It has musty top notes, a hint of almond, and a leathery finish.

A terrible wine? Not exactly. It’s the scent of an 1820 edition of Cervantes’s Don Quixote owned by the Morgan Library and Museum in Murray Hill, Manhattan.

Jorge Otero-Pailos, a Columbia professor of historic preservation, was savoring the book’s almost nutty aroma on a recent Monday morning while leading a first-of-its-kind olfactory investigation of the library. He and seven graduate students in his Experimental Preservation course were attempting to describe, and ultimately recreate and preserve, an array of odors that drift about the lavishly decorated neoclassical building that financier J. P. Morgan (1837–1913) built to house his massive collection of rare books and art.

“Smell is such a powerful component of how we experience physical spaces,” says Otero-Pailos, who directs the historic preservation program at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation. “So why shouldn’t we try to document the scents that occupy important buildings?”

Otero-Pailos began the collaboration with the Morgan Library after meeting a curator there, Christine Nelson ’90LS, who shared his interest in chronicling historic odors. Nelson had witnessed the powerful effect that smells can have on people; visitors to the Morgan frequently told her that the scents of its books evoked for them cherished memories of times spent in libraries as students. This made Nelson wonder if the Morgan’s redolence could be used to deepen people’s interest in the building’s history.

“Could we go beyond the romance of the ‘old-book smell’ and investigate the many scents that contributed to the building’s presence in J. P. Morgan’s day?” she says. “Could a focus on historic smells somehow illuminate the human stories associated with the building?”

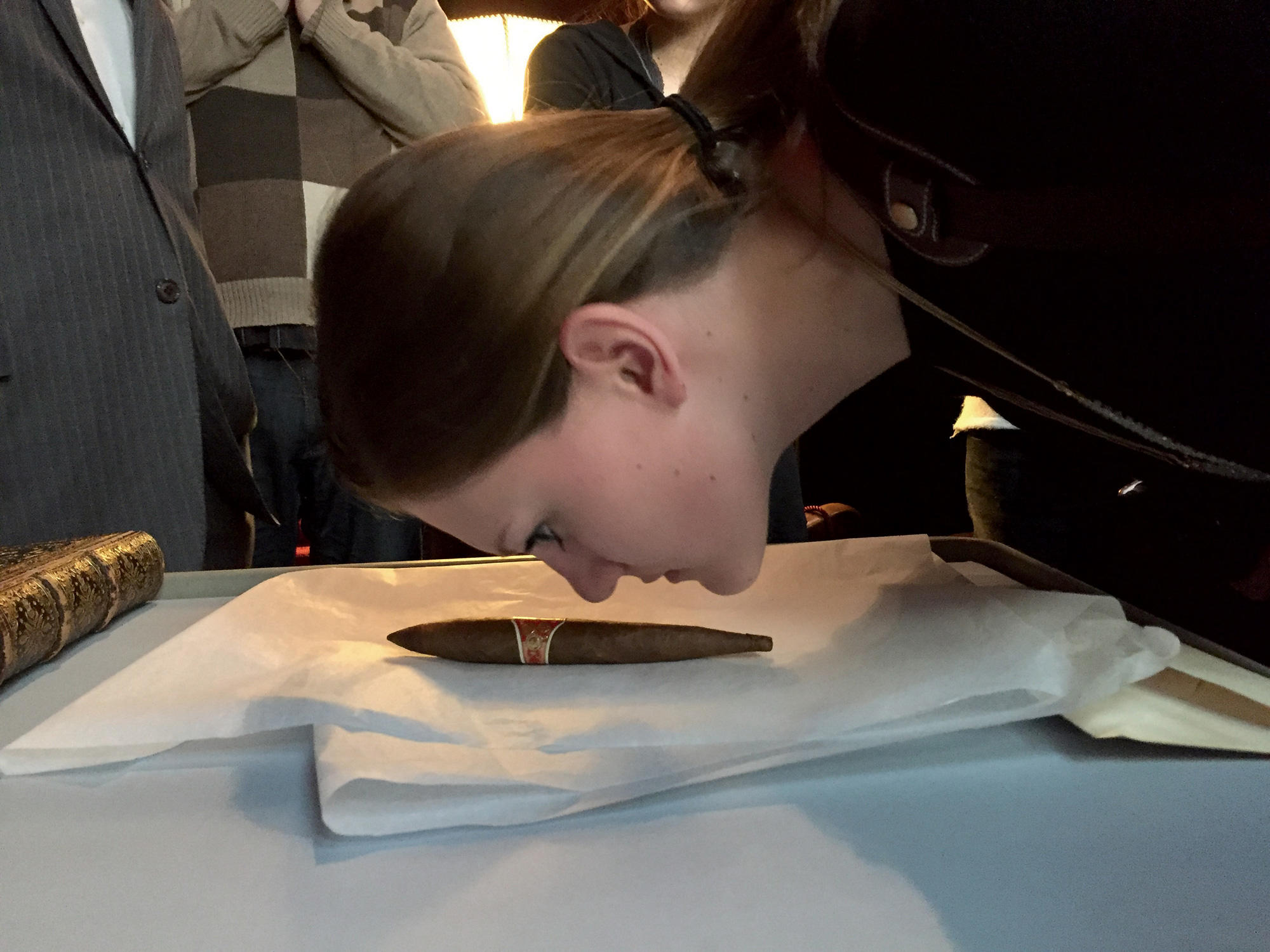

To help Nelson answer those questions, Otero-Pailos and his students made several trips to the Morgan, toting a bell-shaped device that sucks molecules off the surface of objects and converts them into a form that can be chemically analyzed in a laboratory. Using this contraption, the students collected the odors wafting off dozens of books, paintings, furniture pieces, tapestries, carpets, and relics — including a box of J. P. Morgan’s favorite Cuban cigars. They then sent the samples to the Manhattan lab of International Flavors and Fragrances (IFF), a company that creates smells for perfume makers. A few weeks later, a team of IFF chemists led by master perfumer Carlos Benaim sent the researchers several boxes of blue vials containing liquefied versions of all the scents they had collected.

“One of the things we discovered is that even relatively simple smells, like the sweet floral scent of a cigar, contain many distinct chemical notes,” says Justin Miles Clevenger, a student of historic preservation who participated in the project. “Smell is surprisingly complicated.”

The Columbia students have proposed a number of ways the Morgan could utilize their bottled-up bouquets to enhance visitors’ experiences. In addition to providing people an opportunity to enjoy the aromas of books that are too old to be handled routinely, they suggested that special scent-based exhibitions could recreate the ambiance of important moments in the library’s history. A potpourri of cologne, sweat, and cigar smoke could help conjure the infamous night in 1907 when J. P. Morgan locked more than one hundred prominent bankers in his study to persuade them to find a solution to an impending financial crisis. The presentation of Morgan’s own casket at the site in 1913 might demand a whiff of five thousand particularly pungent Jacqueminot roses barely masking bottom notes of formaldehyde.

Nelson says the Morgan Library is now considering the students’ ideas, possibly to be showcased in a sensory gallery.

According to Otero-Pailos, the experiment was especially valuable to his students, as it helped them to see the creativity that can go into historic preservation.

“What I try to show students is that reservation can be a dynamic, imaginative endeavor,” he says. “On the one hand, you are documenting and protecting what exists at a historic site. But you can also take the next step, which is to find ways of bringing the past alive for people, to give them new experiences, and to create new cultural meaning.”