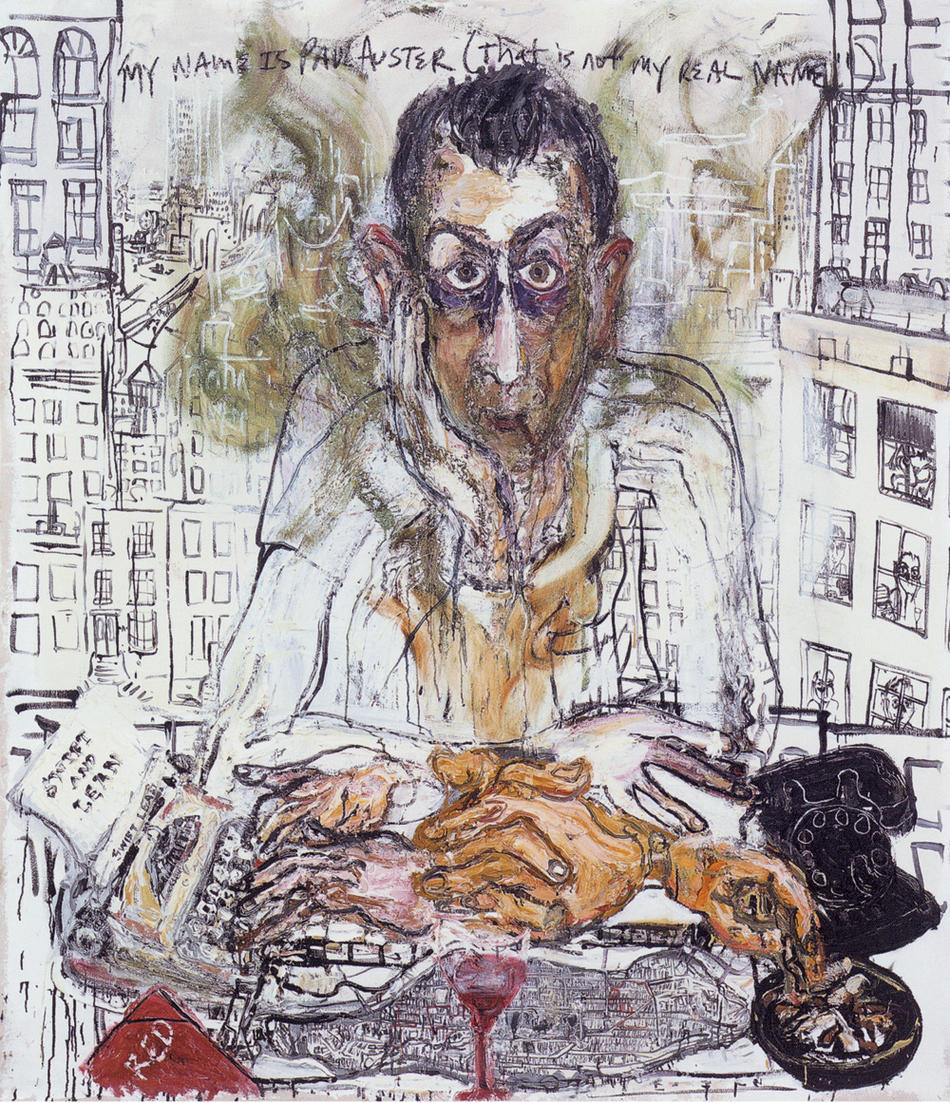

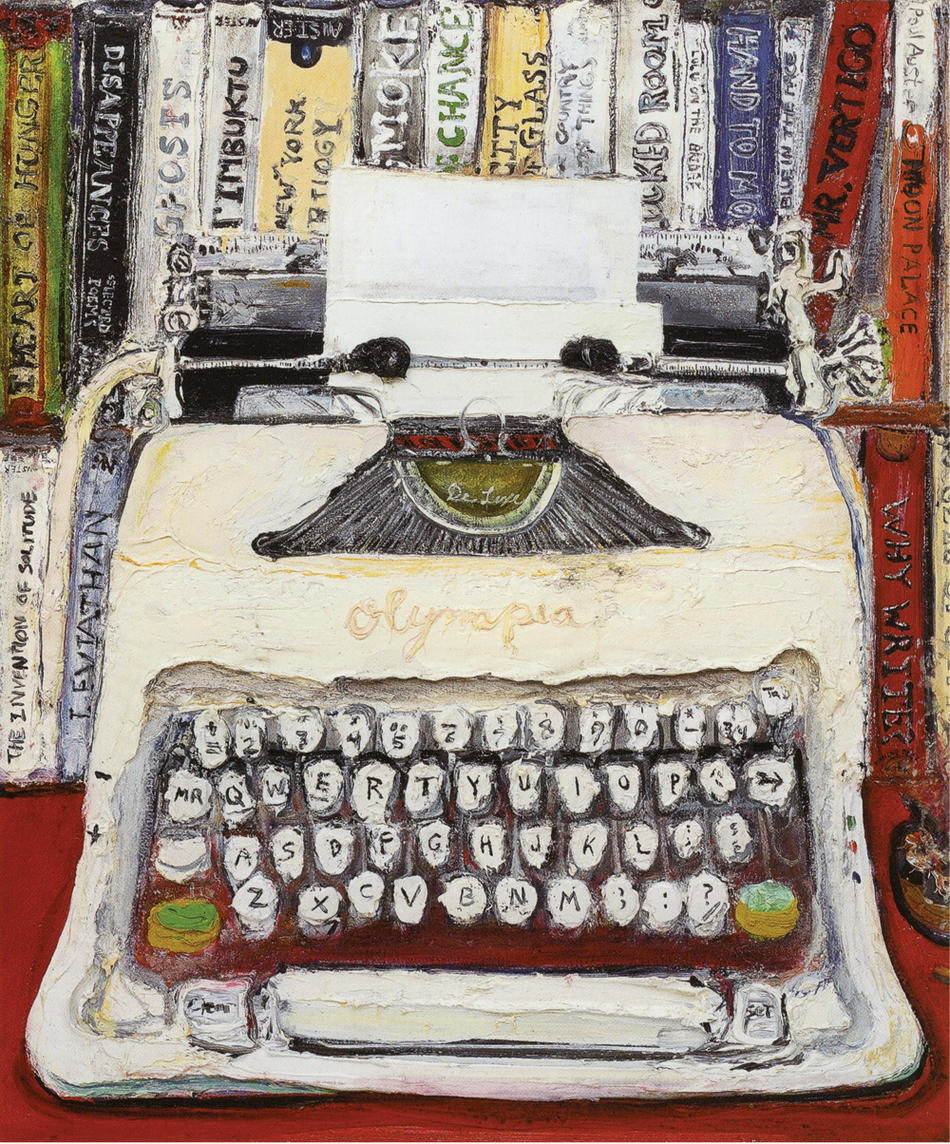

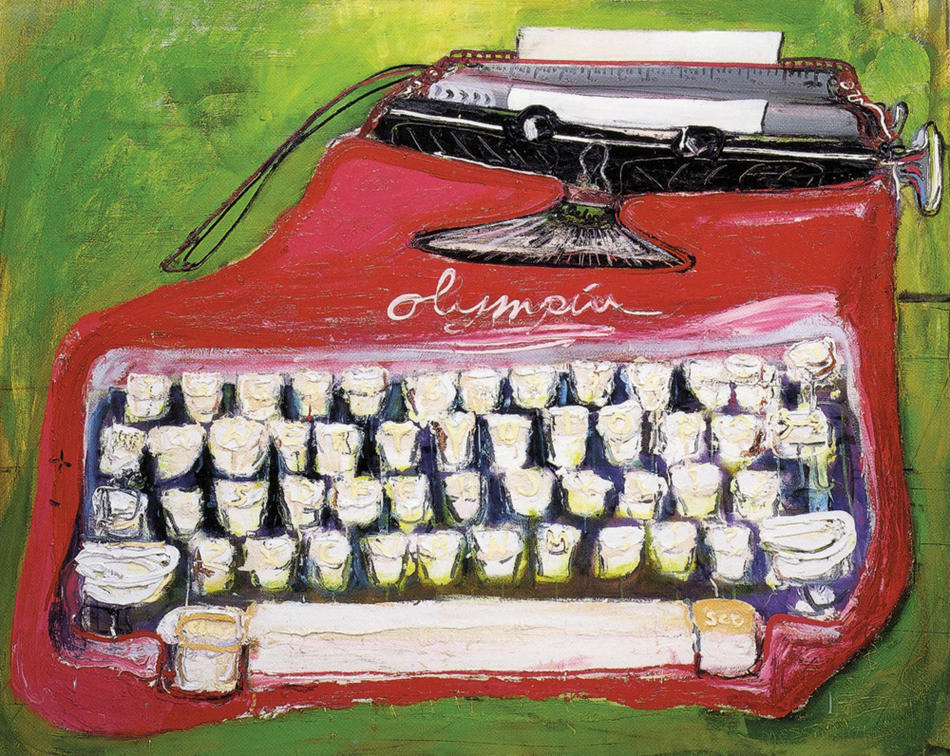

Paintings by Sam Messer, who has been painting and drawing Paul Auster, and Auster's Olympia typewriter, for many years.

“It happened right there, in that chair.” Paul Auster points to one of the upholstered Parsons chairs surrounding the Bordeaux-colored dining table in his Brooklyn brownstone. Staring blankly, he adds, “I wouldn’t wish that on anyone.”

The chair is where Auster ’69CC, ’70GSAS suffered his first panic attack, soon after his mother died suddenly in 2002. “I didn’t see my father’s corpse, but I saw my mother’s corpse. It’s a horrible thing to see your parent dead, especially your mother, because your body began inside her body. You started in that person. It’s a very, very traumatic business.”

The death of his mother is one of the experiences that Auster recounts in his latest work, Winter Journal, a memoir of the sixty-five-year-old writer’s life, from childhood to the present day. Winter Journal also explores what it means to be human and to live inside our bodies, with their curious collection of yawns, coughs, and sneezes. What it’s like to feel the ache of physical desire and the relief