China’s hosting of the Olympics this coming August was an opportunity for Beijing to present the world with a new, more benign image of China as a modern superpower. Instead, in March, Tibet erupted and protests spread over an area of the Tibetan plateau that encompasses almost one-quarter of China. Troops were sent in, arrests made, reporters expelled, and imprisoned monks ordered to undergo patriotic reeducation. These actions didn’t help China’s attempts to appear tolerant and transparent. A few weeks later, the journey of the Olympic torch across the globe was disrupted by pro-Tibetan and human rights demonstrations. Politicians in the West threatened to boycott the opening of the Olympic ceremonies and urged the Chinese politburo to reopen talks with the Dalai Lama. Beijing has reluctantly agreed to do so, but some experts see the move as cosmetic. The leaders in Beijing continue to put the full blame for the Tibetan turmoil on the Dalai Lama, labeling him a separatist and a terrorist supported by hypocritical Western governments. The Dalai Lama, for his part, has accused China of oppressing the Tibetan people and producing a “cultural genocide” in Tibet. None of the underlying issues has been resolved, and instead, the argument has become a question of national pride.

We spoke to three leading Columbia University experts on Tibet, China, and Buddhism — Andrew James Nathan, Robert Barnett, and Robert Thurman — and asked them about the root causes of the conflict, the state of Tibetan culture, and the chances of a Chinese-Tibetan rapprochement.

Andrew James Nathan is professor and chair of the Department of Political Science

At Columbia you teach a course on Chinese foreign policy. You are also a human rights activist and cochair of the organization Human Rights in China. How do these different roles interact?

I very much believe in pressing the Chinese government on human rights. I also teach what I believe drives Chinese policy regarding these issues, which is fundamentally its national security interests: China sits on the mainland of Asia surrounded by 24 other countries.

My job on campus is to teach the Chinese perspective and policy to my students, which may lead to some pretty pessimistic conclusions about China’s tolerance of political and religious freedoms. Then I take the subway downtown to human rights organizations, where my job is to try to push the human rights situation forward. I’m pretty pessimistic downtown, too. China is a country of 1.3 billion people, all with their own perspectives on things. We’re trying to move them and push them, and it isn’t easy.

What is China’s view of its relationship with Tibet?

First, the Chinese government asserts, correctly, that it has internationally recognized sovereign control over Tibet, that Tibet is part of Chinese territory, and that Tibet belongs to China. In fact, there is not a government in the world that challenges Chinese sovereignty over Tibet.

Second, the Chinese view China as a multiethnic nation. It has 56 nationalities and the Tibetans are one of them. They recognize the cultural existence of a Tibetan minority, but that doesn’t alter the fact that Tibetans carry the passports of the People’s Republic of China and have Chinese citizenship.

The third point is that the Chinese actually acknowledge the so-called autonomy of Tibet by allowing the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), as well as the various Tibetan autonomous prefectures and provinces where Tibetan populations are in a majority. So the Chinese feel they have gone a long way to accommodate the cultural identity of the Tibetans.

Finally, China feels it has invested a lot of money in the economic modernization of Tibet to raise the living standards of the Tibetan people.

Did the March rebellion threaten the unity of China?

I wouldn’t call it a rebellion. There were mostly peaceful demonstrations and they were absolutely not an imminent threat to the unity of China. It’s impossible for the Tibetans to mount any kind of serious threat to Chinese control.

The Chinese feel that if they were to back off and grant additional freedoms, as some Western nations suggest, then Tibet would be a threat. If the Chinese were to accept the Dalai Lama’s 1988 proposal, which calls not only for the Tibetan Autonomous Region but also for the withdrawal of Chinese troops from the larger, historical Tibet, then that would be very threatening to Chinese security and create a power vacuum. So the Chinese feel they need to be in Tibet for their own protection.

Do you see any possibility for a compromise between China and the Dalai Lama?

As a practical political matter, I don’t see room for a compromise. In an ivory tower context you can envision compromises, but in reality there is no trust between the Dalai Lama and the leaders of China.

As far as the leaders in Beijing are concerned, there are several key factors preventing any loosening of controls. One is that the Tibetan population is spread over a vast territory, about one-quarter of the total territory of the People’s Republic of China, so a lot is at stake.

