In a small, tidy living room in a retirement village a few miles inland from Avon-by-the-Sea, New Jersey, Robert Giroux '36CC sits with his old friend Charlie Reilly. The two men, both in their nineties, have known each other since grammar school in Jersey City, and are now next-door neighbors. Occasionally, Charlie drops by to visit.

"Tell him the story, Bob," Charlie says.

As the editor, publisher, and longtime chairman of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Bob has lots of stories. They're his stock-in-trade.

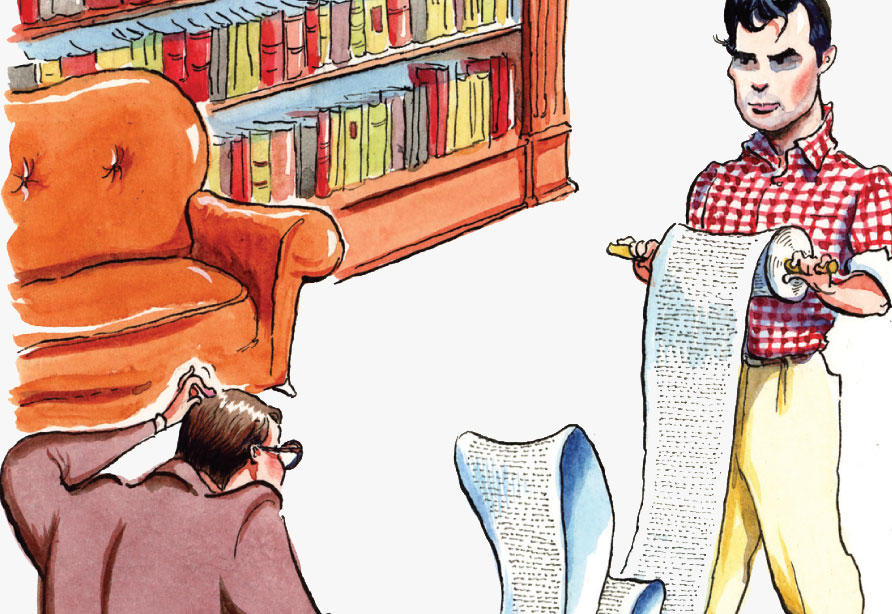

"Tell him," says Charlie, "how he came in with a scroll of paper."

Giroux nods once at Charlie's exhortation, his pale, clear eyes open wide in a sturdy head crowned with wisps of silk white hair. Behind him is a modest bookcase with glass doors, and on the wall by the kitchen hangs a photograph of a young Elizabeth Bishop.

"He had typed his novel on a scroll of paper," Giroux begins. His voice is deep, and he drops his Rs with old New York gusto — "paper" is papuh, "Bernard" is Bernahd. "And then he brought it over to my office — this big roll of paper."

The scribe in question was former Columbia football player Jack Kerouac, and the composition, single-spaced and 120 feet long, was On the Road, which turned 50 in September. Giroux, who while at Harcourt Brace had published Kerouac's first major work, The Town and the City, in 1950, was uncertain what to make of "the roll," as Kerouac called it. Nor was he certain what to make of the 29-year-old Kerouac, who was in a strange, excitable mood and clearly expected his editor to give his blessing. But Giroux couldn't get past the logistical problems of publishing the work in scroll form.

"It was my mistake," he says. "I was just being practical. I said, "You can't publish a book typed on a roll of paper." And he said, "It will be published, because it was written by the Holy Ghost. He was either drunk or on drugs, I don't know what. Anyway, he left me in disgust."

Typed in three Benzedrine-powered weeks in April 1951 from notebooks Kerouac kept during his cross-country travels, the novel later found a home at Viking, which published it, after extensive edits, in 1957. That same year, Giroux, keeping pace artistically if not cosmically, came out with The Assistant by Bernard Malamud. On the Road, of course, went on to become a cultural touchstone, and to date has sold over 5 million copies worldwide.

If Giroux had missed Kerouac's drift and let a big one get away, his lineup of poets and writers was still the Murderers Row of the New York publishing world. There was Flannery O'Connor ("she had a wonderful, suppressed sense of humor, and I loved to hear her talk"), Robert Lowell, Lowell's wife Jean Stafford ("one of the best prose writers that I edited; she got better and better, and if she would have lived we'd still be talking about her today"), Malamud, George Orwell ("one of my favorites — a devotee of honesty in writing"), John Berryman '38CC, whom Giroux had published in the Columbia Review where he was editor in chief, and Nobel laureate T. S. Eliot, who, when Giroux was hired away from Harcourt by Roger Straus in 1955, called Giroux and said, "I'm coming with you." O'Connor followed, too, as did Malamud, Lowell, Berryman, and 13 others. It was the most significant migration of writers from one house to another that the industry had ever seen.

In 1965, Giroux was made partner in the firm, which became Farrar, Straus and Giroux, establishing Giroux in the pantheon of Columbia-bred publishers that included Alfred Harcourt, Donald Brace, Richard Simon, Max Schuster, George Delacorte, Ian Ballantine, Bennett Cerf (Random House), and Alfred A. Knopf.

"I was always interested in real writers," Giroux says. "By that I mean people who were not just writing a novel, or a terrific book of some kind, but who were just going to write."

That might sound extravagantly idealistic in such a market-driven business, but publishing was essentially the same number-crunching affair in 1957 that it is today. A missed opportunity like On the Road — whose anniversary is being marked by Viking's first-ever publication of the ur-scroll that Giroux passed up — comes at a steep price for publishers and readers alike. As literary agent Morton Janklow '53LAW told Columbia Magazine in 1991, "the profits from the big books fund the risks on the little books." One On the Road can give birth to a dozen potential literary masterpieces.

But Giroux, as it happened, had already struck gold by the time Kerouac came by to unfurl his megillah. Three years earlier, in 1948, Giroux, while still at Harcourt, published a book by another Columbia Review confederate, Thomas Merton '38CC.

Merton's book, The Seven Storey Mountain, an autobiography about Merton's conversion to Roman Catholicism and his life as a Trappist monk, sold over 600,000 copies in the original hardcover, and more than a million in paperback. And, like On the Road, it has never been out of print.

"The Seven Storey Mountain was, I guess, the biggest best seller of my career," says Giroux. "I was never one for trotting out sales, but that was a big one."

Charlie Reilly concurs. "Yes, it was, Bob," he says, nodding. "Yes, it was."