of urination; to abandon yourself to sports as a boy, and to girls as an adolescent; to walk aimlessly through snowy city streets and run recklessly down the baseline of a spring-green ball field; to endure searing pain and express soaring joy; to know love and know loss; to grow up; to grow old. It’s the story of Paul Auster, but Paul Auster as everyman, which he emphasizes by writing in the second person.

“Writing in the first person would have been too exclusionary,” says Auster, who speaks in a velvety baritone with a slight nap, perhaps from the Dutch Schimmelpenninck cigarillos that he chain-smokes throughout the day. “I see that my experiences are so similar to everyone else’s, because we all have bodies, after all. Something always goes wrong with our bodies. Or right with our bodies. First person would have been pushing people away. Third would have been too distant. So second seemed just right, where I could address myself as an intimate stranger or an intimate other. But then the ‘you’ has this rebound effect on the reader, who gets sucked in, and is experiencing it in a different way than a first- or third-person text.”

Auster sits in a deco-style club chair on the parlor floor of his century-old Park Slope home, smoking as he talks. The brownstone is in pristine condition, the original, ornately carved woodwork and intricate inlaid wood floors balanced by a minimalist, Scandinavian-modern aesthetic, which he attributes to his wife, the writer Siri Hustvedt ’86GSAS. Along with a display of family photos are the artifacts of literary success, including two of the numerous paintings created by artist Sam Messer of Auster’s manual Olympia typewriter, which he continues to use in lieu of a computer, and a bronze sculpture on the side table beside his chair.

“That’s my Asturias Prize,” says Auster. “It’s the biggest literary prize I’ve won. It’s sort of like the Spanish version of the Nobel Prize. They give awards in the arts, sciences, and humanities — all these wonderful people getting things.” A little uncomfortable about having it so prominently displayed, he adds, “It’s one of the last things Miró did. I don’t know where to put it, so we have it here, because it’s Miró.”

Before the awards ceremony in 2006, which was attended by Spain’s queen and crown prince and broadcast live on Spanish-language TV stations around the world, Auster was looking over his acceptance speech in his hotel room when he put his glasses on the bed and sat on them.

