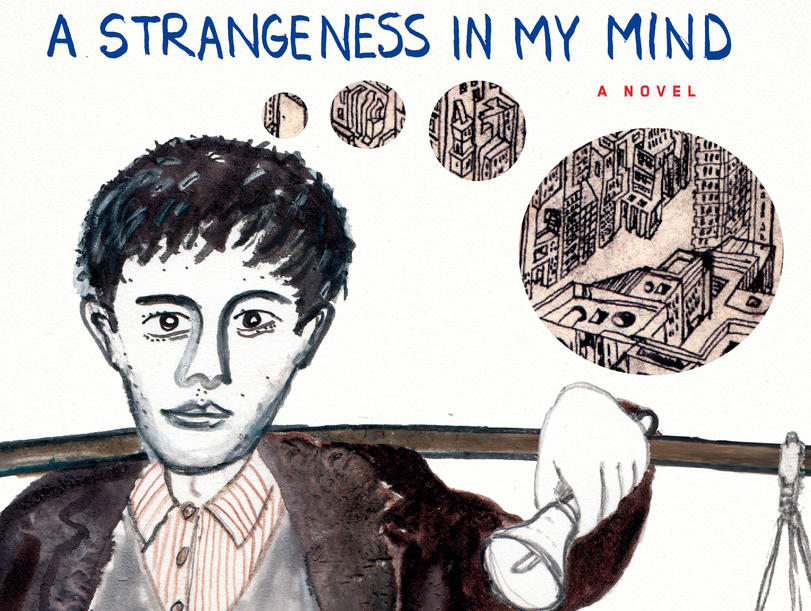

On the very last page of A Strangeness in My Mind, the latest novel by Columbia humanities professor and Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk, there is a photograph of a traditional Turkish boza seller. The slight man faces away from the camera, a long stick balanced across his shoulders. Hanging from the ends of the stick are two containers filled with his product — a traditional, mildly alcoholic drink served with cinnamon and chickpeas. Opposite him, three men squat in a doorway. A woman approaches from the left, her head covered in a scarf. The street is cobblestone, the door of the building ornate. The picture, which is undated, could be from any year in the past century, save for the graffiti of arrow-pierced hearts spray-painted on the building, marking it as relatively contemporary.

Coming at the end of this quiet, subtly powerful book, the photograph echoes the themes of the preceding six hundred pages: the melding of tradition with modernity; the juxtaposition of the individual against the group; the ideal of romantic love and the reality of relations between the sexes; the primacy of the city.

Pamuk’s book follows the small, ordinary life of Mevlut, who, like the man in the photograph, walks the streets of modern Istanbul selling boza. The work is low-paying and backbreaking, filled with aggravations ranging from hostile stray dogs to condescending customers who invite Mevlut into their homes to pour them a glass, then treat him like a curiosity from a traveling museum. He may walk ten miles a night, down alleys, through cemeteries, and over hills, and peddle only a few cups of his product.

But Mevlut loves selling boza. For him, boza links Istanbul’s past with its rapidly changing present, and roaming the city on foot at night enables him to assimilate the onslaught of modernity at his own pace.

To his family and friends, Melvut seems simple to the point of stupidity. But in fact his mind is complicated terrain, as twisted and vertiginous as Istanbul’s ancient alleys. Unlike many of the less conflicted characters in the book, who have no problem saying one thing while meaning another, Mevlut strives to reconcile his thoughts and actions, to match his intentions to his deeds.

The book opens with an episode of biblical tragicomedy that makes this goal near-impossible. After glimpsing a girl with “unforgettable eyes” at a wedding, Mevlut writes her love letters for three years. His cousin arranges for him to run away with the girl, but once the plan is enacted, Mevlut realizes a switch has been made: “They had shown him the pretty sister at the wedding, and then given him the ugly sister instead. Mevlut realized he’d been tricked.” Or had he? Mevlut and his bride, Rayiha, wind up being a true love match, and enjoy a happy and satisfying life together before tragedy strikes. But even in their moments of truest communion, Mevlut is plagued by the knowledge that his love letters were intended for Rayiha’s sister, Samiha. “Mevlut knew he could have been happy only with Rayiha. God had made them for each other,” he decides, then immediately second-guesses himself. “What would have happened if I’d put ‘Samiha’ on my letters instead of ‘Rayiha’? thought Mevlut. Would Samiha have eloped with him?”

Mevlut’s personal torment comes against the backdrop of much larger political turmoil both in the region and globally. Pamuk invokes politics often — the Turkish occupation of Cyprus, the Iranian Revolution, the Tiananmen Square protests, civil war between secular Turkish intellectuals and political Islamists, the 9/11 attacks, and the arrival of Syrian refugees in Turkey. Mevlut experiments with radicalism, but mostly remains apolitical, believing that in an unstable country, his private thoughts are best left unexpressed. Pamuk expertly shows the way this political repression leads to a form of emotional self-censorship.

By the novel’s end, Istanbul has become a city of skyscrapers and parking lots, “so big and sprawling that it was impossible to drive to and from [the] neighborhoods in a day, let alone walk.” Mevlut stares out over this “unbreachable” city from behind the barrier of an apartment-tower window, dozens of stories in the air. Sealed off in this way, he feels tremendous nostalgia for the streets he used to know so intimately, yet he refuses to believe that this lost world is truly inaccessible to him. “For the moment, he refused to choose between the two realms. His public views were correct, and so were his private ones; the intentions of the heart and the intentions of words were equally important.” Just like the boza seller in the photograph on the final page, Mevlut ends the book already a token of Istanbul’s disappearing history, but, for the moment, at one with his city.