Girlchild, the debut novel of Tupelo Hassman ’06SOA, trots out all the unsavory characters you’d expect from a story that takes place in a trailer park: single-mom bartenders, absentee fathers, snobby girls from the right side of the tracks, sexual predators, and gambling grandmothers. Then there are those damaged by them, including the title character and narrator of the story, one Rory Dawn Hendrix. But in Hassman’s calm voice, these characters are rendered eerily complex, and the expected is turned on its head, making for a blisteringly beautiful narrative.

A young girl living with her mother “just north of Reno and just south of nowhere,” Rory Dawn understands the world in ways no schoolchild should. Her voice rings so clearly in our ears that it is a shock to learn, halfway through the book, that she hasn’t said a word aloud for months, a traumatic response to the sexual abuse she experiences at the hands of her babysitters. A mix between the bootstrapping Mary Call from Vera and Bill Cleaver’s young-adult novel Where the Lilies Bloom and the scrappy, intellectual child of Janisse Ray’s memoir Ecology of a Cracker Childhood, Rory Dawn is both the wisest and the most feeble-minded character in the book.

“I can hear all I want about sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll on the playground,” she says, so it makes sense that she is drawn to the Girl Scout Handbook, where she finds “step-by-steps for limbering up a new book without injuring the binding and the how-tos of packing a suitcase to be a more efficient traveler.” The reader intuits that Rory Dawn will likely never own a new book, but we keep reading in the hope that she may one day pack a suitcase — or even a brown paper bag — if it means she might be getting out of the trailer park.

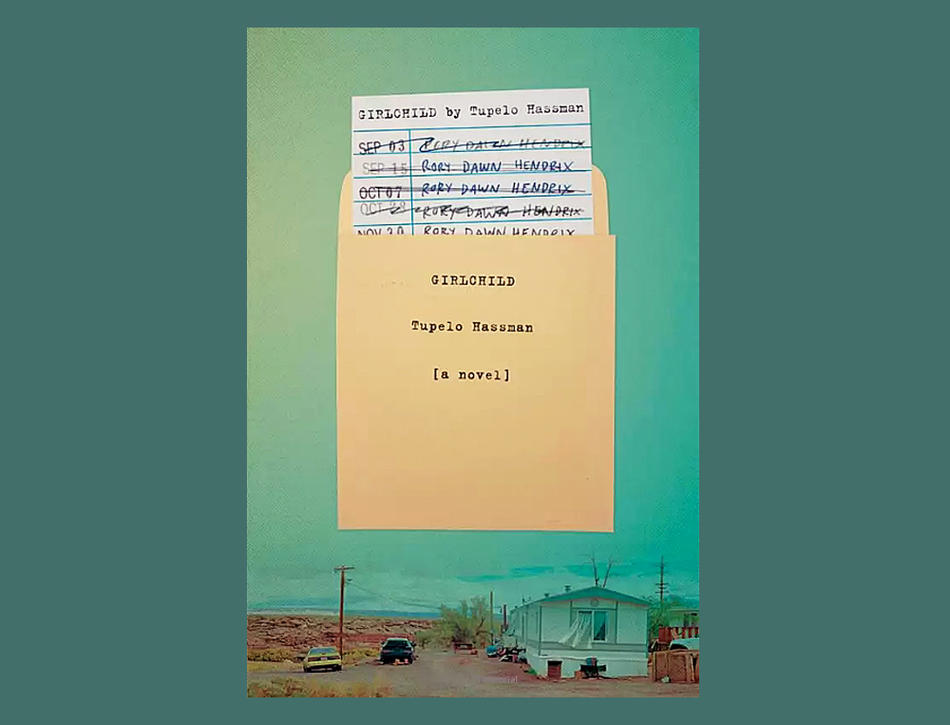

The first time we see the Girl Scout Handbook, Rory Dawn is using it as a prop as she spies on a cute neighbor boy. The book wasn’t always hers, she confesses: “At first, I borrowed it from the Roscoe Elementary School library, borrowed it over and over again until my name filled up both sides of the card and Mrs. Reddick put it in the ten-cent bin and made sure to let me know that she did.” This is not the last kindness Mrs. Reddick bestows on Rory Dawn; the librarian haunts the periphery of the book as one of the few adults in Rory Dawn’s world who neither abuses nor demoralizes her, even going so far as to chastise another teacher who offers her a backhanded gift of a pair of nude pantyhose before a spelling bee. Rory Dawn studies for the bee in the safety of the stacks, one of the only places she finds peace in her hardened world.

The level of detail Hassman layers into her pages is astounding. She shows us the rotten mouths of the neighbors in the trailer park, the “hands paused from stringing garlands of silver beer tabs,” and the grimy fingernails of the boys in shop class. She conveys the lifesaving quality of “a quick pour and a friendly smile” while evoking the deadening rhythm of the successive first and fifteenth days of each month. The narrator’s sexual abuse splays across the page, the specifics hidden under thick black redacting stripes — one of several narrative experiments. Prayers become prose poems, the consequences of a drunk-driving fatality get worked out on the page as a math problem, and facts leak out via clippings from caseworker files.

The short-burst chapters conjure the effect of shotgun fire riddling a street sign, a relentless rat-tat-tat whose tempo is impossible to escape. The form reflects the anxiety that runs through this book, like Rory Dawn furiously clawing at her own mouth to keep secrets from spilling out, or flattening herself on the ground after spotting some kids hopping a fence nearby. Hassman draws this terror viscerally, making us understand what it is to never, ever feel safe — not in your own town, not in your own school, not in your own home, not in your own body, and certainly not wearing your favorite rainbow T-shirt in the bathroom with the Hardware Man when the lights go out.

But in the end, though we spend most of the book waiting for someone to save her (or, if you are like me, waiting for Mrs. Reddick to invite her over for a sandwich and show her some college pamphlets), Rory Dawn is safest by herself.