“Can you imagine? One of the stems was broken off, so I had to give this speech in front of, I don’t know, a hundred million people, like this.” He closes one of the earpieces and puts the glasses on, balancing them on his nose. “Fortunately, the glasses didn’t fall off.

“My biggest moment,” he says with a laugh, “and I sat on my glasses.”

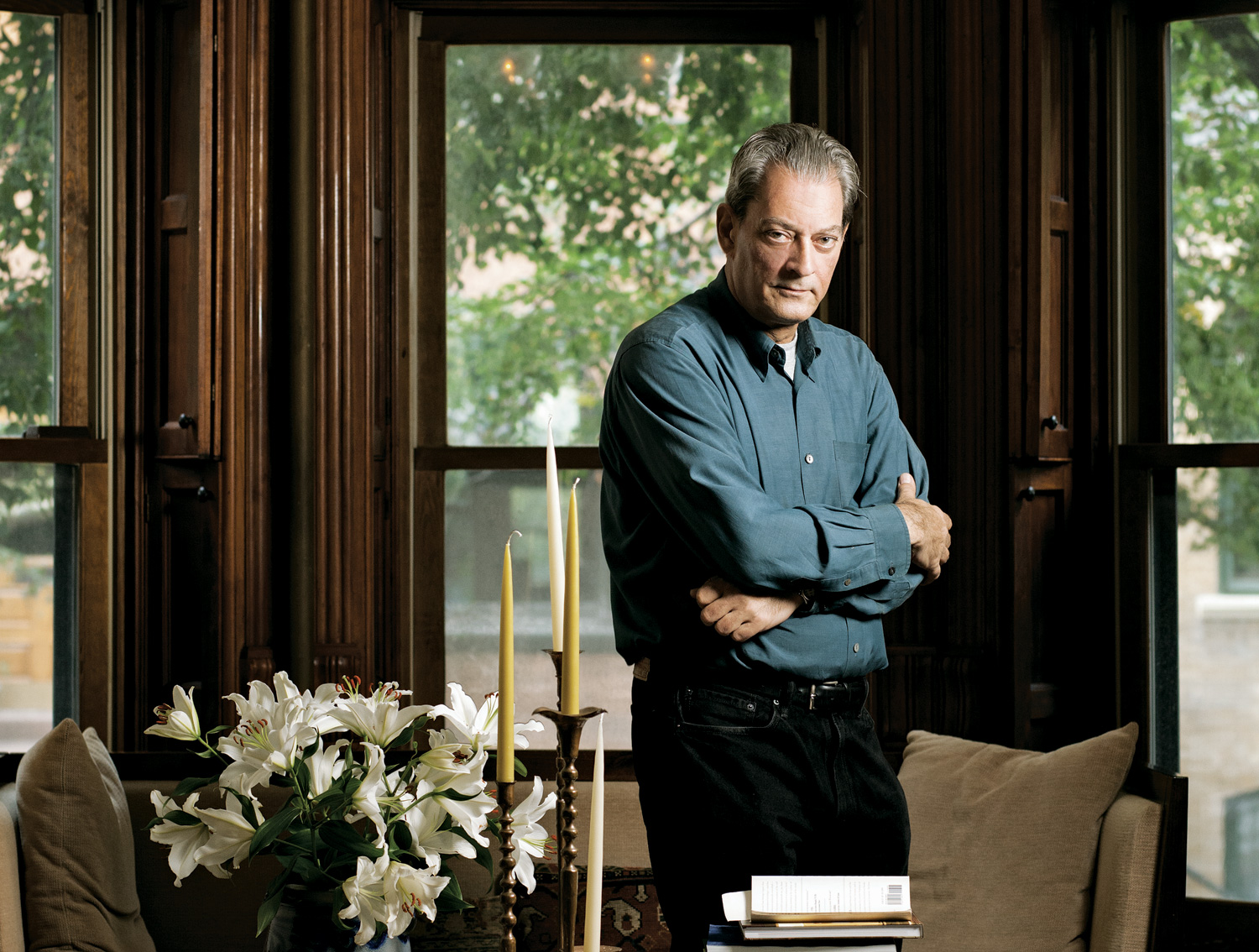

Given the scale of his success — his novels have been translated into forty-three languages — Auster’s sense of humor is surprisingly self-effacing. Readers familiar with his bleak tales of human suffering, loss, and failed attempts at redemption may marvel that he has one at all. (Even in his one attempt at a comic novel, Brooklyn Follies, a devastating hammer blow in the final paragraph obliterates the potentially happy ending.) His dust-jacket photos through the years seem only to confirm this image: Byronically handsome, with a strong, square jaw and penetrating gray-green eyes, Auster stares out soberly from his books, the embodiment of the brooding artist.

