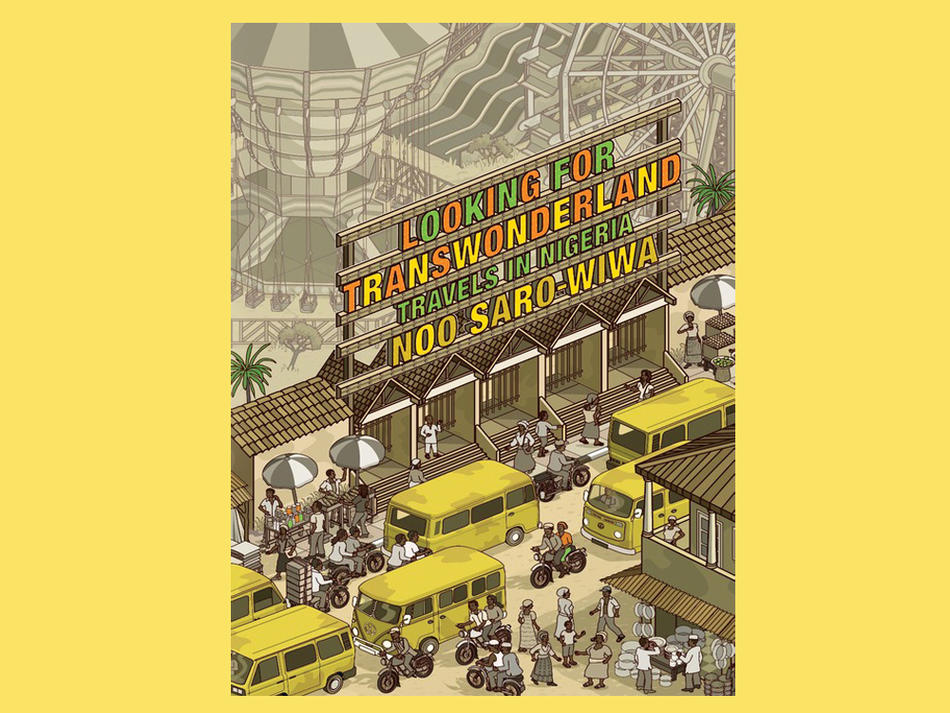

Transwonderland is an amusement park constructed, after much public anticipation, in Noo Saro-Wiwa’s native Nigeria. The park, a collection of gloriously westernized kitsch (“the closest thing Nigeria has to Disney World”), represents everything Saro-Wiwa ’01JRN felt Nigeria lacked when she was growing up in England and forced to traipse home to troublesome old Africa every summer vacation. But in Saro-Wiwa’s Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria, the park turns out to be the least of it. When she travels back to her ancestral homeland as an adult, it’s really transcendence she’s tracking. Ready or not.

Part guided tour, part family history, the journey seems to represent an important moment for the thirty-six-year-old author, an ambitious reconciliation of her past and future. Even if the parts didn’t flow together as well as they do, Saro-Wiwa’s first book would be a fresh, invigorating look at a culture not often documented in Western books — and certainly not like this.

Nigeria, it turns out, is considered by other Africans to be the rowdy child of the continent, a naughty “nation of ruffians” with a penchant for disorder that is only sometimes amusing. According to Saro-Wiwa, Nigerians “like to shout at the tops of our voices, whether we’re telling a joke, praying in church or rocking a baby to sleep.” At the theater, it seems, the only people in the audience not chatting on cell phones at an “unapologetic volume” are those yelling out unsolicited suggestions to the actors onstage. The “jagga jagga” nature of Nigerian life (the slang term, meaning “messed up,” is from a local hip-hop song a few years back) is attributable to “decades of political corruption” that have left the populace “deeply suspicious of authority.” During its forty-seven years of independence, she writes, “Nigeria has lurched from one kleptocracy to the next,” so that the photographs of national leaders on a museum wall resemble “a series of criminal mugshots, a line-up of chief suspects in the ruination of Nigeria.”

