A person of vast international stature, Madeleine Albright ’76GSAS, ’95HON cuts herself down to size to put an audience at ease. The most powerful woman in the world during her years as Bill Clinton’s secretary of state, Albright routinely introduces her speeches with a comment on her diminutive height, her makeup kit, her wardrobe, or her collection of patriotic jewelry pins. On Morningside Heights, where she has been seen more and more lately, she tends to make light of her unusually long career as a Columbia graduate student. At the World Leaders Forum last fall, she told the audience about the thirteen years she took to earn a Columbia PhD while she was raising her family. “I was constantly afraid that the registrar would realize that I had been here too long,” she joked. “I kept having babies to get extensions.”

The lightness gives way to gravity, though, when she gets to the subject at hand, be it the presence or absence of women in international politics, the danger of nuclear weapons in North Korea, the breakdown of diplomacy, or the war in Iraq. The audience gets a sense of the forthrightness with which she made her case — and the case of the United States — during her years as ambassador to the United Nations and as secretary of state.

Madeleine Korbel Albright was born in Prague in 1937. Her family fled to England in 1938 to escape the Nazis and, having returned to Czechoslovakia after the war, to the US in 1948 to escape the communists. Albright earned her BA in political science from Wellesley College in 1959 and studied at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University before beginning her work at Columbia. She received her certificate from Columbia’s Russian Institute in 1968, her MA in 1968, and her PhD in public service and government in 1976. (Her dissertation was titled “The Role of the Press in Political Change: Czechoslovakia, 1968.”) Her mentor was Zbigniew Brzezinski, who left Columbia’s faculty in 1976 to become Jimmy Carter’s national security advisor. After working with Senator Edmund Muskie as chief legislative assistant from 1976 to 1978, Albright rejoined Brzezinski as a member of the National Security Council and White House staffs. She taught on the faculty of Georgetown University from 1982 until 1992.

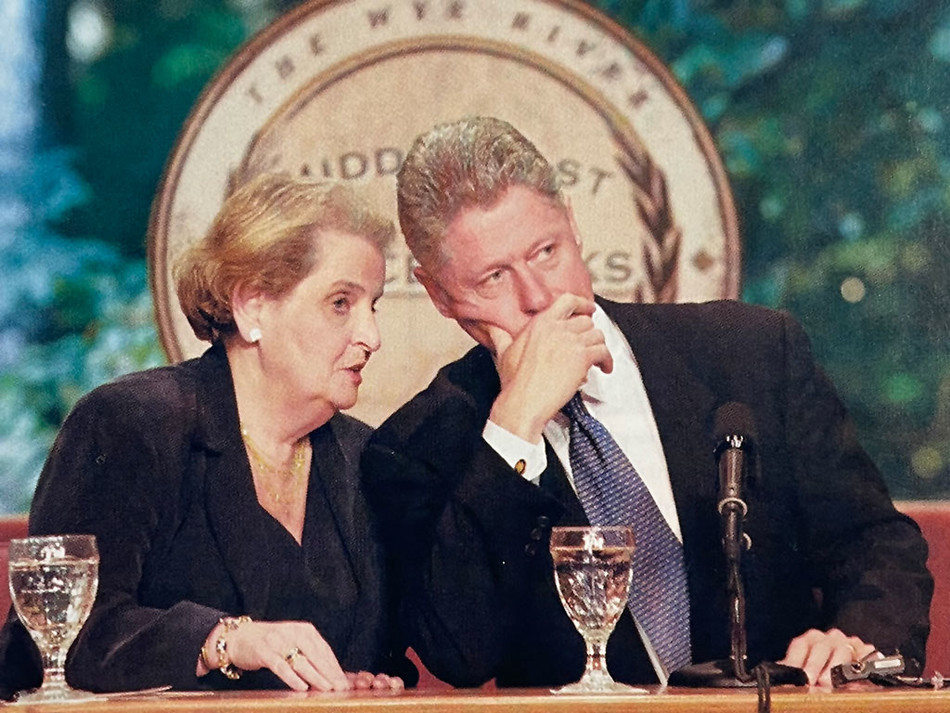

Albright served as the US ambassador to the United Nations during Bill Clinton’s first term, and as the country’s first female secretary of state during his second, from 1997 to 2001. She is now a principal of the Albright Group, a global strategy firm in Washington.

Columbia awarded Albright an honorary doctor of laws in 1995. In 2003 SIPA honored her with the Andrew Wellington Cordier Award for Distinguished Public Service for her “strong commitment to public service and to developing constructive US policies abroad.”

In September she joined Columbia as the first Visiting Saltzman Fellow at the Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies. Albright will lecture and continue her research on democratization as well as the role of women in international affairs.

Between appearances on campus last fall, Albright spoke briefly with Columbia Magazine about the war in Iraq.