In person, however, Auster is warm and gracious, as keen to discuss baseball, his lifelong passion, as his writing. His darkly attractive looks have mellowed with time: his once thick, black hair thinning and silvery gray, the sharp cheekbones softened, the long, angular face fuller and rounder. Tall and broad, he shows a barely perceptible stoop to his shoulders that appears to be not so much a product of age as a slight shyness or self-consciousness in his physical person.

Taking a puff on his cigarillo, he glances again at the Asturias.

“It’s been a strange trajectory, I can tell you.”

It started in Newark and South Orange, where Auster had a middle-class suburban upbringing, liked by his peers and excelling at school and sports. His family life, however, was difficult: his parents were unhappily married until their divorce during his senior year of high school, his father an almost entirely absent figure from his life; his younger sister was diagnosed with schizophrenia in her teens. From a young age, Auster took to baseball as a physical outlet and writing as an emotional one, creating both fiction and poetry. He continued to pursue both genres rigorously while attending Columbia, first as an undergraduate and then as a master’s student in comparative literature. At twenty-three, he decided to drop fiction altogether and concentrate exclusively on poetry.

“At a certain moment I said to myself, ‘I’m not getting anywhere. I just can’t finish anything I start,’” he says. “I think it was probably a lack of confidence and a lack of a fixed aesthetic. But as I got older, I figured it out. Or at least I was able to do something with it. And finish.”

After Columbia, Auster spent a few months working on an Esso oil tanker to fund a temporary move to Paris, and lived in France for the next three years, where he wrote and translated poetry and worked for a movie producer, revising treatments and preparing script synopses. (While still in school, and on a junior-year-abroad program in Paris in 1967, Auster, a cinephile, had dreamed of breaking into the industry, even writing numerous script synopses for silent movies. But, he says, “I realized that my personality was wrong. I couldn’t talk in front of people. I was so shy. I thought, how can I direct movies if I can’t talk to people? So I more or less gave up the idea.” A quarter of a century later, Auster would write and co-direct his first movie, Smoke, starring Harvey Keitel and William Hurt, with three more to follow.)

In 1974, at the age of twenty-seven, Auster returned to New York with nine dollars to his name and two slim volumes of poetry to his credit. (“I had no idea how to earn my living.”) The next few years proved an intense struggle to gain financial footing. He married his college girlfriend, the writer and translator Lydia Davis; after she became pregnant with their son Daniel, they moved from their beloved New York City to a rural, ramshackle house in more affordable Dutchess County. Auster continued to write poetry, publishing a few more collections and chapbooks, but he spent most of his time trying to figure out how to make money. He shopped around a pseudonymous baseball murder mystery, Squeeze Play. He created a card game, which he illustrates in his 1997 memoir Hand to Mouth, that mimicked the play of a baseball game. Soon, the financial struggles evolved into marital ones, and he stopped writing poetry altogether.

“I didn’t abandon poetry,” says Auster. “It abandoned me. I just came to a wall.” Auster remains proud of his poetry, and for good reason: spare and deeply lyrical, it has a romantic intensity reminiscent of the twentieth-century Italian poet Eugenio Montale. Consider, for instance, Auster’s poem “Still Life”:

Snowfall. And in the nethermost

lode of whiteness,

a memory

that adds your steps

to the lost.

Endlessly,

I would have walked with you.

“It holds up,” he says. “But I haven’t written a poem since early 1979, half a lifetime ago. Except for family occasions — birthdays, weddings, anniversaries. I write silly rhyming poems for those.”

