Forty years ago this spring — on the morning of April 24, 1968, to be exact — some 200 students broke into Low Library and occupied the office of University president Grayson Kirk. Drawers were rifled, files unearthed, objets fondled, cigars smoked.

One of the students in the crowd had come to the Battle of Columbia with a pen in his hand. Jerry Avorn ’69CC was a reporter for the Spectator. “I kept asking myself, ‘Am I here as a demonstrator?’” Avorn said the other day from his office at Harvard Medical School. “‘Am I here as a journalist? Am I here as a sympathizer? What am I doing here?’ Actually, it was that there was a need to get the correct story out.”

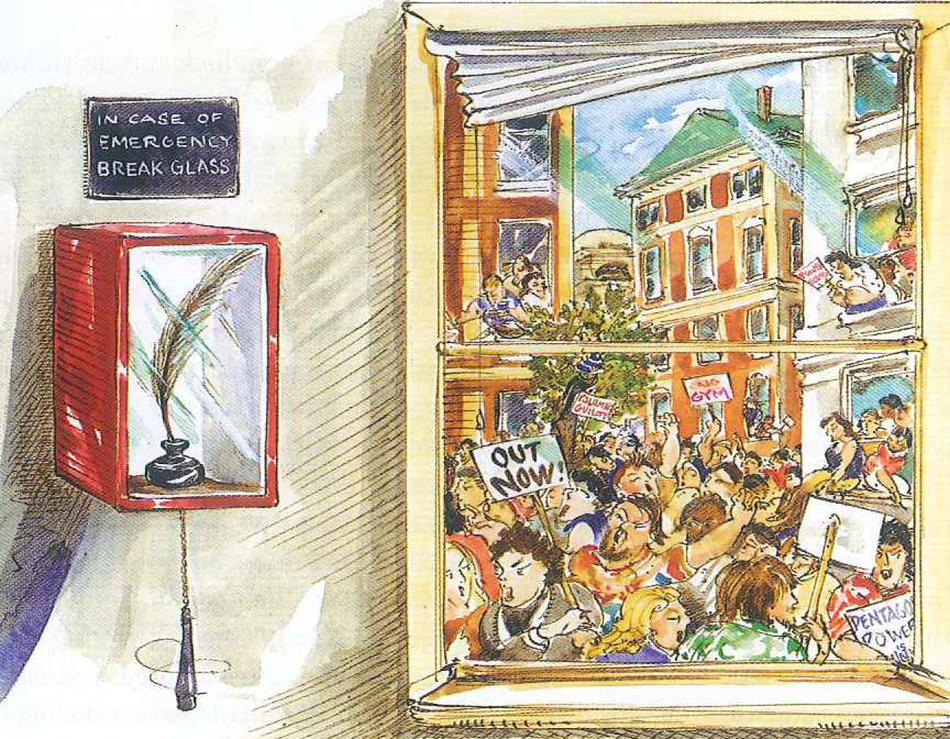

Avorn and his Spectator colleagues had found news coverage of the struggle between students and the Columbia administration to be wanting in accuracy, not least at the New York Times, whose publisher, Arthur Hays Sulzberger, was a Columbia trustee. Student anger — over the University’s construction of a racially divisive gym in Morningside Park, its links to a Pentagon think tank, its authoritarian power structure — had reached the breaking point; there was a sense that the story, which seemed to sprout a new head every minute, could not be left in the hands of the mainstream press. And so the Spectator writers, none of them older than 22, set out to tell what was really happening.

That was no simple matter in 1968. Even without drugs, reality was pretty distorted. By late April, Americans had seen the Tet offensive, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., rioting in U.S. cities, and still more devastation in Vietnam. Add to that the big questions swirling in the heads of smart college kids and things get murky fast. What is truth? What is reality? What is objectivity?

Undaunted by metaphysical distractions, the Spec staff set to work. Avorn was the principal writer on an all-star team that included a future Pulitzer Prize winner (Paul Starr ’70CC) and the future international editor of Fortune magazine (Robert Friedman ’69CC). The reporters fanned out over the campus to capture events as they unfolded. Then, with a small publishing advance and a lot of adrenaline, they hunkered down for the summer in the old Spec offices in Ferris Booth Hall. And wrote.

