Dov Scheindlin

Then: Professional violist

Now: SIPA student

For thirty years, I’ve made my living as a professional violist. I studied at Juilliard and have played all over the world, but I’ve spent most of my career in New York, where I’m a member of the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra.

When COVID-19 hit, the music world shut down. I started to get nervous about the future and wondered what I would do if I wasn’t playing the viola. I knew that I wanted to make the world a better place and that there’s a limit to what music can accomplish. Almost on a lark, I decided to apply to SIPA, which is just a few blocks away from where I live.

I’m now finishing my first year in the master of international affairs program, concentrating in economic and political development. It’s been liberating to think about the world in such a different way and invigorating to be around so many idealistic young people. It’s honestly kind of a rebirth.

I’m not sure yet what I want to pursue after graduation, but I know that I want to help bring prosperity and agency to people who need it. I’m in a very lucky position: music has come roaring back, so I’ve been able to juggle my two roles while I figure out my next steps. I’ve had a rich and varied career in music, but I’m having such a great time discovering this new side of myself.

Faith Grady

Then: Makeup artist

Now: GS student

Before the pandemic, I spent four years working as a makeup artist in Los Angeles — first as a beauty stylist at Nordstrom and then freelancing in the advertising industry and for celebrity clients. Some especially memorable projects were assisting on a music video with singer-songwriter Gracie Abrams and working on promotional campaigns for Netflix and Hulu.

At the start of the pandemic, the entire beauty industry came to a standstill. To fill the time, I enrolled in community college, thinking that I might eventually transition to the business side of the industry. As soon as I was back in a classroom, I remembered how much I loved learning. I had always been in honors classes but was so burned-out by the end of high school that I went straight to a trade school.

I started thinking more seriously about a four-year degree and looking beyond the beauty industry. Some software-engineering friends introduced me to the idea of computer science, and I taught myself the basics and found that I loved it. I applied to five East Coast schools, and Columbia felt most like home. I’m now finishing my first year, and it’s been an unexpected but incredible experience.

Tristen Kim

Then: Actor

Now: Columbia Nursing student

I started acting when I was a college student in South Korea, studying theater, French, and Japanese. I was cast in a small community-theater production, and found that I loved it. That play ended up on the Korean equivalent of Broadway, which led to television roles, as well as short films and commercials across Asia. Like many young actors, I decided to drop out of college and move to Los Angeles to try to make it in Hollywood.

Acting has truly been a source of healing in my life; it’s gotten me through difficult times and helped me overcome traumatic experiences in my past. So when I started to think about a career that would complement acting, nursing seemed like a natural fit. I was committed to continuing my artistic goals but also wanted a stable job that allowed me to serve people. I finished my undergraduate degree in neuroscience, completed my prerequisites at USC, and then applied to Columbia’s RN program.

I’ve spent a lot of time working in the hospitality industry, and I think that experience, as well as my acting, will be helpful as I start my nursing career. Nurses have the most interactions with patients; they’re the ones going room to room to check if things are OK. I thrive on those personal interactions, even in fast-paced and stressful environments.

Will Savage ’19CC

Then: Minor-league baseball player

Now: VP&S student

I was drafted in 2016 by the Detroit Tigers and spent four years playing in the minor leagues. I grew up in New York City, so it was eye-opening to live in different parts of the country, staying with host families and forming friendships with people of very different backgrounds. Getting to play baseball at that level was a dream come true. But it’s not easy. Players often leave their families as teenagers and have to deal with the daily threat of losing their jobs. I’ll always remember how deftly my teammates handled that pressure.

When the minor-league season was canceled because of COVID, it felt like a natural time to apply to medical school. I also got my undergraduate degree from Columbia, so I was returning to a familiar place. But I think that my time away was really valuable. I hope that it will make me a better doctor.

Catherine Jennings ’19GS

Then: Middle-school science teacher

Now: VP&S student

I spent eleven years teaching middle-school science, first at a public school in Knoxville, Tennessee, and then at a private school in Brooklyn. I got into education because it felt both familiar and important — my mother, an exceptional educator, was actually my seventh-grade science teacher. I didn’t know of a lot of women doctors, or women going to medical school, so the representation wasn’t there for me.

I loved teaching, but after a while I started to feel stagnant. Medicine was always in the back of my mind, but by then I was in my mid-thirties, and I felt too old to go back to school. Eventually, I realized that I was the only one standing in my way, and that starting over to pursue my passion was a powerful message I could give my students.