As Auster’s world was crumbling — bereft of money, marriage, and muse — he was invited by a friend to a modern-dance rehearsal. Watching the dancers interact, the powerful movement of their bodies, was a life-altering experience, a “scalding, epiphanic moment of clarity that pushed you through a crack in the universe and allowed you to start writing again,” as he recalls in Winter Journal.

“That dance performance unblocked me,” Auster says. “And then when I started writing again, it was prose. I found a new way to do it, a new approach altogether. I was liberated. It all became possible.”

The thirty-one-year-old Auster went home after the performance and immediately began to write, and continued to do so solidly for three weeks, working on a text that he describes as being “of no definable genre, neither a poem nor a prose narrative,” trying to explain all that he saw and felt during that dance performance. It was as he was finishing this piece, an eight-page work entitled White Spaces, that his father died of a heart attack while making love with his girlfriend.

“He died young, just one year older than I am now,” Auster says. “I wasn’t close to my father, who was an opaque person. He wasn’t unkind — I mean, he didn’t have any malicious thoughts toward me, just a kind of vague indifference, whereas my mother was very engaged with me from the beginning. Which is why I never really felt compelled to write about her with the urgency that I felt that I had to write about my father, who for me was literally vanishing.”

The resulting work was his first published book of prose. The Invention of Solitude is more than a biography of Auster’s father; it is also a haunting, meditative account of the darkest and most unsettled period in Auster’s life as he was experiencing it: the end of his marriage; the loss of his absent father; the separation from his own young son; the lack of money and a plan for the future; the gnawing emptiness. While not written expressly in narrative form, the second of the book’s two parts, entitled “The Book of Memory,” contains narrative elements; it is also written in the third person.

“I didn’t like it in the first person: something was wrong. I realized that I had to step back from myself, otherwise, I couldn’t do it. I was too close. By stepping back into the third, I think I was able to see things more clearly.”

The Invention of Solitude was the beginning of Auster’s move back toward storytelling. The ideas explored in “The Book of Memory” — loss and suffering, isolation and connection, chance and coincidence — would become the dominant themes in almost all of his subsequent work.

“I have always thought of that book,” he says, “as the foundation for everything that followed.”

When writing returned, Auster’s fortunes shifted. An unexpected inheritance from his father allowed him to avoid a desk job and continue on his path to becoming a novelist. Two years later, in 1981, he was introduced at a reading to a young writer and Columbia doctoral candidate, Siri Hustvedt. “I had this amazing experience of falling in love with somebody in about an hour,” he says, “and just jumping in blindly. Here we are, thirty-one years later, still together.

“To me,” he suddenly adds, “Siri is one of the greatest geniuses on the planet. She’s the smartest person I’ve ever known. Period.”

Auster’s first published fiction came in 1985: City of Glass, the first of three suspenseful, noir-style novellas with interconnected themes, that were later published together as The New York Trilogy. A postmodern, existential mystery, City of Glass is about a writer of second-rate detective novels, Daniel Quinn, who gets a series of calls looking for an actual detective. Bored and isolated, he decides to take on the detective’s persona, and soon finds himself implicated in a real mystery.

What makes City of Glass extraordinary is its exploration of identity through metafiction: Quinn writes his detective novels under a pseudonym, William Wilson; the frantic, repeated caller is looking for a detective named Paul Auster; and Quinn, after taking on Auster’s persona, meets the real Paul Auster, who is also a writer and not a detective.

“I’m fascinated by the artificiality of books,” Auster explains. “Everybody knows that when you pick up a novel, it’s something made up by somebody. Yet somehow we reify it. Somehow the protocol is that you’re not supposed to tamper with the rules. I was just curious to see what would happen if you take the name from the cover of the book and you put it inside the book.”

Auster is quick to point out that placing himself in the novel was not meant as a postmodern ploy, and had nothing to do with ego. “The Auster in the book is very similar to me in many ways,” he acknowledges, “the outward circumstances of his life more or less tallied with mine at the time. But I think of him as a rather foolish, even ridiculous, character. Everything he says is the opposite of what I think. I just was trying to make fun of myself.”

