Nainoa (Noa) Flores is seven years old when his family takes a boat tour in their native Hawaii — a common activity for tourists, but a rare treat for working-class locals like them. Then something remarkable happens that will change the family forever: Noa falls overboard into shark-infested waters. But instead of mauling him, the sharks carry Noa gently in their mouths, returning him to the boat unharmed. “And this,” says Noa’s mother, Malia, “was when I started to believe.”

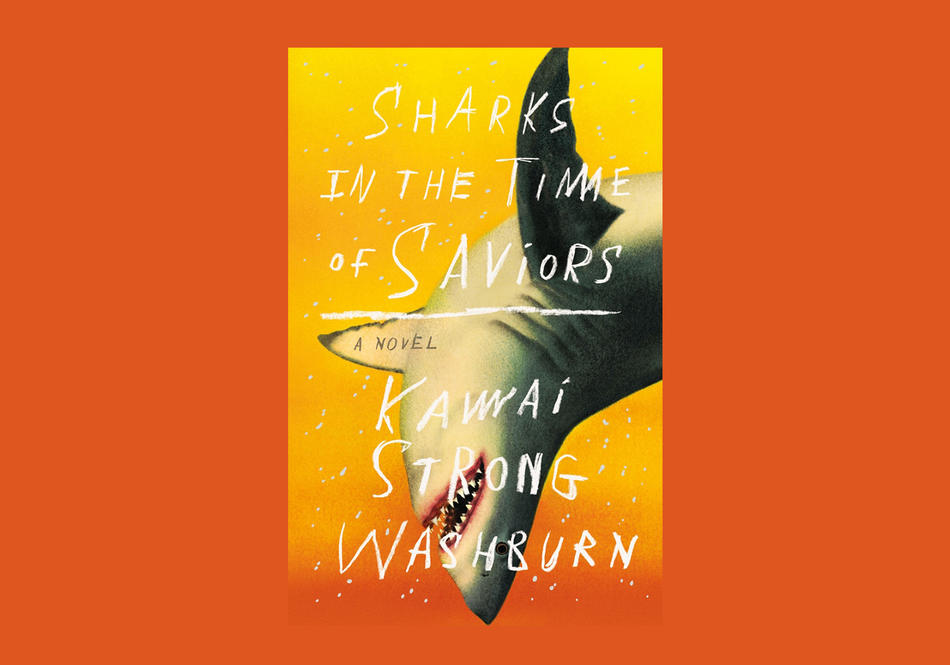

Malia — the matriarch of the family that Kawai Strong Washburn ’08SIPA conjures in his standout debut novel, Sharks in the Time of Saviors — is desperate for something to put her faith in. She and her husband have recently moved the family from the Big Island, where they worked as laborers on a sugarcane plantation, to Oahu, and they are drowning in debt. Noa’s rescue is miraculous not only because his life is spared but because it echoes an ancient Hawaiian legend that Malia remembers from her childhood — one that suggests that Noa, now anointed, will be the savior of his family, perhaps even of his people. Initially that prophecy seems to come true when Noa’s touch appears to heal a friend’s wound after an accident. Soon the entire community is waiting to see the “miracle boy,” hoping that he’ll cure their ailments. For the Flores family, Noa’s blessing is the windfall they need: the people who come to see Noa will pay.

But it’s also clear that the miracle will exact a price. Noa’s siblings, despite significant talents of their own — his older brother, Dean, is an exceptional basketball player and his younger sister, Kaui, an accomplished student — grow up bitter in his shadow. Noa, who never asked for his gift, begins to buckle under the burden of supporting his family’s finances and his community’s health. And when his gift wavers, he wonders if it was ever there at all or just a story the family told themselves.

Though the ancient legend provides the backbone of the book, Washburn expertly fits it into a very modern story, full of its own kind of myths. For the Flores family, there is the myth of the mainland: the idea that opportunity is just an ocean away. “I’m going to take us all away from this,” Dean thinks. “I’m gonna make it so that can’t no one order us around for anything.” Amazingly, they do all make it to that promised land — Noa gets a scholarship to Stanford, Dean an offer to play college basketball in Spokane, and Kaui an opportunity to study science in San Diego — but of course their demons follow them off the plane. And with the family fractured, strewn across the West Coast, their struggles seem to intensify. When tragedy strikes, in a beautifully drawn but utterly heart-wrenching sequence of events, they find themselves banding together again, drawn to their homeland as if by a magnet.

But perhaps the most central myth of the novel is that of Hawaii itself. In the American imagination, Hawaii is synonymous with vacation, a paradise put on earth specifically to serve as a respite from real life. Without seeming preachy, Washburn — a native of Hawaii’s Big Island who now lives on the mainland — firmly lays that idea to rest. The author makes it clear that Hawaii is full of the same real life that tourists (disparagingly called haoles, or foreigners) are trying to escape: unpaid bills, mental illness, addiction, hunger, homelessness, squandered opportunities. Native Hawaiians are caught in a painful paradox, now utterly dependent for survival on the tourism that stole their homeland. “The kingdom of Hawai‘i had long been broken — the breathing rain forests and singing green reefs crushed under the haole fists of beach resorts and skyscrapers.”

Both the New York Times and Oprah have heralded Washburn as an exciting new literary voice, and with good reason. A passionate climate activist, Washburn imbues his writing with an ardent respect for his native land and a clear warning about the dangers of treating it, as mainland America has done for a century, like a theme park. His prose is as lush as the islands that he writes about, and he uses it to create an opus that is both deeply specific to Hawaii and full of universal themes — the tensions between magic and reality, expectation and disappointment, and, perhaps most importantly, exile and home.