I have no regrets about my long teaching career. It has made me a better student, because I do what I would tell my own students to do: I advocate for myself and use all the resources available to me. I’m also certain that it will make me a better doctor. I’m entering my fourth year of medical school and planning to go into obstetrics and gynecology. I know that I’m going to serve patients from all walks of life, with varying degrees of health literacy and knowledge about their own bodies, and I really want to empower them to understand and take control of their health. My time as a teacher has prepared me to meet each patient where they’re at.

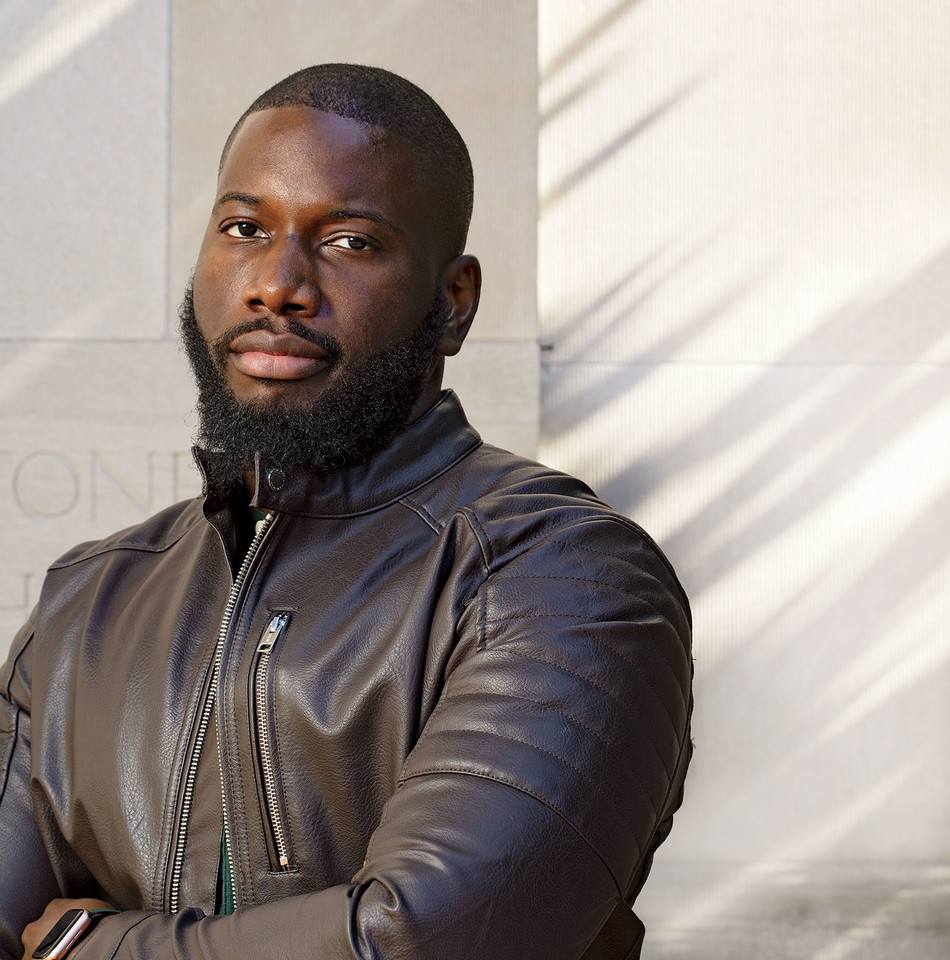

Kaelo Justin Iyizoba

Then: Pharmacist

Now: SOA film student

In Nigeria, where I grew up, there’s a lot of societal and familial pressure to find a practical career — something like law or medicine. My sister was a pharmacist, so I decided to follow in her footsteps. I studied pharmacy for five years, did an internship, and then practiced for a year. It was OK, but my heart wasn’t in it. I wanted to do something more creative.

When I wasn’t studying, I was watching movies or television. I started looking into coursework that would lead to a job in the entertainment industry and came across Columbia’s film program at the School of the Arts. I didn’t think that I had much of a chance: my journey to film school was not straightforward, and a program of Columbia’s caliber felt out of reach. But I really wanted to try.