With the publication of City of Glass, Auster gained a cult of postmodern groupies; some fans retraced the protagonist’s travels around Manhattan, hoping to solve the mystery, and some years later, the book was turned into a popular graphic novel. When the other books in the trilogy, Ghosts and The Locked Room, were published, literary scholars also began to take notice. Auster was quickly establishing himself as a new and inventive voice in postmodern American literature.

Nearly thirty years and more than a dozen novels later, it’s hard to think of another contemporary American writer whose work generates more discussion and curiosity. “I must have over forty books about myself in the house,” says Auster, with more puzzlement than pride. “And I know that there are dissertations being written all the time. It’s rather extraordinary. There’s even a woman at the University of Copenhagen who’s setting up some Center for Paul Auster Studies. It’s all so strange that I can’t get my head around all of this.”

Academics theorize endlessly about Auster and his literary motivations, labeling him everything from a New York Jewish hunger artist to a clever semiotician whose every decision — down to the color of the notebook his protagonists choose to write in — is fraught with symbolism. Auster dismisses most of this as academic overanalyzing, usually with a hidden agenda.

“So many of these people have a point of view, a position, and are trying to articulate this position by using me as an example. But I myself, living within myself, never try to put labels on what I do. I just follow my nose.

“I’m a man of contradictions, you know; I can’t say any one thing about myself. Yes,” he says with a laugh, “I’m the hunger artist who likes to eat.”

Like every writer, Auster has his detractors; his, however, are unusually vicious. In 2009, with the publication of his novel Invisible, Auster received two particularly blistering, high-profile condemnations. In the New Yorker, James Wood began his lengthy critique with a parody of Auster’s writing that gave it as much stylistic credit as a dime-store thriller, and a bad one. Wood then mercilessly dissected what he viewed as Auster’s jumble of repetitive themes, implausible coincidences, hackneyed phrases, and lack of irony. The result, concluded Wood, is often “the worst of both worlds: fake realism and shallow skepticism.” In the New Statesman, critic Leo Robson bemoaned Auster’s predictability, going so far as to create a checklist of Austerian tropes: “Dead child? Check. A book-within-a-book? Check. Dying or widowed narrator? Double-check.”

In general, Auster doesn’t bother responding to his critics. “I know there are people who hate what I do and people who love what I do,” he says. But he wants readers to understand that his work is more straightforward than often perceived.

“I’m not trying to manipulate anything,” he says. “I’m just trying to represent the world as I’ve experienced it. That’s what my books are: a representation of what I feel about the world and how I’ve observed the mechanics of reality, which are very befuddling. The unforeseen is crashing in on us all the time. One minute you’re walking along the street, and the next minute a car hits you. I mean, my daughter, Sophie, was hit by a car a couple of months ago. She’s fine, but she could have just as easily been killed. These things happen every day in real life. So why shouldn’t novels have them?

“I think what critics forget is that I started as a poet,” he says, “and I still feel that I’m a poet. I don’t feel that I’m writing novels in the way other people are writing novels. I think of myself more as a poet-storyteller than a novelist.”

While not a justification for the shortcomings in his novels that have been pointed out by critics — no matter how unusual his approach, the end result remains a novel — it does help to explain the wildly divergent opinions about his fiction, the curious inconsistency of his language, and why millions of readers the world over have such a powerful, almost visceral, response to his work.

Through the years, the majority of complaints about Auster’s books have concerned the basic building blocks of a novel’s structure, such as plot and character development, and clichéd language, especially in dialogue. (Would a Swiss history professor, however sinister, ever say, “Your ass will be so cooked, you won’t be able to sit down again for the rest of your life”?) His protagonists rarely come with much backstory, their scant biographies largely lifted from Auster’s own life: they study at Columbia, travel to Paris, write poetry or fiction, obsess over baseball, and bear scars from dysfunctional families. He rarely offers more than a sketch of their physical appearance. And yet, we know their inner lives so well: their thoughts, their desires, their struggles, their solitude and suffering. We may not know where they came from, but we want to know where they’re headed.

Auster writes novels that have the emotional immediacy and resonance of a good poem. They are works of the moment, of present feeling and personal action. His language sometimes can feel forced and shopworn, even corny at times, when his characters are interacting with the outside world; but it is, like his poetry of old, spare and lyrical when he gets inside those characters’ heads and loses himself in the more impressionistic music of thought.

