On October 11, 1975, as the clocks of New York struck 11:30 p.m., a new show debuted on NBC. Produced by Lorne Michaels and featuring a ragtag cast of sketch-comedy guerrillas with no television experience, NBC’s Saturday Night (the Live would come later) was a flaming comic canister tossed into the yawning darkness of late-night weekend programming — the network’s attempt to snag the elusive and coveted 18–34 demographic.

Doug Hill ’76JRN, a Kansas-born child of the television age, was pretty much the target audience. At twenty-five, he had been to college on the West Coast, wrapped himself in the counterculture, and arrived at Columbia Journalism School with a lot of talent and little direction. He did not watch the first SNL episode that October night (few did). Probably he was downtown at CBGB, the music club that became the subject of his J-school thesis. “I had nothing but contempt for TV,” Hill says. “I didn’t even own a set.”

And yet, after graduating, Hill found work writing for the TV journal Broadcasting. That’s how he met Jeff Weingrad, a writer who had covered SNL. Hill and Weingrad became friends, and in 1983, with SNL still running and Michaels’s number still in Weingrad’s Rolodex, they had an idea to cowrite a history of the show, which, by virtue of the stars it had launched (Chevy Chase, John Belushi, Bill Murray, Eddie Murphy) and the cultural currency it supplied (the Coneheads, the Blues Brothers, noogies), was already an institution.

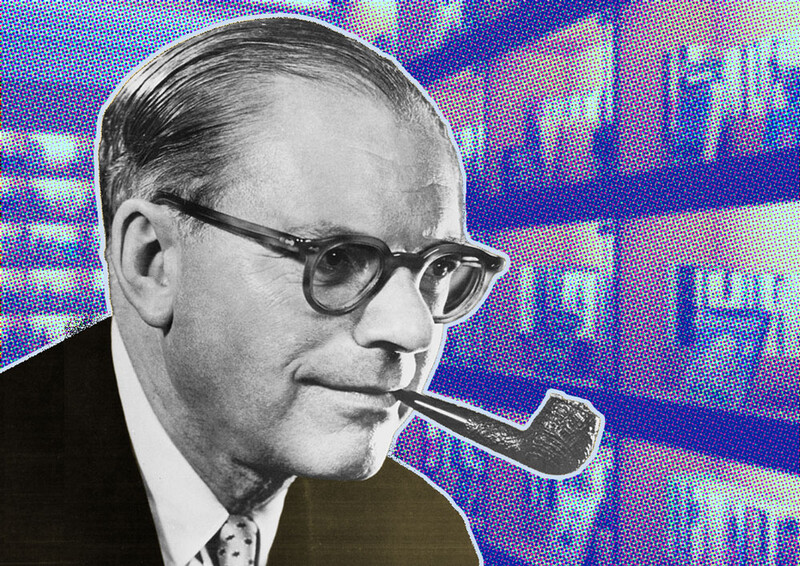

“We went to Lorne with our proposal, and he said yes,” says Hill. “That opened all the doors for us.” Over the next two years, the pair interviewed more than two hundred people, from the top brass at NBC to the show’s directors, production staff, and writers (Al Franken and Tom Davis were especially helpful). Just two of the original cast members, Chase and Laraine Newman, agreed to talk — Belushi had died in 1982, and the others had left the show in recent years and were still recovering from it. But the authors gathered a mountain of untapped material, and from it they fashioned a kind of bible of the show’s first decade: its genesis (NBC president Herb Schlosser wrote a memo in early 1975 outlining the idea for a live late-night weekend show); exoduses (a burned-out Michaels left in 1980, followed by the entire cast, though he would return five years later); and revelations (read the book).

Hill and Weingrad divided the workload: they both conducted research, and then Hill wrote and Weingrad edited. The finished product, titled Saturday Night: A Backstage History of Saturday Night Live, was published in 1986 — a smart, compelling, richly detailed page-turner about, as the authors write, “highly creative and consciously eccentric people” who were operating in a pressure cooker of fast fame, drugs, and old-guard network politics.

Critics adored the book, but among SNL insiders, opinions varied. Michaels questioned the veracity of certain anecdotes, and Chevy Chase expressed a wish to meet the authors in a dark alley with a pair of pruning shears. At 30 Rockefeller Center, from which SNL airs, NBC’s then president Brandon Tartikoff and others praised the book, and the AP’s verdict that it “may be the best book ever written about television” has proved as durable as the show. Last year, Histria Books published a new edition to mark SNL’s fiftieth anniversary.

After the 1986 publication, Hill mostly unplugged from SNL. He spent ten years writing for TV Guide, then, as he describes it, “kind of wandered off into the wilderness.” He got hooked on the French philosopher Jacques Ellul’s writings on technology and society, and in 2016 the University of Georgia Press published Hill’s second book, Not So Fast: Thinking Twice About Technology. Now he is finishing a book on the life and thought of Max Weber.

Hill intermittently checks in on SNL — his favorite performers have been Phil Hartman and Tina Fey — and he credits the show’s success to its authenticity. More than anything before it, he says, SNL, in its attitude and its chaos, reflected reality.

“All the time I was growing up, television was telling lies,” he says. “We had Ozzie and Harriet and Leave It to Beaver, and they just weren’t honest. Saturday Night Live came on and told the truth.”

This article appears in the Fall 2025 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Saturday Night Dive."