I’m now in my second year of the MFA program, and with each passing day, my voice as a filmmaker grows. The film industry in Lagos — called Nollywood — has exploded in recent years, but the focus is on quantity over quality. I want to tell authentic stories that amplify voices from Nigeria and the rest of the continent and that will also travel far beyond them.

A lot of my classmates came to Columbia after many years of studying art. I had none of that experience, but I actually think that’s to my advantage. I take things at face value, without overintellectualizing them. I don’t look at things through the traditional lens.

Jarrell Daniels ’22GS

Then: Incarcerated

Now: GS graduate

Graduating from Columbia — with a double major in African-American studies and sociology — is something that I never could have imagined. I plan to go on to law school and eventually run for public office, with the hope of driving institutional and justice-system reform. I know firsthand how difficult it can be to survive prison and succeed afterward.

I was arrested and charged in a forty-one-count gang conspiracy case with nine of my friends when I was eighteen, and I was sentenced to six years in prison. While serving my final ninety days at the Queensboro Correctional Facility, I saw a flier for a new program being offered in the prison called Inside Criminal Justice — a semester-long seminar, cosponsored by Columbia’s Center for Justice, that brings together incarcerated people and prosecutors. I had never taken a college course, but I saw it as a way to redeem myself and prepare to return to society. I wanted people in power to see that my life wasn’t disposable.

I was so motivated to get a degree that I actually returned to the same prison after my release to complete the course. I spent a year in community college and then transferred to the School of General Studies in 2019. That same year, I founded the Justice Ambassadors Youth Council — an eight-week program designed to bring justice-involved youth together with city officials to identify and discuss community challenges and then co-develop policy proposals aimed at addressing them.

It’s almost impossible to thrive after leaving prison. I know that my story is unusual — I’m one of seventy million felons, most of whom don’t have access to institutions like Columbia or its resources. As a Black man with a criminal record, I have two strikes against me. I see education as the only equalizing factor, the only way to prevent that third strike.

Reed Kessler

Then: Olympic equestrian

Now: SIPA and GS student

I’ve been riding horses competitively since I was a child. I grew up riding with my family, and my godmother, Katie Prudent, is one of the most decorated female equestrians of all time. I was lucky to have a few big career highlights at a young age. I won the US national championship in show jumping in 2012, when I was seventeen. That same year, I became the youngest equestrian athlete to compete at the Olympic Games.

I made wonderful memories competing, but I reached a point where I didn’t feel as fulfilled and I wanted to go back to school. Alongside my athletic career, I’m an ambassador for JustWorld International, an organization that partners with local NGOs to provide educational opportunities to underprivileged children. That experience sparked my interest in human rights and foreign policy, which led me to Columbia.

As a slightly older student, the fast track to a bachelor’s and a master’s in the SIPA/GS dual-degree program was incredibly appealing to me. I’m concentrating in international security policy and am currently interning at the United States Mission to the United Nations. I’m interested in a career in either foreign or civil service at the State Department or in peace operations at the UN.

My athletic career was instrumental in getting me where I am today, and I know it will continue to prepare me for what lies ahead. I learned discipline, perseverance, patience, and strategic planning — all skills that make for a successful student and civil servant.