Take the opening of Man in the Dark (2008):

I am alone in the dark, turning the world around in my head as I struggle through another bout of insomnia, another white night in the great American wilderness.

Or these lines from Moon Palace (1989):

I had jumped off the edge, and then, at the very last moment, something reached out and caught me in midair. That something is what I define as love. It is the one thing that can stop a man from falling, power enough to negate the laws of gravity.

Over the three decades that Auster has been publishing fiction, his style and approach have evolved, moving away from labyrinthine plots to more straightforward storytelling. In his last few novels, there has also been a marked shift in his voice and an expansion of his methods. “I’ve opened up,” Auster says. “I’m using run-on sentences now, in ways that I never did before. I find it’s very propulsive, and especially good for capturing thinking, the internal monologue.”

Not only are the protagonists in these recent works more developed, but there are also more of them telling their stories: while several of Auster’s earlier novels split into double narration, Invisible, from 2009, has three separate narrators, and Sunset Park, his most recent novel, from 2010, has six.

“It was the story of all these people,” says Auster of Sunset Park, about a group of twenty-somethings squatting in an abandoned home during the financial and housing crisis of 2008. “We were living in an enormous cultural and societal crisis — the whole country was being booted out of their homes. So I knew I had to write a book with many voices in it. I think it’s also the only time I’ve written a book consciously about now, with a capital N, without any sort of time lag. The events of the book were only about two or three months old as I was writing it. It was very galvanizing.”

The rapid switching of storytellers in Sunset Park affords less room for filler; there remain some heavy-handed touches — one character takes photos of the personal possessions left behind in foreclosed homes he’s hired to clean, another runs a “hospital for broken things” — but it is one of the most fully realized of Auster’s novels.

“I’ve never written anything more quickly,” he says. “I wrote that book in such a condensed period — it only took me about four months, maybe five. I was absolutely burned out from the experience. I haven’t been able to write any fiction since.”

Instead, Auster is at work on another autobiographical book, which he won’t discuss until it’s nearer to completion. (“I don’t want to jinx it.”) After that, he’s hoping he’ll be ready to tackle fiction again. “I have ideas kicking around; I just haven’t felt ready.”

In Winter Journal, Auster muses on his profession:

No doubt you are a flawed and wounded person, a man who has carried a wound in him from the very beginning (why else would you have spent the whole of your adult life bleeding words onto a page?), and the benefits you derive from alcohol and tobacco serve as crutches to keep your crippled self upright and moving through the world.

“Most people wouldn’t want to be a writer, and for good reason,” Auster says, an early evening glass of white wine now accompanying the steady supply of cigarillos. “I mean, who wants to be shut up like that? People like to be with other people. To connect.”

The phone rings, and Auster jumps to answer it, apologetically, hoping it will be his wife. She left for London only that morning, but it’s clear that he already misses her. Instead it’s Auster’s agent, calling with an offer for a reading somewhere in Europe. (“Tell them I’m sorry, and that I wish I could, but there are so many requests.”) On the table, next to the Asturias Award, lies a literary publication with a cover photo of Siri, the woman Auster extols in his memoir.

“Oh, I had even more about her,” he admits, after returning from the call, “but I had to cut it back.”

The phone rings again a short time later, and Auster’s voice changes, taking on a softer, sweeter tone. “Hi, baby,” he says. “How’s it going?” It’s not Siri after all, but Auster’s twenty-five-year-old daughter Sophie, checking in. “Siri left this morning,” he tells her. “But I’m here all week, so stop by anytime.” Sophie, a singer, has a new album coming out, and just finished the photo shoot. Auster is eager to play her music for a guest.

He walks across the room to the media console and puts on an upbeat, South American–style tune, which he listens to with a small smile and obvious pride, wondering aloud if it is a tango. He follows it with a romantic ballad. Sophie’s sultry voice is full of heartache as she pines for her absent love. Auster sits silently, gazing straight ahead, his eyes glistening.

When the song ends, he sits still for a moment, then jumps from his chair and moves toward the stereo.

“Let’s hear one more.”