Tenement Museum President Annie Polland Opens Doors to the Immigrant Past

On a sunny Wednesday afternoon on the Lower East Side, in front of the nineteenth-century brick tenements at numbers 97 and 103 Orchard Street, schoolchildren, tourists, and an office worker on lunch break gather on the sidewalk. They have all come to visit the Tenement Museum, which since 1988 has been telling the stories of the working families, most of them immigrants, who once lived in these buildings. In a moment, the museum’s tour guides will lead guests through the doors, up the dark, narrow staircases, and into small dwellings containing meticulously curated period furnishings (beds, basins, antique sewing machines), objects (thimbles, scissors), and heirlooms (books, framed photographs). Here, in these tiny, cramped spaces, Jewish, Italian, German, Greek, Irish, Chinese, Puerto Rican, and other families established footholds in the city.

“There’s a dynamism here,” says Tenement Museum president Annie Polland ’04GSAS. “Standing in these rooms, you can connect the dots between history, people, primary sources, and objects, and between the past and the present.” Using archival records, letters, interviews, and photographs, the museum’s historians have interpreted the living conditions of tenants in a period spanning the 1860s to the 1980s.

“You’re hearing family stories,” Polland says, “but you’re also hearing about moments of history that you thought you knew — the Draft Riot of 1863, the Panic of 1873, the kosher-meat boycott of 1902 — but which you are now seeing through the perspective of people who could have been your grandparents or great-grandparents. What do families do in adverse situations? How do they cope? People relate to that today, regardless of their background.”

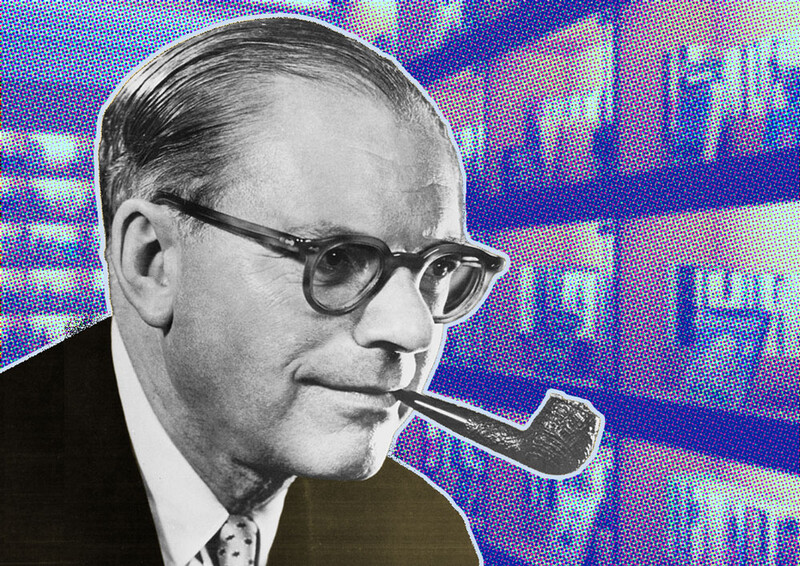

Polland arrived in New York in 1996 to get her PhD in Jewish history at Columbia. For her oral exams she had to read all eighteen volumes of A Social and Religious History of the Jews, by Columbia historian Salo Wittmayer Baron ’64HON, who founded the field of Jewish studies in the US.

Needing a job, Polland heard about Big Onion Walking Tours, founded by Seth Kamil ’24GSAS and Edward O’Donnell ’95GSAS. Big Onion hired graduate students to lead historical walking tours of New York neighborhoods, and Polland, who grew up in Milwaukee, applied. She got what would be a destiny-shaping gig: leading a walking tour of the Jewish Lower East Side. The tour started at the Tenement Museum.

Polland recalls how nervous she was before her first tour and how relieved she’d been when she emerged from the F train at Delancey Street to find that it was raining. “I thought, ‘Oh, good, maybe it’ll be canceled.’ But then I turned the corner and saw all these bobbing umbrellas.” So Polland did the tour — and loved it.

“People were so excited to learn,” she says. “They brought pieces of paper with addresses where their great-grandparents had lived. They might have been from Texas or Ohio, but they felt a direct connection to the neighborhood.”

Upon graduating, Polland worked at the museum at the Eldridge Street Synagogue, built in 1887 and one of the first Eastern European Jewish synagogues in the US. In 2009 she joined the Tenement Museum, where she served as director of education for nine years and worked to expand the mosaic of immigrant stories.

“Even as we were adding the Puerto Rican story and the Chinese story,” she says, “we realized that the diversity of students who were coming through wasn’t fully represented by the limited number of apartments we had.” To address this, Polland’s team created Your Story, Our Story, a website where people could tell their own stories by writing about a special object in their home or a cherished family tradition. The website now boasts more than sixteen thousand stories.

Polland left the Tenement Museum to lead the American Jewish Historical Society on West 16th Street, then returned as president in January 2021. Her first task, aside from reopening from the pandemic, was to add the story of a Black family, the Moores, who lived in a nearby tenement during the Civil War. Like the other apartments, the Moores’ re-created dwelling brings the visitor into new proximity with history and the ordinary people who made it.

“I cannot think of a better way to put my training to use — bringing scholarship to the public to help us collectively broaden our understanding of the past,” Polland says.

For Polland, the museum, which draws 225,000 visitors a year, also speaks to what it means to be a New Yorker today — and an American.

“We want to keep highlighting the stories of the real people who lived here, and through them try to understand the complex history of the nation,” Polland says. “I think this museum is a haven — a haven for an expansive American identity.”

This article appears in the Fall 2025 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "The Little Rooms Upstairs."