The result of their labors was Up Against the Ivy Wall: A History of the Columbia Crisis, a 300-page book that stands as the definitive account of the uprising. Shrewd and sophisticated, the work is notable for its accomplished prose; its mastery of the intricate web of groups, committees, and personalities involved in the conflict; and for the sober critical distance that its authors managed to maintain in the heat of battle.

Even the reporters’ distaste for Grayson Kirk (for they were still students) is refined by the sureness of the writing: Kirk’s offices had de facto been off-limits for students of the University, except under extraordinary circumstances. Only a handful of these students had ever, as individuals, even seen the President face to face. It is improbable that any had ever spoken to him. If they had it is highly unlikely that he had answered them. As Eric Bentley once said of Grayson Kirk, “He hasn’t spoken to anyone under 30 since he was under 30.”

With Kirk’s offices no longer off-limits, and with other buildings now under student control, Avorn and his colleagues were able to literally get inside the story, trading conventional arm’s-length reportage for the flesh-and-blood portrayals of New Journalism. The first draft of history was at hand.

While the young reporters chased after objective reality, another writer in Kirk’s office that morning was viewing the spectacle through a slightly different lens.

Jim Kunen’70CC had been fooling with the office copying machine when word reached Low Library at 8:30 a.m. that the cops were coming. The doors were barricaded, so most of the students clambered out the windows. But Kunen, a literary man who was reading Lord Jim for class, stayed put. In the novel, the protagonist, a first mate on a ship, abandons the vessel and its passengers during an accident — and is later sorry he did.

Kunen spent much of the week in Low, until he was carried out by the police on April 30. The next day, he got a call from a friend who asked him if he would like to write about his experience for the Harvard Crimson. Kunen composed a piece in diary form, which the Crimson ran.

“The next thing I knew,” Kunen recalled recently, “my roommate ran up to me and said, ‘Kunen, you’re famous!’ And I said, ‘What do you mean?’ And he said that my friend at Harvard had called to say that some guy named Clay Felker bought the rights to my article for New York magazine and that it was going to be on the stands the next day.”

The article quickly led to a book contract with Random House and a movie deal with producer Irwin Winkler. The book, titled The Strawberry Statement: Notes of a College Revolutionary, was an instant success. Praise poured in from the New York Times, Newsweek, and Kurt Vonnegut. At 19, Jim Kunen was a literary star.

Like Up Against the Ivy Wall, The Strawberry Statement is a marvel of undergrad precociousness, and Kunen’s voice rings with poignant familiarity. He’s the brainy, cynical, sweet-natured kid lurking on the edge of the action, too suspicious of mobs to fully join any movement, too ironically detached to chant slogans, but dead serious about social justice, and about baseball, too. He’s Holden Caulfield with hair:

Inside we rush up to Kirk’s office and someone breaks the lock. I am not at all enthusiastic about this and suggest that perhaps we ought to break up all the Ming Dynasty art that’s on display while we’re at it. A kid turns on me and says in a really ugly way that the exit is right over there. I reply that I am staying, but that I am not a sheep and he is.

The book was just the beginning of Kunen’s own strange dealings with the frayed fabric of reality. In a metafictional twist worthy of Vonnegut or Robert Coover, Kunen was asked to play a small role in the movie version of The Strawberry Statement, which was being filmed in San Francisco. When he arrived on location from the airport, Kunen was amazed by what he saw: Assembled under the night sky were dozens of fire engines, police cars, and National Guard trucks. It looked like Armageddon, but in fact it was the re-creation of the climactic bust.

“It’s kind of like knocking over a quart of milk,” Kunen said, “and the next thing you know, the entire city is flooded.” The movie, which was scripted by Israel Horovitz, went on to win the Prix du Jury at Cannes in 1970.

The book has remained in print and continues to be discovered by new readers (and, interestingly, is a big hit in Japan), while Up Against the Ivy Wall still surfaces in college journalism courses. Jerry Avorn hopes to make Ivy Wall available to a wider audience, either through a reissue or the Internet.

As the veterans of Columbia ’68 gather at events on and off campus to look back on a convoluted history, these two remarkable volumes stand as unwavering reference points, their insights and observations uncorrupted by any long-range retrospection.

“When history is written up too currently,” a trustee comments in The Strawberry Statement, “there are pros and cons regarding its merits.”

With these books, mostly pros.