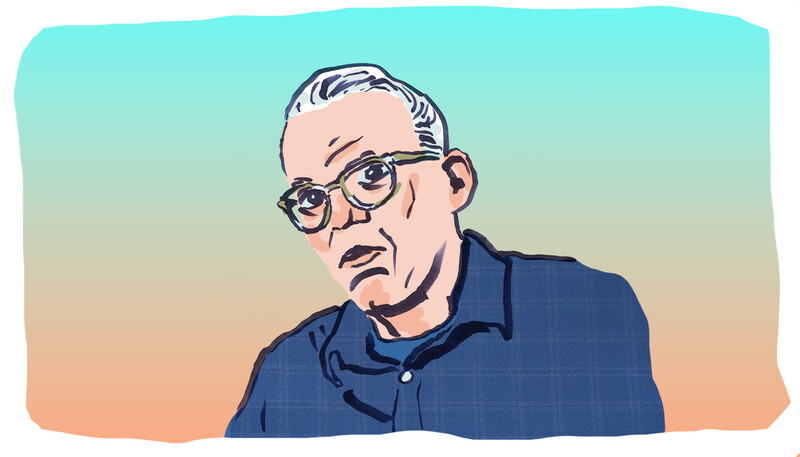

Lee Bollinger is known for his commitment to the emerging revolution in the life sciences, his substantive defense of diversity and affirmative action, and for his belief in the role of universities in promoting art and culture. The editor of Columbia Magazine talked with him recently about more general topics—from preserving the intellectual atmosphere of the University to the challenge of finding time to write.

How does an incoming president go about acquainting himself with the institution?

Well, you talk to a lot of people—in every part of the institution. You meet with as many faculty as you can to get the flavor of what’s on their minds and what’s happening intellectually. You speak to students, staff, and alumni and find out the same kind of thing and then engage the broader community from the Morningside Heights area to all of New York and beyond. It’s a time to ground yourself in the thinking going on in the institution.

The institution is in very good shape and has made enormous progress over the past twenty years. Financially as well as spiritually, the institution is alive and well. I think the thing that has impressed me the most is the dedication of people within Columbia to Columbia—and I include alumni in that. We are in a good position to move even further ahead.

You mention the spiritual condition of the University. How do you measure that?

You know when you’re around people who are bored or simply going through the motions of their responsibilities. And you know when the opposite is true, when people feel a tremendous sense of excitement at being part of a group, part of an organization. I just spoke to a person this morning who has been a member of the faculty for many years and who has been an academic administrator, and he said that he finds it an astonishing university. And I hear that word—astonishing—repeated frequently, with a genuine underlying conviction that I believe and respect.

Looking back on your accomplishments at Michigan, what would you say you’re most proud of?

Three things: The emphasis on life sciences and the effort to help the institution become a participant in the incredibly exciting discoveries that are happening in that area of knowledge—that would be one of the first. A second would be the effort to enrich the arts and culture on campus and the surrounding region. The third—not that I’d rank them in this order—would be the effort to defend affirmative action and diversity as is consistent with a great university’s mission.

Newsweek placed you among “a new breed of visionary leaders who are more willing and able to take risky stands on issues that they believe in.” Do you consider that role a calling?

I wouldn’t characterize it in that way. I do believe that university presidents have a responsibility to address the issues of their time, but I especially believe that when there are issues directly involving universities, it’s critical that we speak to the broader society about those issues and the values that are at stake and that we do so in a way that is understandable.

Private and public universities play a very special role in American society. They are highly regarded and very well supported through a variety of sources. So when an issue arises in this society that concerns university policies or actions, it is a very great responsibility on our part to respond. I don’t think that university presidents should go looking for issues to speak to, but if we have expertise, if we have a basis for a public discussion, I think we should participate.

You’ve said that preserving the intellectual atmosphere of universities is one of the most important issues. What do you mean by that?

I mean several things by that. I think that universities are created around a difficult-to-define, but nevertheless very real, way of thinking that is different from the ways of thinking beyond the university. We have various terms that begin to get at this: a kind of open-mindedness, a tolerance, an attitude of exploration of ideas, a skepticism, a seeking for truth. We can identify a number of facets of this intellectual character, but I don’t think any one of them or even most of them put together fully capture what’s involved.

I do think that when you are part of an academic community you are engaged in a different way of thinking—not only thinking about different things, but thinking about them differently. It’s extremely important for society to have these protected spheres where this kind of openness and attitude of exploration prevail. And it’s a wonderful contrast to the ways of thinking that occur outside of the community, which are productive in their own spheres. These ways of thinking exist in some tension, one not fully comfortable with the other. The thought patterns in the political world don’t work very well in the academic community, and the thought patterns in the academic world don’t work very well in the political arena. That’s also true when the commercial world comes into contact—as it should, as it must—with the academic world. Sometimes that breeds suspicion on one side toward the other. Trying continuously to preserve the ways of thinking that are right for each sphere, I think, is what’s called for.

