Whatever may be the success of my stories,” wrote Mary Ann Evans to an editor in 1857, “I shall be resolute in preserving my incognito, having observed that a nom de plume secures all the advantages without the disagreeables of reputation.” Evans then signed the letter, and all subsequent work, “George Eliot.”

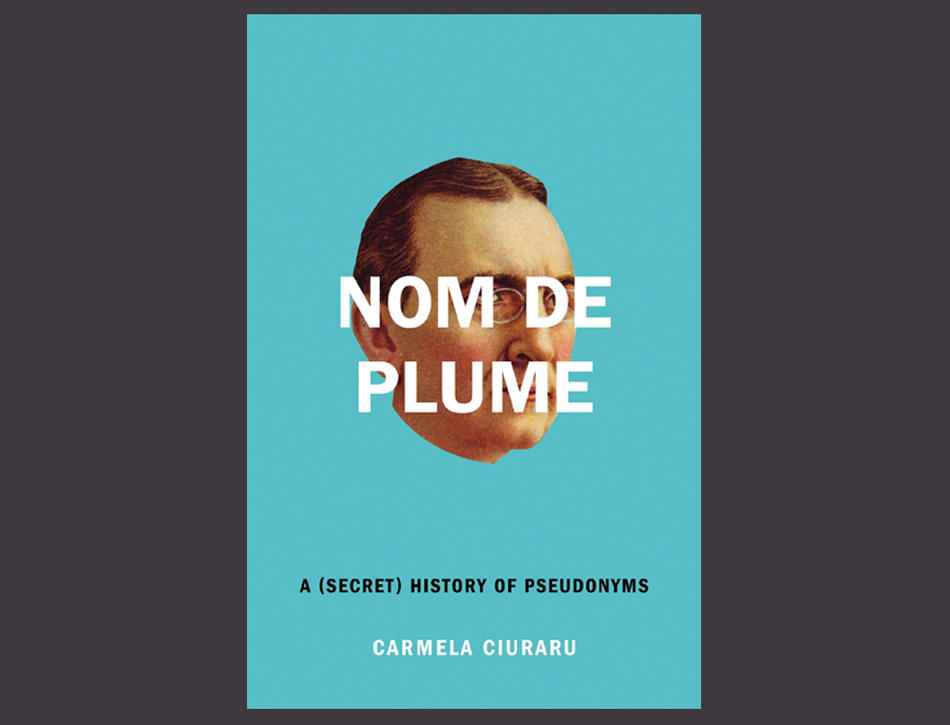

In Nom de Plume: A (Secret) History of Pseudonyms, Carmela Ciuraru (her real name) chronicles the lives of 16 notable authors who wrote under false names, and recounts the lives of the pseudonyms themselves. Samuel Clemens, for example, was born in Missouri in 1835, but Mark Twain was born in Nevada in 1863, and Ciuraru ’96JRN accounts for both their stories. Mary Ann Evans — a woman in Victorian England who not only lived with someone else’s husband, but worse, wrote novels — was exactly right in her assertion that George Eliot’s reputation was more respectable than her own.

Ciuraru doesn’t shy from the “disagreeables of reputation,” and instead presents a serious work of literary criticism that still reads in places like a literary Us Weekly. She argues that as a whole, great writers were a strange and lonely bunch, blessed with imagination, but scarred by childhood traumas, compulsions, and drinking problems, and that the pseudonym allowed them to express themselves without fear. More compelling, Ciuraru skillfully uses diary entries and letters from her subjects to illustrate how figures from Sylvia Plath to Isak Dinesen to the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa felt the presence within themselves of at least one other being. As Dinesen wrote in one of her stories, they believed that “all the people in the world ought to be, each of them, more than one, and they would all . . . be more easy at heart.” With duality in mind, the same Ciuraru who seeks a better understanding of the English canon also delights in gossipy tidbits, revealing that Charlotte Brontë (aka Currer Bell) had a “head too large for her body” and a terrible, unrequited crush on her dashing young publisher; that science fiction writer Alice Sheldon used her alter ego, James Tiptree Jr., to flirt with the women she secretly desired; and that William Sydney Porter could never make a deadline and used the name O. Henry in part to hide the fact that he began his writing career in an Ohio jail.

The underappreciated novelist Henry Green (“a stinky drunkard with brown teeth and dirty hair” whose real name was Henry Yorke) remarked that reading prose should be “a long intimacy between strangers.” While authors themselves may prefer to be known only through their work, Nom de Plume will satisfy readers who wish to deepen the relationship.