The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit.

Mills's independence from the academy raises the question of how far Geary's thesis holds up. He asserts that "a full understanding of [Mills's] ideas and their historical significance has been obscured by a captivating caricature of him as . . . a lone dissident." But with the possible exception of the doctorate-less David Riesman, author of the hugely successful The Lonely Crowd (1950), no other generational peer sociologist wrote as critically or as acutely about the dangers of economic and political power as Mills. Whether he was cultivated or not, a strong streak of occupational alienation and defiance underscored much of his work. As Geary himself notes, Mills's 1952 refusal to continue working on a long-standing BASR project tracking the flow of influence and information in Decatur, Illinois, "marked [his] definitive break with academic sociology as a whole." A number of factors influenced Mills's decision, including his colleagues' refusal to accept what he considered the clear political meaning of the study, namely, that Decatur, and by implication America, was a status-driven, elite-centered society.

In regard to Mills's personal life, all but absent in Radical Ambition, one wonders about the possible connections between his private and professional interests. Married four times to three women, a devotee of organic farming, and a skilled craftsman who built his own house, he approached his life as an ongoing creative process, not to be constricted by convention. Importantly, he pursued scholarship with a similar intentional élan atypical in a peer-review profession. How much of this "man apart" persona was calculated by Mills to accentuate his distance from the ivory tower is debatable. More certain is that some assessment of his regional background seems in order. Born in the South and educated in the Midwest, he stood conspicuously outside the academy's coastal centers of power. To what extent, in other words, did place shape his politics?

Radical Ambition is on surer footing assessing its protagonist's scholarship. The book hews to a logical chronology, moving from Mills's education, early professional years, and major studies to his late-in-the-day turn as a transitional intellectual connecting the Old Left and the New Left. It is in this last section that Geary is most original and most interesting. He persuasively situates Mills within a rich context of circa 1960 transatlantic radicalism commonly critical of both Western capitalism and Eastern communism. This relationship proved imperfect. Mills's pessimistic assessment of labor's ability to effect systemic structural change bothered British thinkers like historian E. P. Thompson, who rejected the implied alternative assumption that elite minds - the thinking class - could best advance the interests of the working class. Weren't the eggheads just another presumptive power elite?

By this time, Mills had traded professorial reflection for a new persona: the sociologist as action intellectual. In this final phase, he rapidly produced three polemics - The Causes of World War Three (1958), Listen, Yankee: The Revolution in Cuba (1960), and the posthumously published The Marxists (1962) - books unabashedly designed to reach a popular international readership struggling to make sense of the nuclear brinksmanship and neoimperialism of the times. Having given up on labor's potential to tame capitalism, and skeptical of the New LeftÕs power to reform America, Mills looked with optimism to Castro's Cuba as a Latin "third camp" in a bipolar world. In an emotionally charged essay in the December 1960 Harper's, he made the case for the Cuban Revolution - curiously writing as a Cuban revolutionary. Referring to "we Cubans," Mills welcomed the end of American influence in Havana: "Well, that's over, Yankee, we've made laws and we're sticking to them, with guns in our hands. Our sisters are not going to be whores for Yankees any more." The possibilities of Latin American revolutions proved to be Mills's final political investment; he died less than a year after the invasion of the Bay of Pigs.

Much like John Kennedy, his bête noir in the Cuba drama, Mills's reputation benefited from an early exit. The welter of issues that consumed the 1960s but had clear roots in the '40s and '50s - race, gender, and the counterculture - were never a part of his oeuvre. When searching fruitlessly for democratic structures of oppositional power, he inexplicably overlooked the civil rights movement, perhaps the single most successful popular source of oppositional power in the American Century. It simply wasn't on his radar. Gone at 45, he left behind a parcel of provocative books and a contested legacy, which we continue to wrestle with today. Perhaps Geary is right, and that what we need to know about Mills is how his rebel critic reputation has obscured his connections with a broader postwar left. But this tells only part of the story. As interesting is the incredible resiliency of the Mills Myth. For this says as much about Mills's radical ambition as it does about our contemporary need to believe that it is possible to create a civic culture that is fundamentally open, just, and democratic - to believe, that is, in the "politics of truth."