If you were ever tempted to give a book only fifty or eighty pages to make its case before you move on to another, here’s proof of why you mustn’t. You could miss one that’s as gloriously good as this.

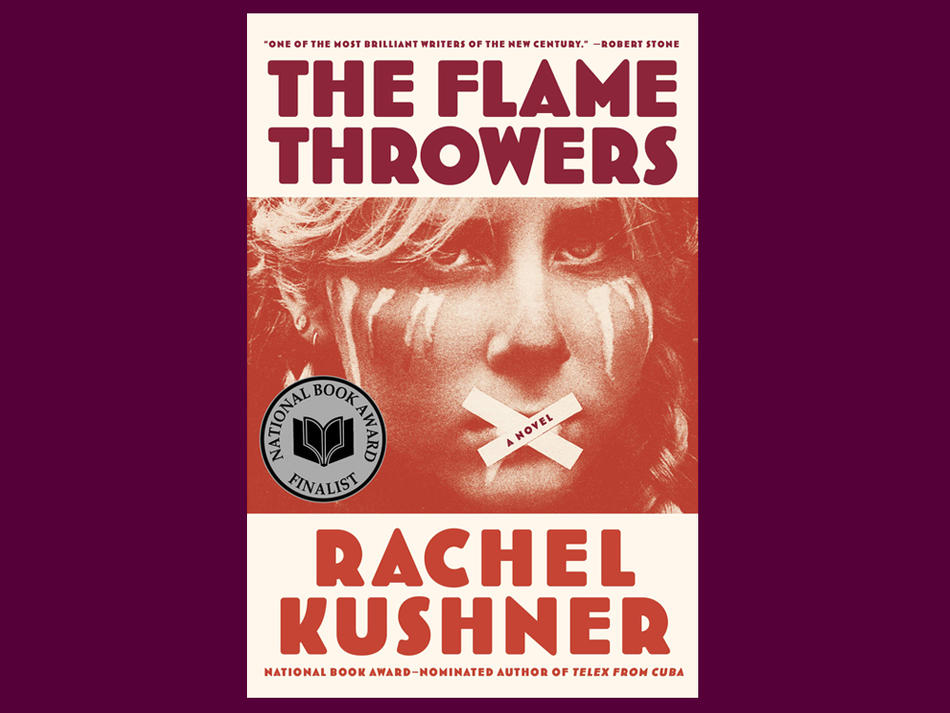

The Flamethrowers begins with a soldier in the Italian motorcycle squadron of World War I braining a German soldier, which initially seems unconnected to the rest of the book, set in the 1970s. Scores of pages later, we discover that the Italian soldier is the founder of a contemporary character’s family fortune. It’s a leap, but between here and there, if we’re patient, we find an astounding book. Not so much because of the plot, which traces the misadventures of a recent art-school grad from Reno who gets led by her heart into the treacheries of New York’s downtown art scene, and then into the treacheries of Italy’s old-money scene, and then into the lice-filled treacheries of Rome’s street-hardened Red Brigades scene. Good as it is, the plot is merely the delivery system for setting after setting so precisely informed and tone-perfect you won’t believe that Rachel Kushner ’01SOA (born in 1968) wasn’t there personally to taste and smell and see them.

Everything is more vivid than this morning’s breakfast. Back in our narrator’s grim Nevada childhood, her uncle Bobby, done hauling dirt for the day, “sat inexplicably nude watching TV and made us operate the dial for him, so he wouldn’t have to get up.” Once she escapes to Manhattan, driving her fancy Italian motorcycle across the country, she finds shelter in a walkup apartment above a Chinese family; because they slaughter chickens in their apartment, “the smell of warm blood filled the hallway.” (Notice Kushner doesn’t waste a second adjective on the blood; “warm” is evocative enough.)

It’s the era of Warhol’s Factory, and things get very dark very quickly. It takes no time for the narrator to crash into downtown hipsters who are all derelict in one sense or another, damaged but not fatally, and with such a shrewd take on life you can’t help but want to be beguiled by them yourself. Or at least listen to them soliloquize for hours. “It’s up here on the roof where all the good stuff is taking place,” a man says, “narrating the New York skyline” for her a few minutes after meeting her in a bar. “Women walking up the sides of buildings, scaling vertical facades with block and tackle. They dress like cat burglars, feminist cat burglars. Who knows? You might become one, even though you’re sweet and young. Because you’re sweet and young.”

This is how even minor characters chat in this cryptobohemian world. Impossibly feckless and fake, except when they’re not, they sometimes consider giving up the art scene to become chauffeurs for the Mob or to go to mortuary school — as a lark but also more than a lark. Everyone’s irony is so practiced, and so layered, that it’s pointless to object.

“Is any of it real?” our narrator asks about a certain monologist. “He’s complicated,” she is advised. “You have to listen closely. He’ll say something perfectly true and it’s meaningless. Then he makes something up, but it has value. He’s telling you something.”

Within this ardent miasma, Kushner’s descriptions are piercingly accurate and fresh. “I heard the sonic rip of a military jet, like a giant trowel being dragged through wet concrete.” “Only a killjoy would claim neon wasn’t beautiful. It jumped and danced, chasing its own afterimage.” The protagonist meets her principal lover on a “cold, damp November day on which the sun shone and rain fell simultaneously, the strange, rosy-gold light of this contradiction intensifying the colors around us as we walked.” Given all this, it’s perfect (and prophetic) that the lotus paste bun they sample on their first date “has more fragrance than flavor.”

The Flamethrowers is not without faults. The Red Brigades scenes are not quite as alluringly rendered as the others. Kushner can occasionally be facile: by way of underscoring the pope’s hypocrisy, she says he makes his plea for peace “with a giant bullet propped on his head.” She’s even sentimental at times: a gust of wind loosing pear blossoms from the trees is likened to “invisible hands [stripping] branches of their little white pearls.” But mostly she is brilliant in her specificity, nailing scene after scene in milieus both high and low, and creating a protagonist who is a woman on the verge, constantly becoming yet never quite there.