New views on ALS

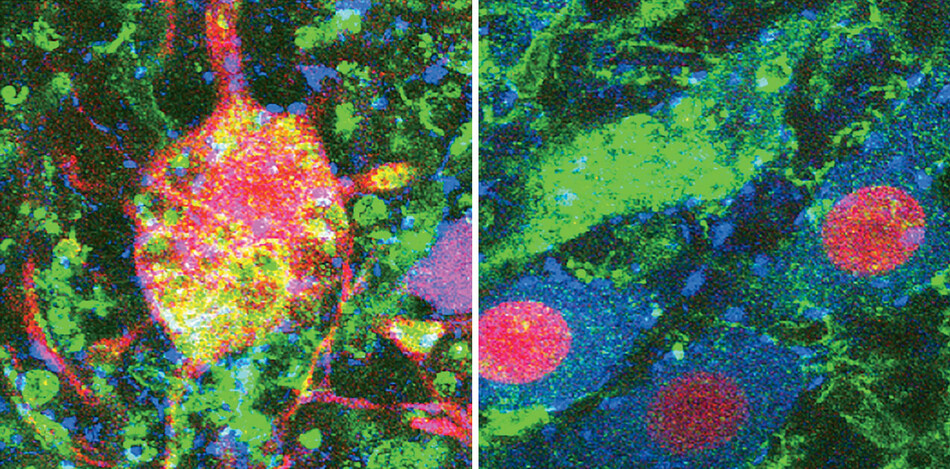

Two groups of Columbia researchers have achieved striking new insights into amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

One team, led by neuroscientist David Sulzer ’88GSAS, has uncovered the strongest evidence yet that ALS is an autoimmune disorder. Working with colleagues at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology, the Columbia scientists found that inflammatory cells mistakenly target proteins in neurons, and that the intensity of this attack determines how quickly the disease progresses. The researchers argue that ALS might one day be treated with medications that dial back the body’s immune response.

Meanwhile, a second Columbia group, led by pathologists Emily Lowry ’07BC and Hynek Wichterle, has shown that neurons can be restored to a more youthful state and thus made more resilient to ALS. In a study on mice, the scientists report that a gene therapy they’ve developed rejuvenated neurons and delayed the onset of symptoms.

Lowry and Wichterle, who are codirectors of Columbia’s Project ALS Therapeutics Core, point out that the disease often takes decades to emerge even in people with the strongest genetic predisposition to it, highlighting the potential benefit of slowing neuronal aging. They hope their research will also reveal strategies for treating other age-related neurodegenerative conditions, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

“Everyone is looking for the fountain of youth,” Lowry says.

Could AI detect concussions?

People who have suffered concussions exhibit subtle swaying head movements that are indiscernible to the human eye but detectable by artificial intelligence, according to a team of Columbia physicians led by Thomas Bottiglieri. The team is developing software to recognize these movements — which appear to be caused by temporary damage to the brain’s cerebellum — in order to identify athletes who are concussed but either unaware of their injury or reluctant to report it.

The hidden profits in cheap housing

Conventional wisdom holds that investors shy away from affordable-housing projects because they’re not sufficiently profitable. But a new study coauthored by Columbia Business School finance professor Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh finds that low-rent apartments actually deliver the strongest risk-adjusted returns in the US, in part because during economic downturns they remain fully occupied. The real reason many investors avoid them, the researchers conclude, is that they see reputational risk in owning cheap properties. They say that expanding access to capital for such projects, such as through low-interest loans to smaller landlords, could help to solve the country’s housing crisis.

How blocking the sun could backfire

A small but growing number of scientists have begun supporting the idea of spraying sunlight-reflecting particles into the earth’s atmosphere to combat global warming, but a new Columbia study warns that the proponents dramatically underestimate how risky this would be. The study, led by atmospheric chemist V. Faye McNeill, finds that so-called “stratospheric aerosol injection” could alter the jet stream and disrupt the patterns of air movement that circulate heat across the earth, in addition to damaging the ozone layer.

Pesticide linked to brain abnormalities

Prenatal exposure to the widely used pesticide chlorpyrifos appears to put children at risk for structural brain abnormalities and poor motor skills, according to a new study by Columbia public-health researcher Virginia Rauh. The study is the first to demonstrate enduring molecular, cellular, and metabolic effects of chlorpyrifos, which activists have been pushing the federal government to ban for decades.

An organ donor’s perfect run

Several teams of Columbia transplant surgeons recently carried out a rare “domino” procedure, in which one organ donation set off a chain of additional life-saving operations. First, an altruistic donor gave up half their liver, which was given to a patient whose own liver was not working well for them because of a metabolic disorder but was otherwise functional. Once removed, that person’s original liver was divided and transplanted into two other recipients. More than thirty clinicians, spread across four operating rooms, took part. Because the liver can regenerate, the donated portions are expected to regrow to full size.

This article appears in the Winter 2025-26 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Study Hall."