Second, the reverence that the Tibetan people hold for the Dalai Lama means that the essence of any proposed compromise would be for the Dalai Lama to return. But that would unleash an uncontrollable dynamic that the Chinese fear. So it would be very hard for them to say, “OK, we’ll meet you halfway and you can come back,” because that would be the beginning of the end of the story.

The third factor is that the Chinese don’t trust the Indians, the Americans, and the Europeans not to meddle and take advantage of any compromise that China might offer to increase their own influence in Tibet. In short, the Chinese feel that any concessions will make things worse, not better.

Has the Olympic spotlight put pressure on the Chinese to change their ways?

The Chinese respond very marginally and grudgingly to international pressure. In the lead-up to the Olympics we have seen the leadership increase its crackdown not only in Tibet, but in Beijing as well. They have tried and sentenced some human rights activists on the flimsiest and most transparently ridiculous grounds. If other people outside don ’t like it, that’s a cost that the Chinese are prepared to bear.

What about the April announcement that the Chinese are going to reopen talks with the Dalai Lama?

It’s a cosmetic move that offers no hope for real dialogue. It was announced before the Tibetan side was even consulted. I understand that the Chinese will be represented by a vice minister of the Communist Party United Front Work Department, a person authorized only to repeat the official line. The announcement of the dialogue was followed by repeats of the attacks on the Dalai Lama. Signs of seriousness would have been assigning a high-level person to hold secret talks with the Dalai Lama’s representatives, announcing nothing until something had been accomplished.

Will the Tibetan demonstrations end after the Olympics?

The Tibetan population has been dissatisfied for decades and that dissatisfaction is going to be there for decades into the future. But I think that this episode of street demonstrations will not be sustained. The Chinese will suppress it and things will resume as they were before, which was a simmering state of discontent, with arrests, imprisonments, and political persecutions going on more quietly.

Chinese nationalism, both in China and among Chinese abroad, appears to be on the rise.

I think nationalism is a permanent part of the Chinese landscape. The Chinese feel misunderstood. I’ve been really impressed with the Chinese in this country. My students who have gotten PhDs and gone into political science are completely conversant with human rights issues and understand the viewpoints of others. But at the end of the day they have not changed their fundamental view, which is, “Why should China not be as great a nation as the other major powers? Why does it have to be the one that compromises all the time? The U.S. is out there throwing its weight around to defend its own interests, why should China do no less? What do you want us to do with Tibet? Give it over to the Indians? Would that be better? Let the CIA run it, is that better?”

What are the most productive tactics in trying to change Chinese policies?

A mix of approaches is necessary. The leverage of the concept of human rights is fundamental. In Tibet, the Chinese are clearly violating the rights of predominantly peaceful, unarmed demonstrators who have a set of religious, political, and economic grievances. These are legitimate grievances and we have to press for the Tibetans’ internationally recognized right to express them to the Chinese government. Progress on that front is incredibly slow. But there are quite a few people and organizations vested in what is called constructive engagement that support a civil society in China. The UN special mechanisms to encourage human rights dialogue are also important. So it’s essential that the outside world keep the spotlight on China’s human rights violations. It’s not easy to see results in the short term, but one has to do that and hope that various constituencies in China will be impressed by the arguments that we are making.

Former journalist Robert Barnett is director of the Modern Tibetan Studies Program at Columbia

Is China implementing “cultural genocide” on Tibet?

The phrase cultural genocide is controversial because it has an association of deliberate intent to exterminate. That is not what the Dalai Lama was thinking (he later moderated his use of “cultural genocide” with the qualification “whether intentional or unintentional”). So I wouldn’t encourage us to think in terms of atrocity, evil, or racism. The Chinese Communist Party believes that it is trying to do good. The problem is, their efforts do not seem to be resulting in good or being perceived as good.

In your book Lhasa: Streets with Memories, you describe some of the cultural effects of the Chinese efforts to modernize Tibet.

One of the troubling results of the Chinese attempt to modernize Tibet has been cultural erosion. But it’s a complex question because all cultures are always being eroded, especially by modernization. At the same time, these cultures rarely disappear, unless their languages disappear. Tibet is a major world culture with a huge literary and religious tradition. It has vast resources. So we are not looking at a disappearance. And we don’t know whether the erosion we are seeing is the side effect of modernization or the result of deliberate Chinese state policy.

