In Ian McEwan’s novel Atonement, a thirteen-year-old girl in prewar England makes a terrible mistake. Led astray by a head full of melodramatic stories, Briony Tallis callously breaks up a romantic relationship, creating a rift that opens into a chasm, leaving two lives ruined and her own eclipsed by guilt.

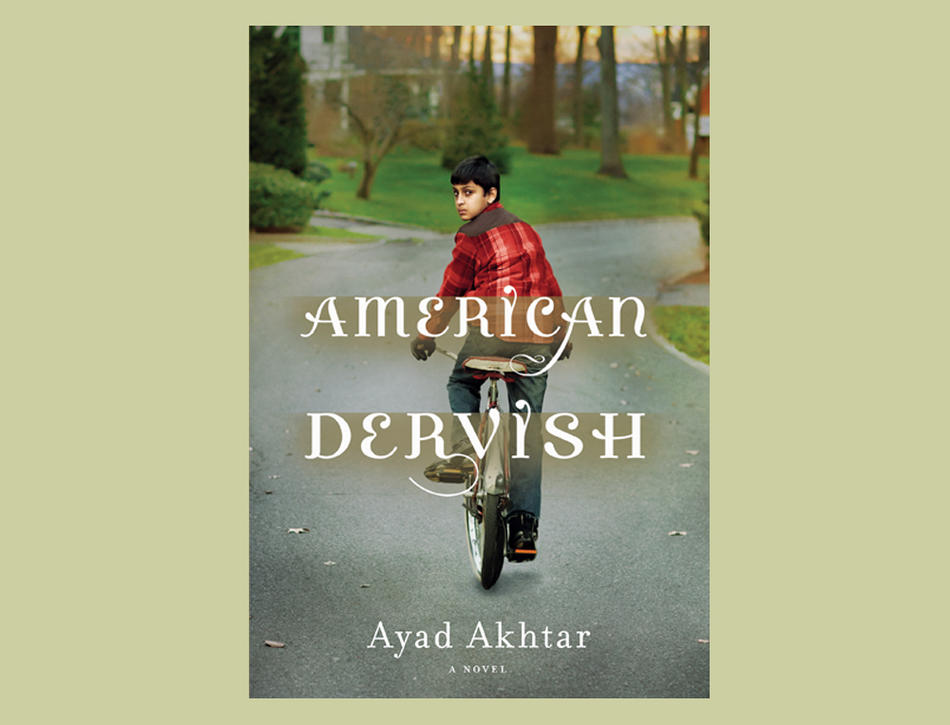

Had Atonement been set in suburban Milwaukee, circa 1981, and had Briony been a Pakistani-American boy, she’d have been a dead ringer for Hayat Shah, the narrator of American Dervish, the much-anticipated debut novel from Ayad Akhtar ’03SOA. Like Briony, Hayat is responsible for the demise of an important relationship and the tragic chain of events that follows it. But while Briony is inspired by fiction, the voice in Hayat’s head — his moral compass — is Muslim fundamentalism.

Hayat doesn’t start out as a zealot. The only child of educated, secular parents, he sees Islam as a minor inconvenience, something that excludes him from the church ice-cream social and the school cafeteria line on hot-dog days. His father, Naveed, a philandering doctor who hides liquor bottles in his car, is firmly opposed to religion, while his mother, Muneer, is more improvisational. She adheres strictly to some traditions but also exercises her own spiritual whim, pulling Hayat out of school on Yom Kippur, for example, having been touched by the holiday’s spirit of repentance and forgiveness. If Muneer, who trained as a Freudian psychologist but was forced to give up her career for marriage, has a parenting goal, it is not that Hayat grow up to be a pious man but, rather, simply a good one, particularly where women are concerned: “When a Muslim woman is too smart, she pays the price for it ... in abuse,” she warns, dramatically. “That’s why I’m bringing you up differently, so that you learn how to respect a woman.”

Then, suddenly, there is a woman: Muneer’s best friend, Mina, who flees a dismal marriage in Pakistan and comes with her four-year-old son to live with the Shahs. Eleven-year-old Hayat is wary, but Mina turns out to be the stuff of preadolescent fantasy — breathtakingly beautiful, with just enough charm and confidence to give him hope (“She smiled and I was struck,” he says when they pick her up at the airport, paving the way for an onslaught of coming-of-age clichés).

Soon, Mina is inviting Hayat to her room for nightly stories from the Koran, against his father’s will. Mina is relatively secular, too, with no headscarf and an eye toward a career as a beauty technician, but she has a devotion to the Koran that is intellectual, almost artistic. For her, Allah is a benevolent, peaceful source. “Allah will always forgive you, no matter what you do,” she reminds Hayat.

With Mina’s encouragement, Hayat begins not just to study the Koran but to memorize it, the first step toward becoming a scholar, or hafiz. Sexual and spiritual development merge in awkward, confusing, and thrilling ways, and Hayat becomes charged with feelings: “That night my nerve ends teemed and pulsed,” he says, after Mina gives him his own Koran. “I still recall the vividness of my cotton pajamas against my arms and legs, the fabric pressing here and there, distinct points of contact alive with pleasure ... I fell asleep and dreamt all night of Mina’s hands turning the yellow-white pages of my new Quran.”

But Mina is oblivious to Hayat’s interest, finding favor instead with Naveed’s brilliant young research partner, Nathan Wolfsohn (“Jewish, urbane, and pleasantly gregarious”). He and Mina meet at a family barbecue and are instantly smitten, leading to a heavily chaperoned courtship. Both Naveed and Muneer encourage the relationship, especially when Nathan makes an enormous sacrifice: despite having lost much of his family to the Holocaust, he offers to convert to Islam. As the relationship escalates, though, so do the hateful attacks against it from Muslim extremists. The Shahs cannot shelter Mina and Nathan from the community. “My father warned me about this,” Nathan despairs. “He’s said his whole life that no matter who we try to be, no matter who we become, we’re always Jews.” Nor can they silence their own son, who has been listening a little more closely than anyone thought.

Akhtar studied film, not fiction writing, at Columbia, and his plotting is more impressive than his prose, which borders on the overwrought. But in many ways his experience in film ideally prepared him for writing this book: while still in graduate school, Akhtar developed the idea for The War Within, a film in which he eventually starred, about a Pakistani student’s radicalization and journey toward terrorism. Things don’t escalate that far for Hayat, though the idea that they could, that they might have in another time, is haunting. Twenty years before September 11, tensions were already ripe between some Muslims and the West, and Akhtar spells them out boldly and clearly. Several novels have already been set in the aftermath of the 2001 terrorist attacks; Akhtar’s choice to look back instead at some of the forces that shaped that day is fresh and illuminating.

What most distinguishes Akhtar’s novel from its peers, though, are the complicated people that he creates to wrestle with these tensions. Akhtar’s characters are laudably three-dimensional: hypocritical, sanctimonious, confused, and also deeply sympathetic. Mina and Muneer are hardly the picture of submission, and yet we come to understand the ways in which it is important to them to be Muslim women. Naveed is a wretched husband but a devoted father and friend, and his righteous indignation at his own religion’s potential for bigotry is heart-swelling. And Hayat, at the center of it all, is not a terrorist; he is a jealous boy, a young, foolish Briony Tallis who, in his desperate quest to do right, shows how very easy it is to do wrong.