Paul Auster was eight years old when an encounter with Willie Mays ended in disappointment so profound it changed his life.

In his essay “Why Write?” Auster explains that he had asked the legendary outfielder for an autograph but was unable to procure something to write with. “‘Sorry, kid,’ Mays said. ‘Ain’t got no pencil, can’t give no autograph.’”

Then Mays walked out of the ballpark into the night.

On an April evening more than five decades later, Auster read from this essay and then volunteered a postscript to a small audience in the basement of the Kraft Center for Jewish Life on West 115th Street.

A couple of years ago, Auster said, a neighbor of Willie Mays read Auster’s essay to the aging Hall of Famer. Mays listened attentively to how young Paul cried all the way home that night, despondent over his failure, ashamed that he could not stop the tears, but resolved to always carry a pencil in his pocket should anything as worthy as a Willie Mays signature need to be written down.

“If there’s a pencil in your pocket, there’s a good chance that one day you’ll feel tempted to start using it,” Auster wrote.

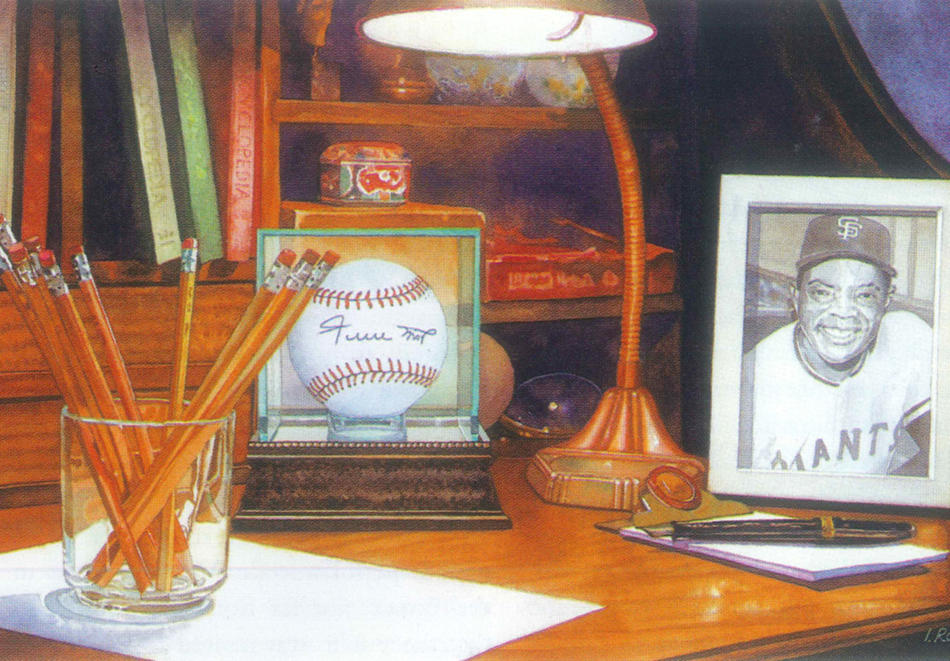

Upon hearing the unlikely story of how Auster became a writer, Mays grabbed a baseball, signed it, and had it delivered to the Brooklyn-based novelist.

“So now I have Willie Mays’s autograph,” Auster told the audience, “proving that books, or writing, can actually change reality.”

Auster had come to Columbia to take part in a series of conversations with authors sponsored by the Institute for Religion, Culture, and Public Life. Other writers have included Jonathan Safran Foer, David Ignatius, Philip Gourevitch, Dalia Sofer, and Uzodinma Iweala.

Mark C. Taylor, the institute’s codirector and chair of the religion department, moderated the talk, though he never really touched on the stated theme of literature and terror. Taylor later said he was hoping to move the meaning of the word “terror” beyond its current use as a synonym for terrorism.

Instead, Taylor asked Auster about the relationship between baseball and writing (Auster: “Sorry, there is none”) and whether solitude is the same as loneliness (“Solitude is voluntary”). Later, Auster decried the writer’s solitude, saying, “It’s a terrible way to live your life and only people who are really crazy enough, and I think even ill — I think it’s a disease — would want to shut themselves in a room and all their lives put words on pieces of paper. There’s so much else to do.”

Over the course of 90 minutes, Auster traced his evolution as a writer, his thoughts on language, on writing as a physical act (“I have this eerie feeling, especially with the fountain pen, that the words are coming out of my body”); and the role chance plays in life and literature. He sat cross-legged in black jeans, and when he wasn’t reading from his works, his black-framed reading glasses straddled his knee.

Auster is unlikely to ever carry a BlackBerry or iPhone. He does not use e-mail and doesn’t even own a computer, though you can fax him. He has written about his typewriter — and the painter Sam Messer has produced scores of portraits of that 1962 Olympia — but he writes longhand and transcribes later.

“It’s not a fetish, it’s just a comfort,” he said. Then, making claws of his hands and hovering them over an imaginary keyboard, he added, “I can’t even think with my hands in this position.”

Auster, who grew up across the Hudson River in South Orange, New Jersey, was 16 when he realized writing was all he wanted to do. By then, he said, he had written scores of terrible poems and a short detective novel that he illustrated in green ink and read in installments to his sixth-grade class.

At 14, having become a bar mitzvah as a matter of course, he began wrestling with what he called “all the big metaphysical questions.” In search of answers, he started meeting weekly with a rabbi. Six months later, he realized he had no interest in being a practicing Jew. Still, he finds inspiration in the Jewish tradition and its notion of justice.

“The Jewish idea of justice is there can’t be justice for only one people or one group,” Auster said. “There has to be justice for everybody or there is no such thing as justice.”

One of Auster’s main themes is chance, but that does not mean he believes that all events are random. Instead, he’s interested in crossroads, places where random occurrences (approaching the Say Hey Kid without a pencil, for instance) foil people’s well-laid plans, forcing them to figure out how to keep going. Faced with a choice, they must “reinvent themselves or fall to pieces,” he said.

When the talk ended, Auster was quickly approached by audience members carrying copies of his poetry, novels, nonfiction, and screenplays. The writer pulled a black pen from his pocket and signed every one.