French President Jacques Chirac said that the war in Iraq is a Pandora’s box that “I don’t think we can close.” Putting off for a minute the pros and cons of having gone to war, can you comment on where the war is right now and what President Bush needs to think about — fast.

I’m not sure that I’d use the term Pandora’s box, but in nondiplomatic terms, I’d say it’s a mess. This was a war of choice, not of necessity; but getting it right is a necessity and no longer a choice. No matter how we got there, the war has the potential of creating greater mayhem not only in Iraq but in the region.

While I never thought there was a connection between Al Qaeda and Saddam Hussein, Iraq, as a result of the chaos, has become a breeding ground a recruiting ground for terrorists.

Economically, Iraq is not being reconstructed fast enough to provide jobs, and that undermines stability. So does the constant sabotage of the oil fields. Those are very difficult problems. But what has to happen first is that we have to stop digging the hole deeper. We’re still digging.

The Iraqis are not yet ready to defend themselves; they need the Americans to do that. At the same time the Americans are drawing fire to themselves and to ordinary Iraqis. So there’s a terrible paradox because there’s nobody to take America’s place.

Should we have left the Iraqi army at least partly intact?

We definitely should have left the army at least partly intact. One, because we need it. Two, because Saddam’s former soldiers are out loose. It was a mistake and another indication that there was no postconflict planning — or that planning was very badly done. This planning work belonged in the State Department. It went to the Pentagon. I was stunned by the extent to which the administration did not consider trying to get an international organization involved.

Our military has been brilliant, and we all owe those soldiers a debt of gratitude. But we need to use the United Nations in some way. Unfortunately there was no plan to do so because it seemed everybody in the administration disdained the UN. The January elections, while necessary, cannot be a total success for security reasons alone.

Why was the postwar planning so poor in your view?

I think that there was misinterpretation of 9/11 and what it meant. The people who ultimately surrounded current President Bush had the idea of attacking Iraq and toppling Saddam Hussein all along. The reasons for this are still relatively unclear, but they were determined and they piggybacked their plan onto September 11. For me, the most serious problem is that George Bush now believes what he says. There seems to be a serious disconnect between the reality on the ground and what the administration is telling the American people is going on.

Before the November election there was debate on whether we’re safer now than we were immediately after September 11, 2001. What is your view?

I think we’re less safe. It happened when we took our eye off the ball in Afghanistan after having made so much out of the need to capture Osama bin Laden. But by not capturing him, and now not knowing where he is, we’ve facilitated the creation of copycats like al Zarqawi. The job in Afghanistan is far from finished. The Taliban is resurging. The warlords are regrouping.

On the other hand, big efforts made in homeland security have improved safety of airports and planes. But I don’t think our ports and trains are any safer.

The question is this: Are we capturing more terrorists or creating more terrorists? I’m afraid there has been an incremental growth in the number of terrorists both in Iraq and worldwide.

What concerns me most of all is that the international organizations, alliances, and relationships we’ve had in place since the end of the Cold War have broken down. It’s difficult to figure out what levers and mechanisms can control the many areas of the world that are out of control. Threats are coming from a variety of places that had not really threatened us before. There’s kind of a devil’s marriage between the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and their availability on the one hand, and on the other, the shadowy groups that operate in a transnational atmosphere without real control by any government, and therefore are very difficult to get at.

If we took our eye off Afghanistan did we also take our eye off Iran and North Korea?

Absolutely. We took our eye off North Korea and Iran while we called them part of the axis of evil and put them in the same box as Iraq. North Korea is now much more nuclear-capable as a result of what’s happened in the last three or four years. In fact, we are concerned that the North Koreans have six to eight nuclear weapons.

But we have to be realistic about what is happening. If you want to talk about weapons of mass destruction and nuclear proliferation, there is a lot of work to be done internationally on the Nonproliferation Treaty, which is a very good vehicle if it works properly, to get some conventions to limit fissile material.

When Colin Powell, who was chairman of the Joint Chiefs, was reluctant to involve the US military in Sarajevo, as ambassador to the United Nations you famously said to him, “What are you saving this superb military for if we can’t use it?” Obviously you’re not opposed in principle to using force. In the case of Iraq, do you think there was a single fork in the road at which the administration took a wrong turn? Was there a point where we shifted our emphasis away from protecting the US?

Preemption has always been a potential tool for any country. I think that we have weakened our case in Iraq because for preemptive to work, we need solid intelligence. Without it, we undermine our case. In other words, intelligence is the Achilles’ heel of preemption.

So yes, there was a fork in the road. It was in November 2001 when President Bush asked Donald Rumsfeld “what kind of a war plan” he had for Iraq, a moment Bob Woodward describes as the beginning of his book Plan of Attack. Clearly there had already been some preparation by various outside people who were ready to push the Iraq issue. The wrong turn came when it was decided to go ahead to Iraq no matter what Hans Blix and the inspectors were saying — no matter what the rest of the world was saying. That not only took the emphasis away from Afghanistan, it also influenced the way the allies and the UN felt about us.