Whatever its origins, this boisterousness also speaks to a certain zest in the national character that the reader can’t help but find, at times, endearing. Best intentions in every sphere of society may be doomed to fizzle before the avalanche of “misallocated funds, apathy and ... fecklessness,” but there’s no gainsaying the fact that Nigeria was the world’s biggest importer of champagne during the oil boom of the early ’80s, and that “Nollywood” is the third-largest film industry in the world, churning out three “shoddy” and “interminable” movies per day. “It’s a money-making business,” says the author with a tone of exasperated fondness, “run largely by fast-buck entrepreneurs without a creative bone in their collective bodies.”

No wonder she uses the phrase “kissing teeth” at least a dozen times (to the sorry exclusion of other sounds/gestures) — in one instance, three on a single page. It’s a hard-to-describe sound (used in Jamaica as well as in parts of Africa) meant to express mild disapproval. The closest equivalent Westerners have is a tsk-tsk or tut-tut, but this is a hiss that can be deployed without losing one’s cool or appearing starchy.

Noo Saro-Wiwa is the daughter of slain Nigerian writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, and her travels are in part a journey to better understand his legacy. Her father was an outspoken critic of the Nigerian government. He needled officials for failing to enforce environmental regulations against widespread abuse by foreign oil interests. His arrest and execution in 1995 caused an international uproar that resulted in Nigeria’s being suspended from the Commonwealth of Nations for three and a half years. Nineteen years old at the time, Noo was forced to set aside her youthful rebelliousness and begin a long process of grasping that her father was more than just the embarrassing guy who had the bad taste to install a sea-green carpet in his home to match the stripes in the national flag. Reappraisal of her father and homeland took years, culminating in this book, which is deeply felt and also charmingly blithe.

Our guide is intrepid as she goes about balancing the dark and light of her birthplace. There seems no place she will not go and no conveyance she will not try. Weary of overcrowded buses, as well as the car driven by her father’s former chauffeur, she discovers she loves hitching rides on “okadas,” or motorcycles for hire. “Though fraught with danger and often ridden by reckless drunks in a hurry, okadas were exciting, liberating and cheap, and they appealed to a downwardly mobile side to my character I hadn’t known existed. I would use this form of transport even if I were a billionaire.”

She may be scarred by aspects of her past, but Saro-Wiwa makes sure we are well entertained as she squires us through dog shows (“The first dog, a boar bull called Razor, casually urinated during her inspection. Thoroughly amused, the crowd cheered”) and Nollywood film sets, where she is offered a role (“Once upon a time, I might have laughed at the offer. Now, I swelled with hubris ... imagining myself with a copper-coloured hair weave, preparing my Oscar acceptance speech”). Inevitably, she pays her respects to Transwonderland, a suitably “forlorn landscape of motionless machinery ... rusting amid the tall grass,” where she samples the neglected Ferris wheel. “Sitting alone on the empty ride made me feel self-conscious. Should I smile or look serious? I couldn’t decide. Smiling made me look a little foolish and deranged but keeping a straight face would make me look inappropriately solemn, if not more foolish and deranged.” A few stray onlookers look bored enough to kiss their teeth.

Saro-Wiwa is so committed to giving us a complete field dispatch, she even turns to the classified ads. Lucky thing, because her labors yield her the following, from a Sunday newspaper section where wannabe gigolos troll for sugar mamas. “Tony, 27, undergraduate, needs a caring, independent, neat and comfortable sugar mummy who needs sexual satisfaction.” “Victor from Port Harcourt needs a fat sugar mummy with big boobs. He promises to satisfy her needs.”

And here is where wheat is separated from chaff. Noo Saro-Wiwa, late of King’s College London and Columbia University, does not merely pore over these ads. Leaving no stone unturned in her quest for journalistic completeness, she phones the men that placed them.

“But can you satisfy me if you don’t find me attractive?” she sensibly asks one of her potential blind dates.

“‘Blood flows in my veins,’ he said impatiently. ‘I’m not a statue. You’re going to have feeling ... I promise.’”

Feeling is what the reader gets, too, from this daring, alert, affectionate, spunky book. You won’t need to kiss your teeth ... I promise.