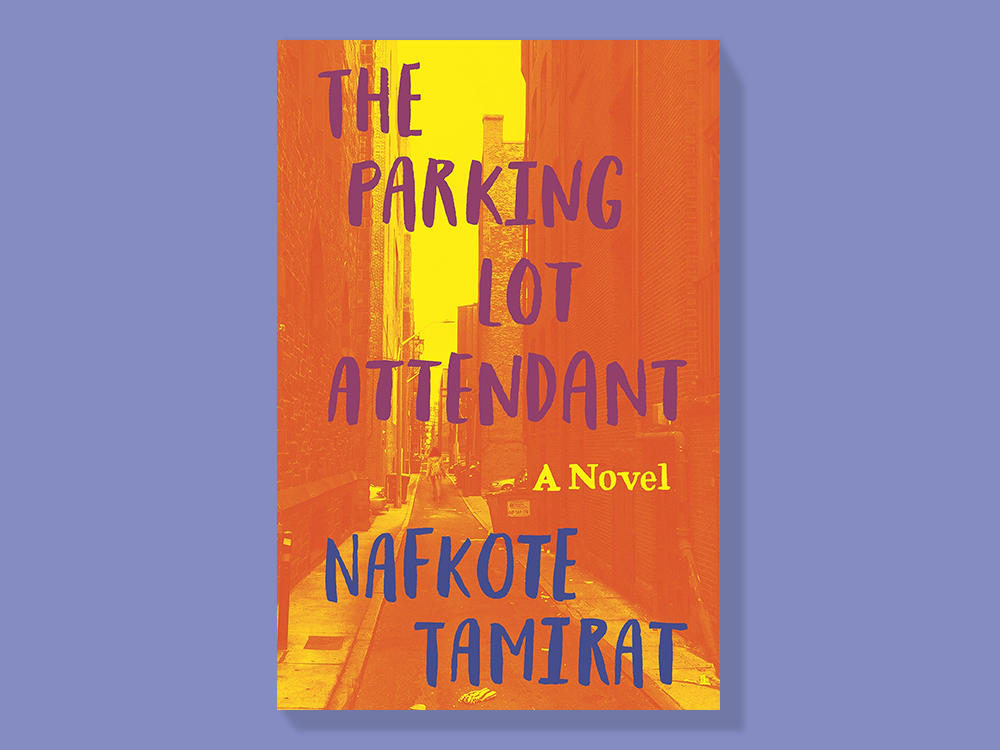

There’s not much that’s clear-cut about The Parking Lot Attendant, the inventive and often very funny debut from the young Ethiopian-American novelist Nafkote Tamirat ’13SOA. The tone is difficult to parse, and the genre is elusive — it is at once an immigrant narrative, a coming-of-age story, a dystopian fantasy, and a political thriller. But pervasive throughout are thoughtful meditations on migration, family, friendship, nationality, and what it means to belong to anyone, anywhere.

When we first meet our narrator — an unnamed teenage girl — she is living in exile with her father, the “newest and least-liked” members of a utopian colony on a remote island. Details about life on the island are vague but redolent — the constant smell of ginger in the air, the nearest phone a full day’s walk away. Her father is a handyman who is vital to the community’s survival. And yet father and daughter are not just disliked but pariahs on the island, waiting for a ruling from a mysterious council about whether they can stay. (Even in utopian communities, it seems, in this carefully drawn metaphor, the fates of desperate, displaced people are governed by arbitrary laws.)

We don’t yet know what has driven the girl and her father to the island; for that we travel back to Boston, where the girl was raised by her parents (both Ethiopian immigrants), though never at the same time. When her mother was eight months pregnant, her father abandoned the family. Six years later, he returned and her mother left. “I understood that I would never be allowed to have two parents; it would always be a relay race where the baton you had to deliver to the next person was me.”

When the narrator is fifteen, she is permitted to explore the city on her own, which leads her to Ayale, the novel’s titular parking-lot attendant and the only significant character with a name. In addition to his jurisdiction over the lot, Ayale (somewhere between thirty-five and fifty years old, with a “face this side of perfect”) unofficially presides over Boston’s Ethiopian community. The narrator stops at the lot when she overhears Ayale speaking Amharic, and he takes her under his wing, abruptly transforming her quiet life.

Quickly, the narrator joins the group of disciples ever present at the parking lot. She does her homework there and frequently accompanies Ayale for late-night sandwiches at a diner. After a while, he asks her to deliver mysterious packages to other Ethiopians around the city. For everything that seems suspicious about Ayale (and there is plenty) he has an explanation, which the narrator accepts eagerly. “I recognize that some might meet Ayale and not get swept up in his spell, might find him unkempt and horrible, especially in light of what happened later, but he remains the greatest man I’ll ever know,” she says.

What happens later, as it turns out, is the key to the narrator’s banishment; it’s also where the novel ambitiously transforms from a contemplative look at an unconventional friendship to a wild account of international crime, border disputes, and even murder.

Tamirat has named Columbia professors Donald Antrim and Victor LaValle ’98SOA as influences on her writing, and her bold experimentation with genre, particularly in the second half of the book, reflects that influence. The shift is a bit dizzying, but the underlying idea behind Ayale’s mystery is fascinating, and worth the tumultuous narrative ride. Through Ayale, Tamirat manages to subvert the narrative of colonialism, daring to imagine what would happen if the Black diaspora came together to form a new empire.