A lot of people would say that Columbia does a better job than most universities in providing this intellectual atmosphere.

I agree that Columbia has an approach to this that is quite distinctive and special. To me, given my general orientation to intellectual life, I think it’s the best possible way of thinking about learning.

At Columbia College, of course, that approach is the Core Curriculum. All you have to do is spend some time reading Aristotle’s Ethics, or an essay by Montaigne or any of the works that we would classify as the great books of our history, and you realize how active your mind suddenly becomes. You are in the presence of a discussion that fully takes you out of the ordinary experience and moves you into a different realm of thinking.

And it’s no wonder that generation after generation of people return to these great works and find them so engaging. One doesn’t read them simply for enlightenment but also for a sense of moving to an entirely different plane of observation about the world. You suddenly become a participant in a centuries-old discussion about things that matter enormously. So much of life is built on routine, and that’s understandable. Routine is very much a means of getting through every day as an individual, as an organization, as a society. But routines are built on simplicities and the acceptance of tacit assumptions, and these great works do not operate in those ways. They immediately give you a perspective on things that lead you to think broadly and differently. Now that’s what we immerse students in. That’s what I believe living in a great university means.

More and more, Columbia has been encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration throughout the University. Is that still high on the agenda here?

It has to be high on the agenda here; it has to be high at any university. I have the highest regard for the working reality of division of labor, expertise, and specialization. It has brought enormous assets to the world. But it’s also important to recognize that specialization can become so deep that it cuts off access to other things that we should know.

But there is a still more profound issue: As you dig deeper in some fields—in many fields, perhaps—we find that divisions actually begin to disappear. What began as boundaries between things to think about or ways of thinking eventually dissolve. Only by bringing people together will we realize that.

Why do you continue to teach?

I’ll be teaching an undergraduate course on freedom of speech and press to a couple of hundred students. There are several reasons for teaching. One is that I am at base a scholar and a teacher, and I continue to want to do both. It is to me one of the best lives possible: to learn about an area of the world—in my case, freedom of speech and press—to think about it, contribute to the ways in which other people think about the subject, and then to teach and initiate students in the field. It’s what I began doing and what I love to do, and I don’t want to give it up.

And the second reason is that teaching is the best way I know to stay in touch emotionally—and physically, for that matter—with what faculty and students are doing. It’s very possible, I should add, to become removed—not deliberately, but just naturally— from the very life of the University. It is possible to be in meeting after meeting, even with faculty and students, and end up having too little idea of what is going on in your institution. And the third reason is that when the day comes that I am no longer president, I want to be ready to return to teaching and research.

You’re working on a book. What is it about?

It’s a general project that has been a part of my work for many years now: trying to understand the role of what we might call public cultural institutions in this society—public and private universities, public broadcasting, museums, the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, libraries—institutions that have at their core a set of purposes that are regarded as special and distinctive in society, having to do with the preservation of knowledge and the perpetuation of culture as we know it.

But I think most of all they are concerned with preserving a distinctive way of thinking about the world, and there are three main issues that have arisen with respect to these institutions in the past several years. One is: Why should there be public support of cultural institutions, public and private? That’s one issue. A second is: Assuming there should be some public support, should there be recognition of some autonomy for these institutions from state control as a matter of constitutional principle and policy? Just because the state funds universities, should that entitle it to condition that funding on any policy it chooses? The third issue is internal. We all say that it is bad for universities to be “politicized.” What do we mean by that? When have we crossed the boundary and allowed political culture to dominate?

In order to answer any one of those three issues or all of them, you have to have a general theory of what these institutions do in society. Why should the public support them? Why should they have autonomy? And what is the character that needs to be preserved within them?

There have been, of course, specific controversies about this: the Mapplethorpe issue with respect to the NEA is an example, and I could name many others—but I think it’s that collection of issues and that desire to have a theory that has been my principle concern.

How do you find time to work on your book?

You try to fill in the cracks of the day with your thinking. There are far too many meetings in life, and you can actually get a lot more work done by having fewer of them, so I try not to fill up my day with large meetings. And if you’re interested in something, you find that you can’t really get it out of your mind and don’t want to get it out of your mind, and so there are really many minutes and even hours over the course of the weeks and months in which ideas can revolve around in your mind and you can make some progress.

When it comes time actually to write, then you need to set aside some concentrated time, and I try to do that when necessary. In the case of lectures or a paper, that’s certainly manageable. There’s no doubt that it is harder in the context of a book.

Is it true that you were until recently a competitive sprinter?

Yes, although it’s receding more quickly than I would like. “Recently,” fortunately, is an ambiguous word, so I can agree with it without having to say how many months or years.

As Lee Bollinger begins his Columbia marathon, we look forward to checking in with him regularly along the way.