Kofi Annan said that the war “was not in conformity with the UN charter from our point of view, and from the charter point of view it was illegal.” Was it illegal?

I have a problem with this because the UN also said in 1999 that the Kosovo war was illegal since it didn’t have Security Council support — although in that case we had NATO backing. Still, it doesn’t get us anywhere to talk about whether it was illegal or not. The problem is that the war had no international support. This is the hard part. I can say this about Kosovo: we did every bit of diplomatic work because it was evident that our UN resolution would get vetoed. The Russians made it very clear to me that they would veto it, so we worked on NATO and had the support of nineteen countries. I don’t think this administration did its diplomatic work, and as a result they did not go in with the backing of a solid alliance. They had an ad hoc coalition, which is a very difficult way of getting international community support for something.

We are much better off if we do what we do in partnership with other countries. That is not the direction in which we are going right now, and that’s what troubles me, because I believe that the ultimate solution to military conflict, economic development, disease, and poverty requires us to operate multilaterally.

I have a chapter in Madam Secretary about how we spent practically every Security Council meeting trying to get Saddam Hussein to comply with the demands of the weapons inspectors. I believe today that had we given the inspectors more time, the pressure might have been on France and Germany—and not on us. What a difference that could have made.

In her 2003 autobiography, Madam Secretary, Albright writes: “Getting my PhD was the hardest task I have ever faced on my own. It took thirteen years. I began when [my daughters] Anne and Alice were barely out of their cribs. When I finished, they were in high school. In between they taunted me, saying they shouldn’t have to finish their homework if I couldn’t finish mine.”

Her Columbia career began in the summer of 1963. She and her family moved from Washington, DC to Long Island, where Albright’s then husband, Joseph Medill Albright, had been called to work at the family-owned Newsday newspaper. In the following excerpt from Madam Secretary, she describes the great promise of that period of her life.

Our move there also proved beneficial to my academic career. I was able to continue my graduate work at Columbia University. In addition to working toward my PhD, I decided to try to obtain a certificate from the university’s Russian Institute, considered the finest in the country. This meant I had to take even more courses, so I drove into town three days a week. The rest of the time I spent being a Long Island wife, mother, and tamer of an overgrown garden. With help I made it work. […]

My work at Columbia was demanding, and I often wondered why I had set such a hard course for myself. The answer was that I found it exhilarating. There couldn’t have been a better time to be doing Soviet Studies. The 1962 Cuban missile crisis had demonstrated the life-and-death stakes involved in trying to understand the mysteries of the Soviet system, and I had the best professors with whom to learn. The faculty was a Who’s Who in Communist studies — Seweryn Bialer, Alexander Dallin, John Hazard, Donald Zagoria, and Zbigniew Brzezinski, who would later become President Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor, and my boss.

I met Brzezinski when, as a young Harvard professor, he had come to give a lecture at Wellesley. In the interim he had published The Soviet Bloc, a perceptive analysis of how Stalin had put together his empire. He was still only in his mid-thirties but was already being quoted everywhere and was increasingly visible in policy circles. I thought it was essential to get into a seminar he was offering on comparative Communism, itself a novel idea. With all respect to my other former professors, I judged it the best course I took in graduate school. The professor was challenging, the material totally new, and the students all thought they were the best. Brzezinski assigned lengthy readings in Russian without questioning our ability to understand them. Because he was a good friend of my friends the Gardners and I was older than most students, I was able to see his human side. To most students, however, he seemed unapproachable. He was brilliant, did not put up with blather, and while he spoke with a Polish accent, he did so in perfect, clear paragraphs. Even at this time there was little doubt he was going to play an important role in US foreign policy.

On the first day Brzezinski asked for a volunteer to be the first to deliver an oral report. Silence. We all knew that whoever was first would have less time to prepare and with no examples from which to profit. More silence. The smart thing was to wait, even if Brzezinski grew impatient. My hand shot up. Whether father or professor, I had to please. I’m not sure Brzezinski appreciate my “sacrifice,” but I never forgot it, and today there is a special place in my heart for any student of mine willing to do that first report.

At semester’s end I turned in my paper comparing how nationalism and Communism had developed in Yugoslavia and Vietnam, slipping it under Brzezinski’s locked office door with a note asking him to send me my grade. Dread hit me the moment the note was out of sight — the same dread that would strike many times in subsequent years when I worked for him in the White House: how had I spelled his name? “B-r-z-e-z…” or, God forbid, “B-r-e-z”? I’ve still got the note, which remained attached to my paper when I got it back. Brzezinski had given me an A minus, and I had spelled his name correctly.

Excerpt reprinted with permission from Madam Secretary: A Memoir by Madeleine Albright (Miramax Books), copyright 2003 Madeleine Albright.