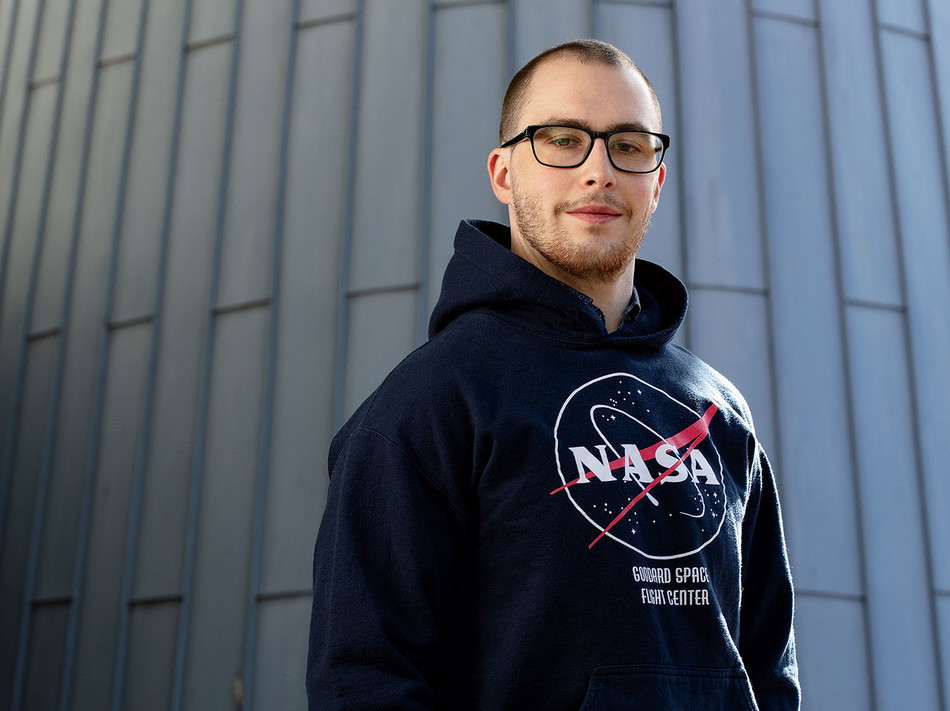

Daniel Munden

Then: NASA engineer

Now: Columbia Law student

I spent a little over four years working at NASA as a structural analyst, which means that I helped to design, analyze, and test spacecraft to ensure that they wouldn’t fail during launch and operation. I designed parts of the Orion — a spacecraft that will eventually be used in the Artemis mission to return astronauts to the moon — and I developed mechanical specifications for the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope.

It was thrilling to have that kind of hands-on experience. But working in the DC area, I became aware of how much impact the law and legislative process has on high-level decision-making at places like NASA. I decided to apply to law school because I wanted to be a part of that, to add that to my skill set.

I haven’t decided yet what I want to do when I graduate; eventually, I might return to NASA in a different capacity. For now, I’m getting used to learning in a different way, and to a whole lot more reading.

Danica Selem

Then: Architect

Now: SOA theater student

My father was a theater director from Split, a historic city on the Dalmatian coast of Croatia. All my early memories are from the theater — doing my homework in the wings and staying up late to watch rehearsals. I was always interested in the process of making theater, but I wanted to forge my own path.

I decided to study architecture, which combined many of the things I loved: art and art history, design, politics, and social science. I did my undergraduate studies in Croatia, then came to the US to earn an MA at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

While I was in graduate school, I realized that I viscerally missed working with bodies and movement in real spaces. I started a research and performance group called Bodies Intersect Buildings, which explores how architecture shapes our physical, social, and emotional behaviors. And I taught architecture at Cornell, where I designed two elective seminars on the themes of body and space, and created performances in collaboration with students from the music department.

I realized that, despite my best efforts, I was getting back to my theatrical roots. A friend asked me to assist with a play she was directing, and it felt like coming home. I’m now finishing my first year in Columbia’s MFA program in theater directing, and I couldn’t be happier. I just directed a beautiful play, The Woman and the Banana Tree, written by a classmate, and I am working on several other projects. I’m in love with the live aspect of theater — the fact that so many people have to align to make a singular event happen — which feels especially important in this moment.

Maher Benham ’75GSAS, ’22NRS

Then: Modern dancer

Now: Nurse practitioner

I started dancing when I was four years old, and it’s been the through line of most of my life. I trained with Martha Graham, whom I consider my mentor and spiritual mother, and I still teach her dance techniques to this day. I’ve traveled the world, studying dance traditions — including as doctoral research for a PhD program in cultural anthropology that I completed at Columbia — and founded my own modern troupe, the Coyote Dancers.

In 2003, I started a dance, yoga, and music academy called the Hummingbirds School, geared toward people with special needs. I was inspired by my nephew, who was born prematurely with cerebral palsy. When he was small, he used to come to my dance classes and move to the music in his wheelchair.

Nursing was something that had always interested me, and my work with dancers with special needs made me consider it more seriously. Making such a big change wasn’t easy; I’d never studied science before and had to take two years of prerequisites before even applying. When I started the program, I thought that I might not be taken seriously. But everyone at Columbia was so respectful — both faculty and students.

Nursing and dance sound like two totally different things, but I don’t think that they are. Exercise, yoga, and meditation can help people live healthier lives and prevent disease. And I believe fundamentally that art heals — physically, emotionally, and spiritually. When the audience sees you leap, they feel like they can surmount all the obstacles in their lives. When I bring dancers into a nursing home full of patients suffering from dementia, I start to see a light in their eyes. My mission is to combine the two sides of my life in a meaningful way, and Columbia has prepared me to do exactly that.