What are some examples of this cultural erosion?

The Chinese state has failed to live up to its promises to provide education in the Tibetan language beyond primary school, while the Chinese language is strongly promoted as the language you have to learn in most work fields. Tibetans also say that the Chinese have allowed prostitution and alcoholism to expand exponentially. That does appear to be true. There are many unemployed Tibetans in the city who have been lured from the countryside but have not been able to find work in urban areas.

What about the repression of religion in Tibet?

This is a big gray zone. Religion is banned only for certain sectors of the population. Government employees and students, if they are Tibetan or Buddhist, are not allowed to practice their religion. If the employees and students are Chinese or Christians, I don’t think those in power would mind. Again, this is not written down; it’s a practice that only applies to some people.

But the modern Chinese state deliberately and consistently denigrates religion, especially among what they call religious professionals. People take it for granted that monks and nuns are treated as pariahs by the Chinese state.

It comes out of a whole set of ideas about modernization. Religion is anathema to the modern.

Have the completion of the new China-Tibet railway and the arrival in Lhasa of thousands of Han Chinese migrants aggravated the situation?

As the Dalai Lama said, the train itself is neither good nor bad. What is important is whether the government is going to maximize the benefit of the train and minimize the damage. The damage has been done. Tibet has a very fragile ecosystem which is already overburdened in terms of population, and the train adds to the non-Tibetan population.

The Chinese government had the option to introduce mechanisms to regulate the flow of Chinese migration to Tibet, which understandably has been a huge concern to the Tibetans because that does have real impact on the culture. But the Chinese didn’t introduce those regulations. Perhaps much more importantly, they didn’t allow the Tibetans to discuss this issue. They made the argument, using free market reasoning, that the state can’t regulate internal migration. And once you play that demographic card, you really start to unleash cultural factors.

What will the Chinese do?

I’m sure they will take steps to try and find out what went wrong and make changes. Behind closed doors, China will search for economic solutions; it has no other choice after the events of this spring. Once they have Tibet under military control, they will send teams in to try to solve the economic problems and make sure the Tibetan workers have more money. That farm workers have jobs. But not many people think that these kinds of economic solutions can solve political problems, which have to do with history and memory and religion and culture.

What will happen after the Olympics?

One has to worry that all of this has been compressed into such a small time frame and will exhaust the international communities’ interest in Tibet and after the games they will lose their focus. It’s hard; we are looking at windows of opportunity that come and go with increasing speed.

A student of the Dalai Lama, Robert Thurman is the Jey Tsong Khapa Professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies in the Department of Religion

What brought on this crisis?

The Chinese repression of the Tibetans. For the past two years Chinese officials like Zhang Qingli (the Communist Party secretary for Tibet) and Premier Wen Jiabao have reverted to Cultural Revolution rhetoric, demonizing the Dalai Lama, denigrating Tibetan Buddhism, and shoving an illegitimate Panchen Lama (the second-highest-ranking religious figure in Tibetan Buddhism after the Dalai Lama) down the Tibetans’ throats.

They have also done a lousy job with the Tibetan economy, which may be viable for the Chinese migrants but not for the Tibetans. Nor have they kept the promises they made when the new railway was built from Qinghai to Lhasa, which has resulted in the settlement of increasing numbers of Han Chinese in Lhasa. So this religious and economic humiliation pissed off the Tibetans and sparked the uprising.

Has the Dalai Lama changed his method of dealing with China?

The Dalai Lama’s Middle Way foundered last year with the collapse of the dialogues with the Chinese government, which were just a Chinese delay tactic anyway. For several years the Dalai Lama was surrounded by a Chinese appeasement group. (They said, “Let’s be very nice. Let’s have nice atmospherics.”) But the Chinese were just getting harder and more repressive. They bottled up Tibet for four or five years and that created a lot of frustration. The Dalai Lama was really discouraged by this. But this year he has been more vigorous and outspoken. In his March 10 statement, he said that the dialogue had not accomplished anything, and it was time for a change. The Chinese appeasement group had to eat crow.

But isn’t the Middle Way in crisis? On the one hand, the Dalai Lama’s pacifist diplomatic approach has led nowhere. On the other hand, there have been violent protests and the Tibetan youth are getting tired of waiting for results. Isn’t the Dalai Lama in a bind?

