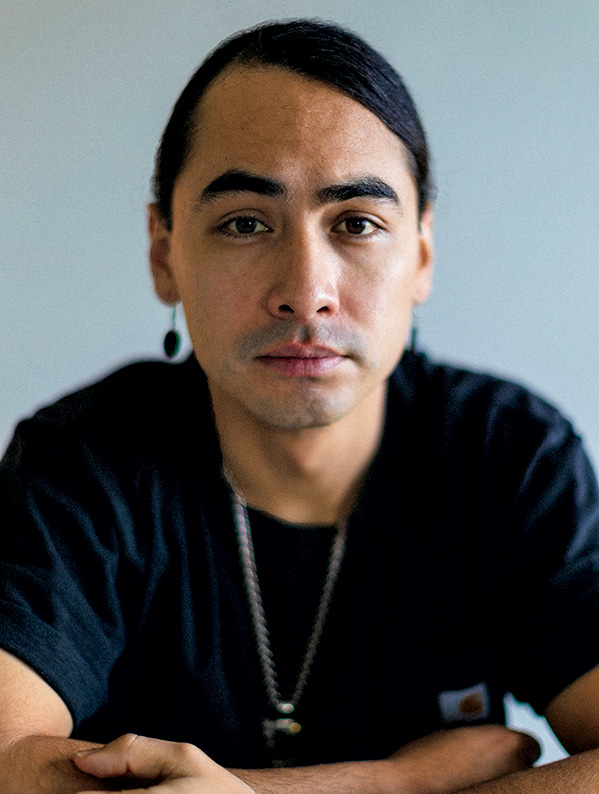

In Secwepemctsín, the northern Interior Salish language spoken by the Secwepemc or Shuswap First Nations peoples, who live in British Columbia, a typical morning greeting is Tsecwíncuw-k: you survived the night. Julian Brave NoiseCat ’15CC learned this phrase from his kyé7e, or grandmother — one of the last remaining fluent native speakers of their tribal language — while studying with her on the Canim Lake Reservation during his first two summers off from Columbia.

“I often wonder what it meant for our people to greet one another and the day with the simple but profound acknowledgment that we are still here,” NoiseCat, a member of the Canim Lake Band of the Secwepemc and descendant of the Lílwat Nation of Mount Currie band of the St’at’imc, writes in his first book, We Survived the Night. That survival, despite centuries of attempted erasure by the settlers of North America, has been hard-won. Its personal, historical, and contemporary dimensions form the foundation of NoiseCat’s inquiry, which he approaches by weaving together lexéy’em (oral histories), tspetékwil (legends), memoir, and on-the-ground reporting to create a work as intricate as the baskets his great-grandmother once crafted. The result is a multifaceted restoration of Native history and a celebration of contemporary Native life that rejects romanticization in favor of more honest, complex truths.

We Survived the Night opens with a moment of Native survival significant to NoiseCat’s own life. In August 1959, a night watchman at the Catholic-run Indian boarding school at St. Joseph’s Mission in British Columbia heard a cry coming from the garbage incinerator. Amid the soot and trash, he found a newborn boy: NoiseCat’s father. He had escaped not only imminent death but a systemic, continent-wide scheme to kill Indigenous peoples’ cultures.

Kyé7e and her siblings had been sent to St. Joseph’s in the 1940s when an Indian agent and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police came to collect the children from Canim Lake. When Kyé7e later got pregnant out of wedlock, she knew that “illegitimate” babies born at the mission were routinely disappeared to the incinerator.

NoiseCat’s family had long avoided talking about their painful pasts at Indian boarding schools, including his father’s birth and improbable survival. But in 2021, when news broke that ground-penetrating radar had found what appeared to be 215 unmarked graves at the site of the Kamloops Indian Residential School — where Kyé7e finished high school — he felt that “the spirits of our missing children … were coming home. And their truths could not be hidden, suppressed, or ignored any longer.”

NoiseCat first exposed these truths in his 2024 Oscar-nominated documentary Sugarcane, for which he won the directing award at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival along with codirector Emily Kassie. Sugarcane follows NoiseCat and his father, Ed Archie NoiseCat — a renowned traditional carver whose work is featured in the Smithsonian — as they confront the grievous abuses perpetrated against Indigenous children for more than a century at St. Joseph’s, which closed in 1981.

In We Survived the Night, NoiseCat widens his lens far beyond the history of how Indigenous peoples have persevered despite the horrors they endured at residential schools in Canada and the United States, where stealing Native children was a means to expropriate land. He structures the book around a cycle of “Coyote Stories,” drawing on the often-told supernatural stories of his people’s forefather, an immortal trickster sent by the Creator with immense powers of transformation — precisely the powers that have enabled their survival. “Colonizers tried to remake us in their image or kill us — physically, legally, and culturally — countless times by countless means,” NoiseCat writes. “To survive, we remade ourselves and the world around us in whatever way we could — often and especially by getting into trouble like Coyote.”

NoiseCat doesn’t shy away from that trouble, because Coyote stories also “get at hard and often unflattering realities.” He meditates on “the choice our ancestors had to make in the face of colonization: resist or cooperate,” a conundrum still very much alive in the Indigenous world today. He grapples with the damage wrought by his father’s preferred coping mechanisms — abandonment, alcohol, and womanizing — and how those same tendencies live within him, too.

NoiseCat faces these unflattering realities because, as he writes, “That’s what it means to know someone. And that’s what it means to love them — all of them — too.” We Survived the Night is a love letter to the First Nations, which were long deprived of love by the people who sought to erase them, and to “the legends indigenous to this place,” which NoiseCat has preserved for readers to learn from.