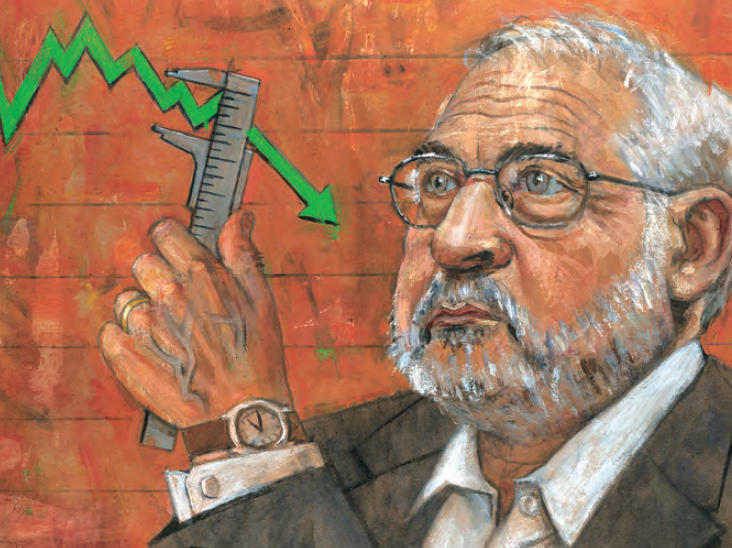

At 6:16 p.m., the door to the Presidential Room of Faculty House clicked open, and necks craned toward the entrance. Joseph Stiglitz, Columbia’s bearded, bespectacled, and perennially late Nobel Prize–winning economist, grinned at the standing-room-only crowd that had gathered for a discussion, sponsored by the Committee on Global Thought, about the role of governments and central banks in creating a new financial structure. Stiglitz made his way to an empty seat at the front table beside two similarly bearded panelists, economists Adam Posen and Benjamin J. Cohen ’59CC, ’63GSAS, who had been awaiting his arrival since 6:00 p.m.

Without ceremony, Stiglitz launched into an assault on Wall Street banks and their Washington allies, the villains in his decades-long campaign against what he and other critics call market fundamentalism. “It’s a lack of regulation, not low interest rates, that was the source of the financial markets debacle,” he told the audience. “Banks happen to have 51 percent of the votes in Congress.”

Maybe he’s tardy to speaking engagements, but when it comes to ideas, such as increased market regulation, Stiglitz, a University Professor of economics, often seems ahead of the curve: demonized and marginalized at first, and later — sometimes many years later — embraced.

Take his thoughts on gross domestic product. As a senior economic adviser to President Clinton in the mid-1990s, Stiglitz locked horns with the coal industry over a “green GDP” campaign that he supported. He and others in government had pushed to incorporate the cost of environmental damage and depletion when calculating gross domestic product, the predominant measure of an economy’s performance. That would have made the social costs of energy production more apparent to policy makers — a troubling prospect for producers. Big Coal lobbied hard, and the plan was killed. The idea wasn’t.

In 2000, Stiglitz ruffled more feathers. As chief economist of the World Bank, he launched a remarkable attack on the World Bank’s sister institution, the International Monetary Fund, accusing it of pushing Washington’s economic agenda — privatization and the lifting of price subsidies — on the developing world. The argument won him admirers in policy circles of Asia, but caused an uproar at the Bank’s Washington headquarters that led to his abrupt resignation.

Stiglitz continued his endorsement of government involvement in markets, and continued making enemies in the United States. Though he won the 2001 Nobel Prize in economics for research into the inefficiencies that arise when two parties to a transaction (say, a bad driver and his unsuspecting insurance company) don’t share the same information, in his own country he remained a pariah among policy makers.

But Stiglitz embraced his opposition status. He wrote books attacking the dogma of market liberalization in developing countries, and traveled abroad to advise foreign governments.

Then, in January 2008, while attending the annual meeting of the American Economic Association in New Orleans, Stiglitz received a call from France. The man on the other end was Jean-Paul Fitoussi, a prominent French economist. Fitoussi had a message from his president, Nicolas Sarkozy. “Sarkozy would like you to lead an official commission on the measurement of economic progress,” Fitoussi said.

Sarkozy hoped his commission would encourage governments to measure the well-being of citizens, not just raw output. And he knew that that would challenge decades of economic orthodoxy. Which meant he needed a fighter. “If I give this kind of report to be done by the mainstream,” Sarkozy told Fitoussi, “we will never come out with something different.”

Stiglitz was in many ways the ideal choice, a respected academic who can rouse a crowd with crisp provocations and wonky economic concepts. One of his favorites: “If you measure things wrong, you’ll do the wrong things.”

By its nature, says Stiglitz, GDP treats spending on prisons as it would on more productive services like education, and distorts the economy’s picture when economic bubbles, like in housing or finance, inflate to dangerous levels. GDP also ignores the depletion of resources, environmental degradation, and health impacts of mining in developing countries. “The result of that is the well-being of the citizens of the country can go down at the same time that the GDP goes up,” he says.

In the United States, Stiglitz points out, GDP has begun to rise even as the unemployment rate hangs above 10 percent, painting a misleading picture for policy makers. “When the numbers that a government announces seem incongruous with what happens in people’s lives,” he says, “the public thinks the numbers are being manipulated.”

The commission’s work, touching on new ways to measure quality of life, economic sustainability, and technical adjustments to the current GDP metric, became the centerpiece of an October conference of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the so-called rich-nations club, which has taken up an investigation of its policy conclusions. It has also prompted the influential G-20 to call for improvements in the way official statistics measure the well-being of citizens.

“The job of an economist is not just to describe the world,” Stiglitz has said, “but to work to improve it.”

Has history finally come around to Stiglitz’s activist vision?

Time will tell, but with the backing of a head of state and increasing support in America for government intervention in markets, Stiglitz is anxious to seize the moment. “You can push on an issue, and if it’s not an opportune time, it won’t have an impact,” he says.