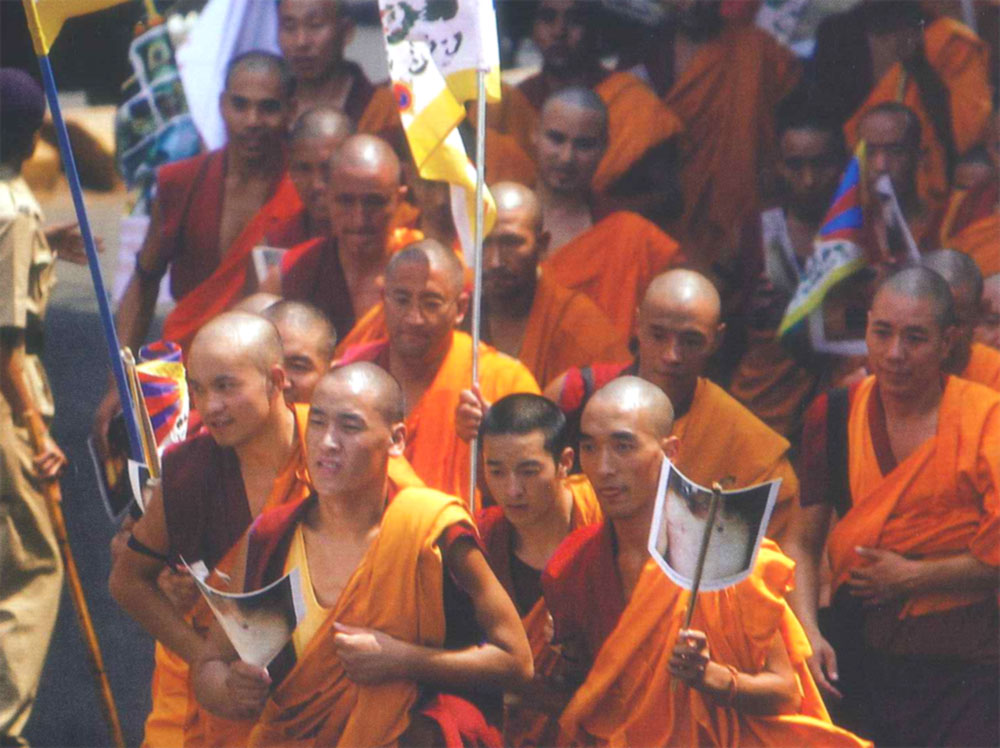

There are some hotheads in the Tibetan movement who say, “We have to take up arms!” But these people are in a minority. His Holiness disapproves of the violence, but he is extremely heartened by the outburst of feeling all across Tibet. Not just in Lhasa, or the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), but all across the eastern regions that are sympathetic to Tibetans. Because this shows that when the Chinese say it is just a small Dalai Lama clique that is bad and creating all the problems, they are wrong. The widespread protests demonstrate that the Dalai Lama’s clique is, in fact, all Tibetans. So if the Chinese say, “We’re going to neutralize Tibetan culture,” that means stamping out the Tibetan-ness of all the Tibetans.

Will the Dalai Lama follow through on his threat to resign?

He could if the violence continues. The Dalai Lama is very upset by the violence. He has an agreement with India not to use violent tactics. He cannot continue to live like a monk and condone it. He has also said vis-à-vis a Tibetan man who burned himself to death in Delhi 10 years ago, that he is against such self-martyrdom (the Chinese have accused the Dalai Lama of preparing suicide bombers). But at the same time, these monks in Tibet are being made to read Mao’s Little Red Book, their compatriots are being taken away, put in jail, killed, and they freak out. It’s understandable, emotionally.

How are the upcoming Olympics influencing the situation?

The Olympics are a great opportunity for China to turn around. Either China will try to vilify and kill off the Tibetans or it will replace the leadership in Tibet. If the Chinese were smart, they would demobilize the two commissars in Tibet. They would change their policy and make a really bold change like Nixon did going to China, like Gorbachev did in the Soviet Union. The lesson is, you don’t crush your colony. It doesn’t work. President Hu Jintao and the Chinese politburo should invite the Dalai Lama to talks about restoring real autonomy to Tibet. World opinion about China would change. The whole Chinese politburo might win the Nobel Peace Prize!